Original Source: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2018/09/job-interview-questions-designer/

Tough Interview(er) Questions For The Job-Seeking Designer

Tough Interview(er) Questions For The Job-Seeking Designer

Joshua Bullock

2018-09-26T13:30:31+02:00

2018-09-26T11:46:24+00:00

Whether you’re a multi-year veteran to the UX industry or fresh out of a higher education or boot camp style program, setting out into the job market can be a daunting task for any designer. From freelancing or working for a more boutique studio, doing agency work, or joining the enterprise, a myriad of positions, requirements, and organizations are available for a design practitioner who is looking to take the next steps in their career.

In this article, I’ll present a list of questions from my personal experience to consider leading up to and even during the interview process. I’ll also include the goal when asking the questions, basically what you’re trying to learn, along with responses I’ve received when asking them of prospective employers.

As with anything, your mileage might vary, but considering these topics before an interview may help you better solidify the perspective on what you are looking for from your next position. It is written primarily from the position of an interviewee, however hiring managers may also find them valuable by looking at their company through that lens and considering them for prospective designers.

Recommended reading: The Missing Advice I Needed When Starting My Career

Understanding Design Maturity

Jared Spool and other UX leaders have written a few things about the design maturity of organizations and the ideal distribution of design resources. When considering taking a design position within an organization, how might we look at the company through this lens and better understand where they are on their experience journey? With numerous titles being thrown around (Experience Designer, Product Designer, UI Designer, Interaction Designer, UX Designer, and so on), what might provide additional clarity for the working relationship you’re about to enter into and the role you are about to assume?

Having a few years in various design roles, I’ve spent time on both sides of the interview table — both as a hiring manager and as a prospective employee. In every interview I’ve been a part of, be it part of the hiring team or as an interviewee, an opportunity was presented to inquire about the team or organization. “Do you have any questions for us?” is the most common phrase I’ve heard and this presents a golden opportunity to dig deep and gain valuable insights into the dynamics of the team and organization you’re speaking with.

Meet SmashingConf New York 2018 (Oct 23–24), focused on real challenges and real front-end solutions in the real world. From progressive web apps, Webpack and HTTP/2 to serverless, Vue.js and Nuxt — all the way to inclusive design, branding and machine learning. With Sarah Drasner, Sara Soueidan and many other speakers.

Check all topics and speakers ↬

When I am applying, I’m on the verge of entering into a new relationship, and to the best of ability, I want to understand where we are both headed. Just as the organization is investing in me as an individual, I am being asked for a commitment of time, energy, passion, creativity, and least of all artifacts. I would like to understand as much about my partners as possible. Given that no prenuptials exist in the working world, we may eventually part ways, and our engagement should be as profitable as possible for both sides.

I’ve asked the aforementioned question many times of prospective candidates, and in some cases, the response has regrettably been completely passed over. The seemingly benign, “Do you have any questions for us?” opening affords any designer a wealth of opportunity to learn more about the company and design engagement. If design solves problems by gathering information, I propose we attend the hiring process as we would any other research effort.

Interviewing is a great opportunity to get to know the company, take notes! (Large preview)

Interviewing Like A Researcher

The following is a list of questions that can assist in your evaluation of a prospective employer and provide invaluable insight into their organizational maturity in the digital product space. All of these questions can help to paint a more holistic and honest picture of the design process as well as the value that a talented designer might bring to an organization. Below I’ll share questions I’ve asked, as well as their intent, along with some responses I’ve received from prospective employers. Let’s dive in.

Question #1

“What are the three biggest challenges facing your business over the next six months? What about the six months after that?”

Why ask this?

This is on the ground information for any designer. Upcoming challenges should be readily apparent for anyone on the existing team, and they’re already considering how the person being interviewed might help solve them. Framing the question in this way can provide valuable insight into how far ahead the team is thinking and how proficient they are at planning. It also can help a designer quickly bring value and insights to the organization.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

Does work exist in the pipeline that a designer can help immediately bring to the product through evaluative research?

Is there a product that has been delayed based on initial feedback?

What insights were learned and how can that be used to tighten cycles and quickly iterate to production?

Is a project hemorrhaging funds from a past launch that didn’t grow as quickly as anticipated?

Are there ideas of how to save this investment and help it become successful?

How is this question received?

This is honestly the easiest of any question on this list. It’s a bit of a softball as I would expect any executive, manager, or team member to have this information top-of-mind. That said, when I’ve asked the question it shows that I’m already considering the above and how I might be a positive influence quickly. I’ve consistently gotten great answers to this question, and it also allows for an open conversation on how a candidates’ particular skill set could be leveraged immediately once hired.

Question #2

“Should you be moving fast and breaking things or moving slow and fixing things?”

Why ask this?

Facebook popularized the mantra of “Move fast and break things,” in an effort to fail quickly while continuing to grow from what was learned. While fostering a culture of continual learning is enormously valuable, not all problems can be solved by creating completely new products.

Continuing to cover up technical debt through a constant barrage of new features can be catastrophic. That said, many organizations are held hostage by successful products that continuously add features so much that innovation is completely stifled. It’s very helpful to understand both sides of this question and the value they can bring to a product’s design.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

How comfortable is the team with the idea of shipping a rough Minimum Viable Product (MVP), to gain insights quickly?

How risk-averse is the company or group or even the design team?

Is the business dealing with a very fragile codebase?

How frequently is tech debt refactored?

How is UX debt identified and managed?

How is this question received?

This is a very thought-provoking question for lean/agile organizations and the most common response I’ve received has been, “That’s a really great question,” and the ever-popular “It depends.” I’ve gotten fantastic responses by asking this as it affords an honest reflection on the current state of the business. The design team likely has an opinion on whether they are moving too fast or too slow and if they should behave a bit differently.

The answer doesn’t need to be a scary thing, but it should be honest and should afford some honest reflection. The best designers I’ve known appreciate hearty challenges they can dig into, and this question can provide additional clarity as to what you’re stepping into.

Question #3

“If you’re moving fast, why?

Why ask this?

Moving fast can be very exhilarating, but it may not result in productivity. To some stakeholders I’ve spoken with, the word “Agile” is synonymous with “I get my things faster.” In reality, being agile or ‘lean’ is about learning and delivering the right product or solution in the smallest way to customers. Moving fast can be very advantageous so long as it’s coupled with a willingness from design to show work that may not be perfect but is functional to the point of being usable. This is where moving fast is great; learning can be realized quickly and new product directions can be identified early. This can inform an interviewing designer on how data and research are being collected and distributed to other teams or the larger organization. Alternatively, if this isn’t happening, it could indicate a large opportunity for change or an unmitigated disaster so be on the lookout and follow-up accordingly.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

Are you trying to break things and learn from failure, or just moving fast because of #things?

Are you looking to gain mindshare in a new market?

How is the growth being managed?

How is the doubling or tripling of staff affecting team dynamics, agile health, or even the company culture?

What plan is in place for documenting and disseminating learning that has been gathered?

How important is this task for the organization and the work I do as a designer?

How is this question received?

This question and the next tend to be contingent on individual teams or parts of the company. I’ve also had it backfire a bit as it’s easy for someone to become defensive of their organizational behavior. One exuberant response I’ve heard is “We’re failing fast and failing often on our teams!” but when pressed with, “What have you learned from those failures? How has that learning been incorporated into the project and received by leadership?” responses were a bit uncomfortable. This is a massive red flag for me — honesty is tremendously important to me. Just be aware this can start to get into uncomfortable territory, but it can also speak volumes about a team or leader in how they manage their response.

Question #4

“If you’re moving slow, why?”

Why ask this?

Sites and applications are like rose bushes: if they aren’t pruned periodically they can get unruly and — eventually — downright ugly. Likewise, the continuous addition of new features to any code base without sufficient refactoring and paying down tech debt can create a very fragile product. The company may have started moving quickly to capture market share or breaking things in order to build quickly and try out changes to the tech stack.

From a design perspective, the biggest experience gains aren’t necessarily from a design system or improved onboarding. The company may need to modernize the tech stack to focus on improved performance or application up-time. The team may need to make changes to their delivery mechanism providing some form of Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CICD), a system where a designer can more easily implement A/B testing and better understand where the most impactful changes might be made.

Most designers would likely not give a second thought to the state of the tech stack because that’s an ‘engineering problem’, amirite? However, getting an up-front look at the state of the product from a technical perspective is immeasurably valuable, even to design.

Understanding where the company is in upgrading their systems, what frameworks are being used, and how willing they are to invest in the infrastructure of a legacy product provides a glimpse into the company or team priorities.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

Which parts of the site/application/product are least-effective?

Should they be retired or reinvested in?

How might these upgrades impact day-to-day work?

Are new features being prioritized into the new product development so we can phase out aging systems?

How will these changes impact customers?

Can they still get their jobs done in the new system or are they going to be retired?

How is that being communicated to users?

Has there been any communication around sunsetting these retiring systems to lessen the burden?

Has any analysis been done to understand how much revenue is provided by those users whose features are about to come to an end?

How is this question received?

This line of questioning has typically been handled offline as managers I’ve spoken to didn’t have the answers handy. They were typically fielded by an IT or Dev manager, who was more than happy to see that level of interest from a designer. As a designer, I don’t need to understand the details of my team’s API end-points, but I should understand something about the health of my digital product.

The interview process is about mutual discovery—learn as much about your potential team and organization as they are learning about you. (Large preview)

Question #5

“What are the three pieces of your product that are most valuable but also in the most need of an update?”

Why ask this?

This question is all about priority and, similar to the prior question, this could be digging more into the tech stack of the product. My reason for asking actually has more to do with the “core loop” of the product. The core-loop is the dopamine hit that attracts a user and keeps them coming back to enjoy the product repeatedly.

It’s akin to the food pellet that makes a rat respond to stimuli. It can also be a prime pain-point that’s a massive trigger for catastrophic system failure, and thus ultimate fear within the team. “Don’t do anything to this or our entire system could shut down.” When considering some changes to that legacy system perhaps we simply leave it alone, but we might enhance it in another way leveraging something more modern as an overlay or in a new tab or window?

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

What is standing in the way of doing this work?

What team members could we talk to about these features?

Have they done any research to understand what’s causing the behavior to be erratic or difficult to maintain?

What users can we speak with about the features to understand how they’re using it?

Perhaps there’s a slight tweak that could be made enabling the same outcome, but putting less stress on the system?

Are there small tweaks that could be made to relieve pressure on the back-end and reduce strain on the database?

How is this question received?

Similar to the prior question, this can quickly get technical but it doesn’t have to. I’ve posted the question to a hiring manager who also forwarded it to a member of the product and dev teams who all gave slightly different answers. As suspected, they all provided some overlap which clearly showed what the most important problem was to work on from the business’ perspective. Don’t hesitate to ask they forward the inquiry on to someone who might be better suited or could provide a more nuanced response. Gathering broad viewpoints is a hallmark of what we designers do well.

Question #6

“Do you have a customer I might contact to get their thoughts about your product or service?”

Why ask this?

This may be the boldest question on this list, but it provides so much amazing value as an incoming designer. If we are operating as practitioners of a human-centered approach, we should be comfortable talking to users and our employer should be comfortable ensuring we have access to them. Granted, you may not yet be a member of the team, and they’re not yet your customer. But putting a willing foot forward in this area speaks confidently that you would love to get first-hand access to customer feedback.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

How familiar is your team talking to their users?

How often does this activity take place?

Assuming this customer is a fan of the company, do we have access to users who aren’t so happy with the product?

Do we ever seek feedback from someone who has canceled the service?

How might the team use any insights you bring back to them?

How is this question received?

This question is bold and can be a bit tricky. Sometimes the team doesn’t have a good customer in mind, or even if they do, they don’t have ready access to them as customers are handled by a separate gatekeeper. At the same time, I would expect most companies to have a short-list of customers who think they’ve hung the moon. The marketing department tends to plaster their quotes all over the home page so feel free to look for that prior to the interview and ask for those contacts directly.

When asking this question, I’ve also provided the questions I was intending to ask as well as the answers I got back. With free user research on the table and an opportunity for the marketing team to gain additional positive feedback asking this worked out in my favor, but that won’t always be the case. Be gracious and understand if someone’s not comfortable providing this access, but it’s a strong play in expectation setting for a human-centered design practice.

Question #7

“What is your dedicated budget for UX and design?”

Why ask this?

If the value of user experience is wrapped up solely in market research, then the company doesn’t understand a human-centered approach through their users. Market research can certainly be valuable by informing the company if a business idea might be financially viable. However, user research can guide the organization in delivering something truly valuable. This question can help a prospective designer understand that the company sees design as an investment and competitive advantage.

What follow-ups might provide more insight?

What percentage of your overall expenditures does this represent and why?

What is the highest-titled member of the design team?

What is the education budget in a given year for training or events?

Has this grown, shrunk, or stayed flat compared to the prior year?

What are the growth areas for the design team overall, i.e. where is the design investment focused?

Research?

Visual design?

Copywriting?

Architecture?

How is this question received?

This is honestly more of a leadership question, but it can be tailored to even an entry-level position. Any organization without a clear operating budget for design isn’t taking the practice seriously nor its practitioners. Product, engineering, and design are the components of a balanced team. Funding one at the behest of another is a dumpster fire and clearly communicates that the balance is out of alignment.

The easiest answer I’ve been given is the salary and position I’m applying for, however, that shows a lack of foresight in terms of both growth for the team by way of headcount, as well as properly empowering designers to do their best work.

Discussions during an interview. You have the floor so use it to your advantage. (Large preview)

Just The Beginning

These are just a few of the types of things we could be talking about during experience or product design interviews. We certainly should care about excellent visual design and elegant UI. We should absolutely care about qualitative and quantitative analytic data and the insights they provide. We should definitely care about motion design, user flows, journey maps, design systems, microcopy, and culture fit. These are all part of the playbook of any strong, digital-design candidate. But the answers to the above topics can be incredibly impactful for the first 90 days and beyond when assuming a new design role.

You may not be able to ask these questions in a face-to-face discussion, but they make a great follow-up email after an interview. Or perhaps they’re questions you keep in the back of your mind as they’ll inevitably come up in your first few months on the job. They could prove very useful to guide a longer-term, strategic vision that empowers you to improve the business by crafting glorious engagement with both your teams and your customers.

Does Asking These Things Actually Help Get The Job?

I’ve been asked if these questions were helpful in landing a better job and truthfully, I don’t know. I did find a very rewarding new position as a Principal Product Designer, and I used these questions throughout the interview process. After I was hired, I spoke to a couple of folks who were part of that process, and they mentioned the questions, so they were at least memorable.

The entire line of questioning has also resulted in the opportunity to co-author a book around using design to address organizational change and reconsidering how the field of experience design is currently defined. I would posit both of these opportunities were impacted in some way by these thought-provoking questions, even if the projects have yet to be fully realized (we are just starting work on the book, but it’s a very exciting concept).

I also used the questions in interviews with several different companies and ultimately, I was able to entertain multiple offers. Through each interview using these questions allowed me deeper insights about the organization than I would have had otherwise. Did the questions directly help me get the position? Of that I’m unsure, but they were absolutely beneficial for both my own awareness and for the team I eventually joined.

Final Thoughts

Approaching the job interview process more like a researcher gave me a very different perspective on the process. Interviewing can be a stressful event, but it can also be a mutual glimpse into a shared future. Any prospective employer is inviting a designer to embark on a life journey with them — or at least a year or two — and the interview is where the two parties really start to get to know one another. The answers to these questions can help paint a more transparent picture of the shared road ahead for both the designer and the teams they might partner with.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments, and whether you have other tough questions you’ve asked during interviews. I would love to know how they’ve been received and continue adding to my own list!

Further Reading

“How You Can Find A Design Job You Will Truly Love,” Susie Pollasky

“Facebook Changes Its ‘Move Fast and Break Things’ Motto,” Samantha Murphy, Mashable

“Sprints & Milestones” podcast by Brett Harned and Greg Storey

“Playbook” offers career advice for designers via crowdsourced Q&A

“Dear Design Student” is a collab from some amazing industry veterans providing wisdom to up-and-coming design talent. #invaluable

(mb, ra, yk, il)

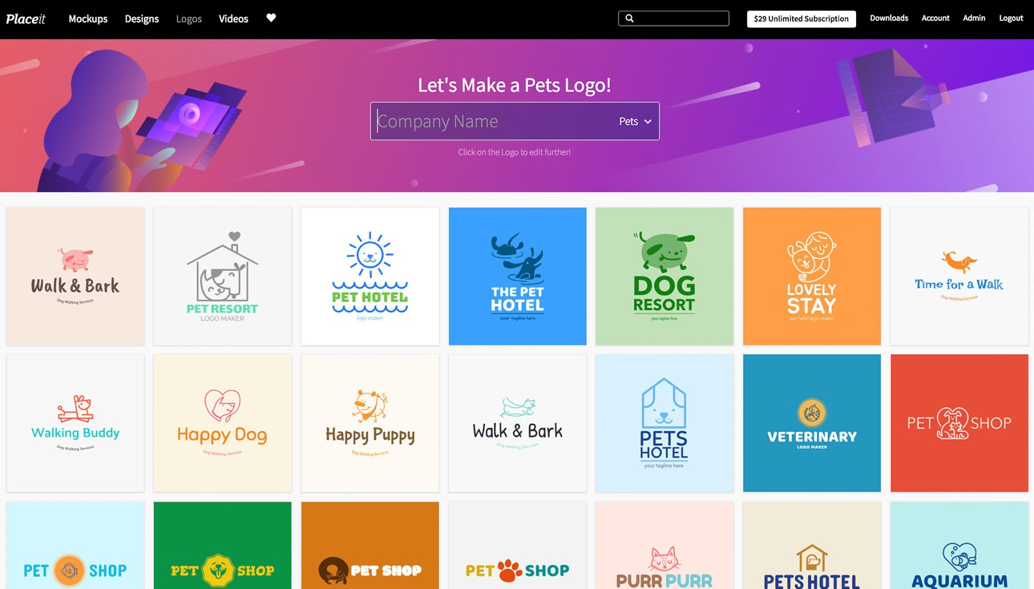

Placeit offers thousands of smart templates which you can customize by simply clicking a few options, while still keeping a professional layout. You won’t have to worry about resolution, dimensions or proportions. We promise your designs will always look sharp since there’s no way you can mess it up.

Placeit offers thousands of smart templates which you can customize by simply clicking a few options, while still keeping a professional layout. You won’t have to worry about resolution, dimensions or proportions. We promise your designs will always look sharp since there’s no way you can mess it up.

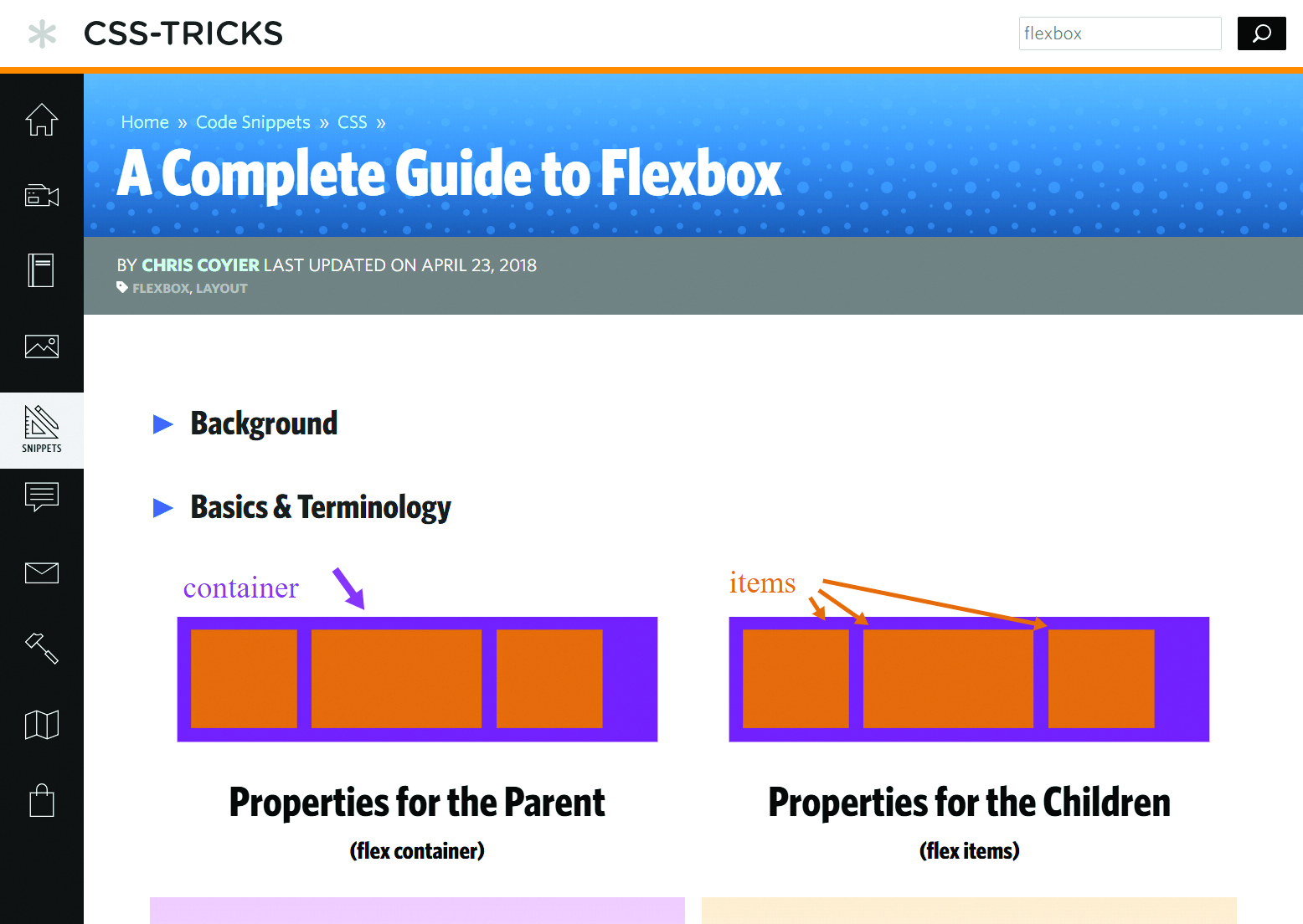

CSS Grid and CSS Flexbox are complimentary web layout technologies that have been hotly anticipated for years. However, despite some superficial similarities they are actually used for very different tasks; they each solve a very different set of problems.

CSS Grid and CSS Flexbox are complimentary web layout technologies that have been hotly anticipated for years. However, despite some superficial similarities they are actually used for very different tasks; they each solve a very different set of problems.