Original Source: https://www.webdesignerdepot.com/2020/06/5-ways-to-build-codeless-websites-using-wordpress-gutenberg/

Web designers could be forgiven if their eyes glazed over at the mere mention of building a custom website. Creating an advanced website used to require programming knowledge and hours of coding.

Web designers could be forgiven if their eyes glazed over at the mere mention of building a custom website. Creating an advanced website used to require programming knowledge and hours of coding.

But thanks to Gutenberg, even those who don’t know their HTML from their CSS will be able to create professional websites that stand out from the competition.

The initial feedback to the release of Gutenberg certainly was damning: “…Useless…A joke…Terrible…”

You can argue about how WordPress handled the launch of its new content block editor (and you might be right in thinking it wasn’t great) but the dirty secret is that, after a number of updates, Gutenberg has evolved into an excellent tool for building websites.

Below I will show you 5 ways a web designer with limited coding experience can take advantage of Gutenberg to build the types of custom websites that businesses are looking for.

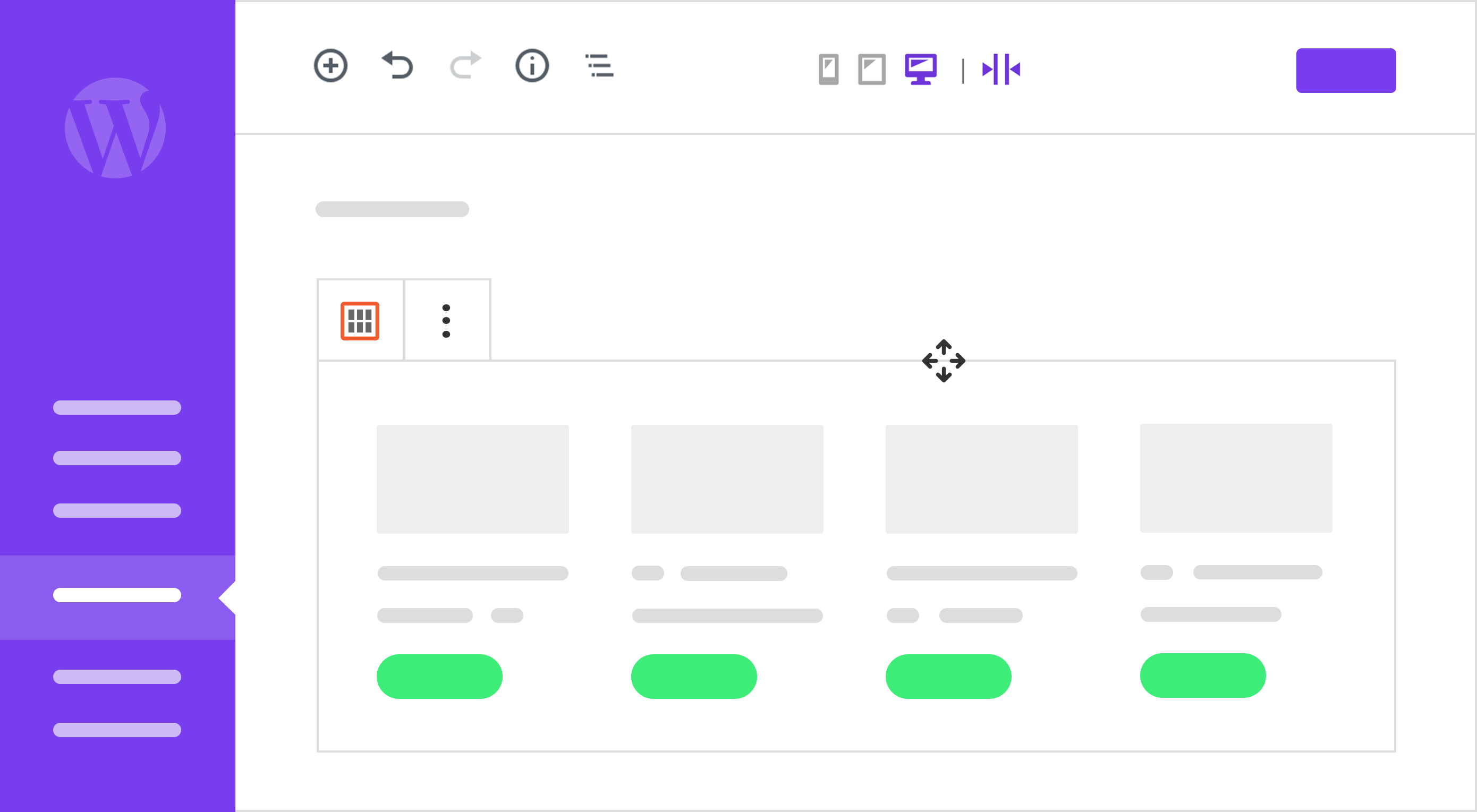

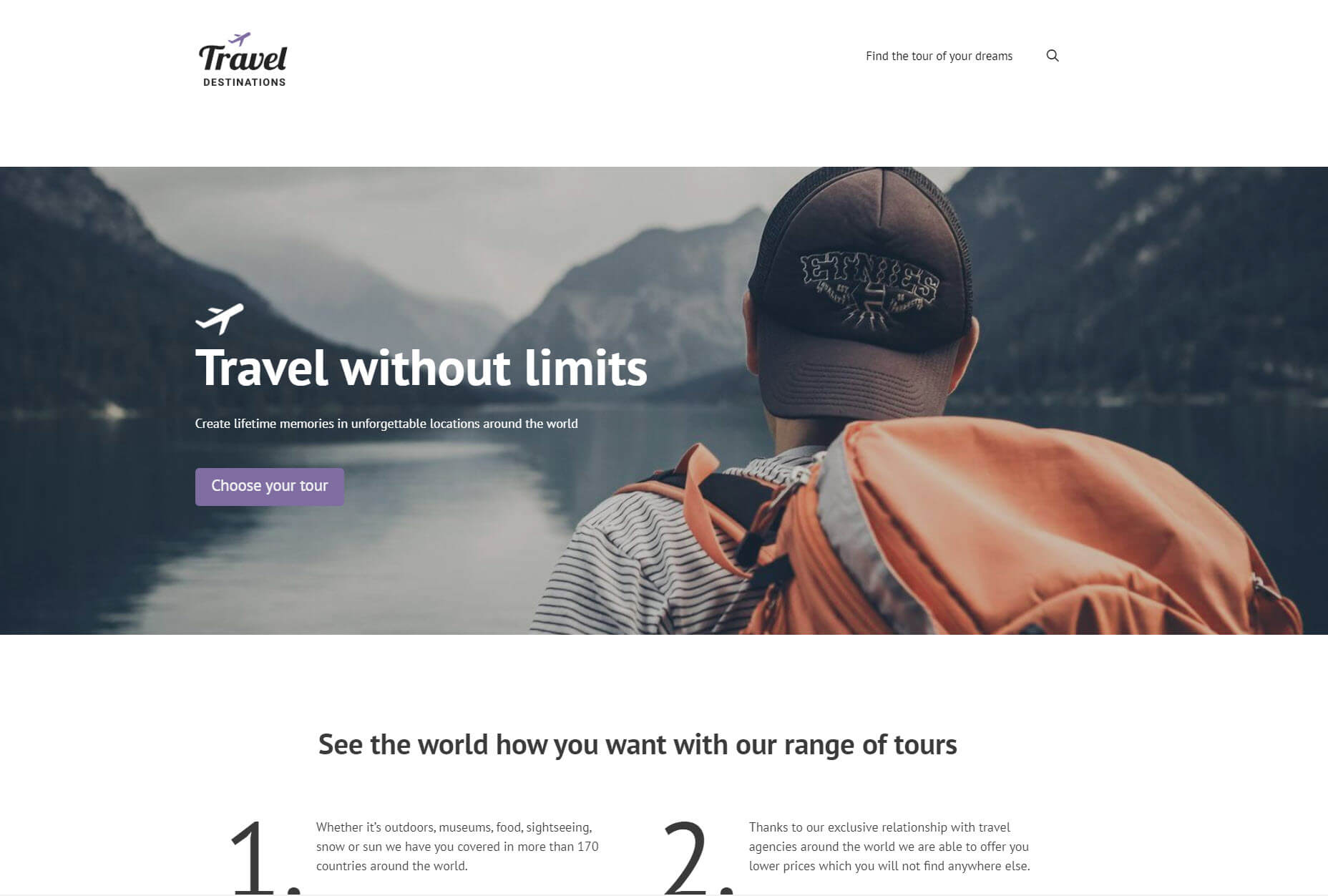

I created a travel website with a number of custom features using these three tools:

Gutenberg

Toolset – Its new Toolset Blocks allows you to add custom features to your websites including custom post types, a search and dynamic content.

GeneratePress – A lightweight and fast theme that is easy for beginners to use.

Now I’ll let you in on a secret. I’m not a developer. In fact, I have limited coding experience. Yet I was able to use Gutenberg to build a professional website with a number of features that custom websites would require. Below I’ll go through five of them.

1. You Can Create Dynamic Content

An advantage it has over page builders is that Gutenberg comes with a number of block extensions to enhance your websites. One of those is Toolset which offers dynamic content capabilities.

Dynamic content means you can create an element (such as an image) that will draw the correct content from the database. So when you create a list of posts you only need to add each block for each element once, but that block will display different content for each post.

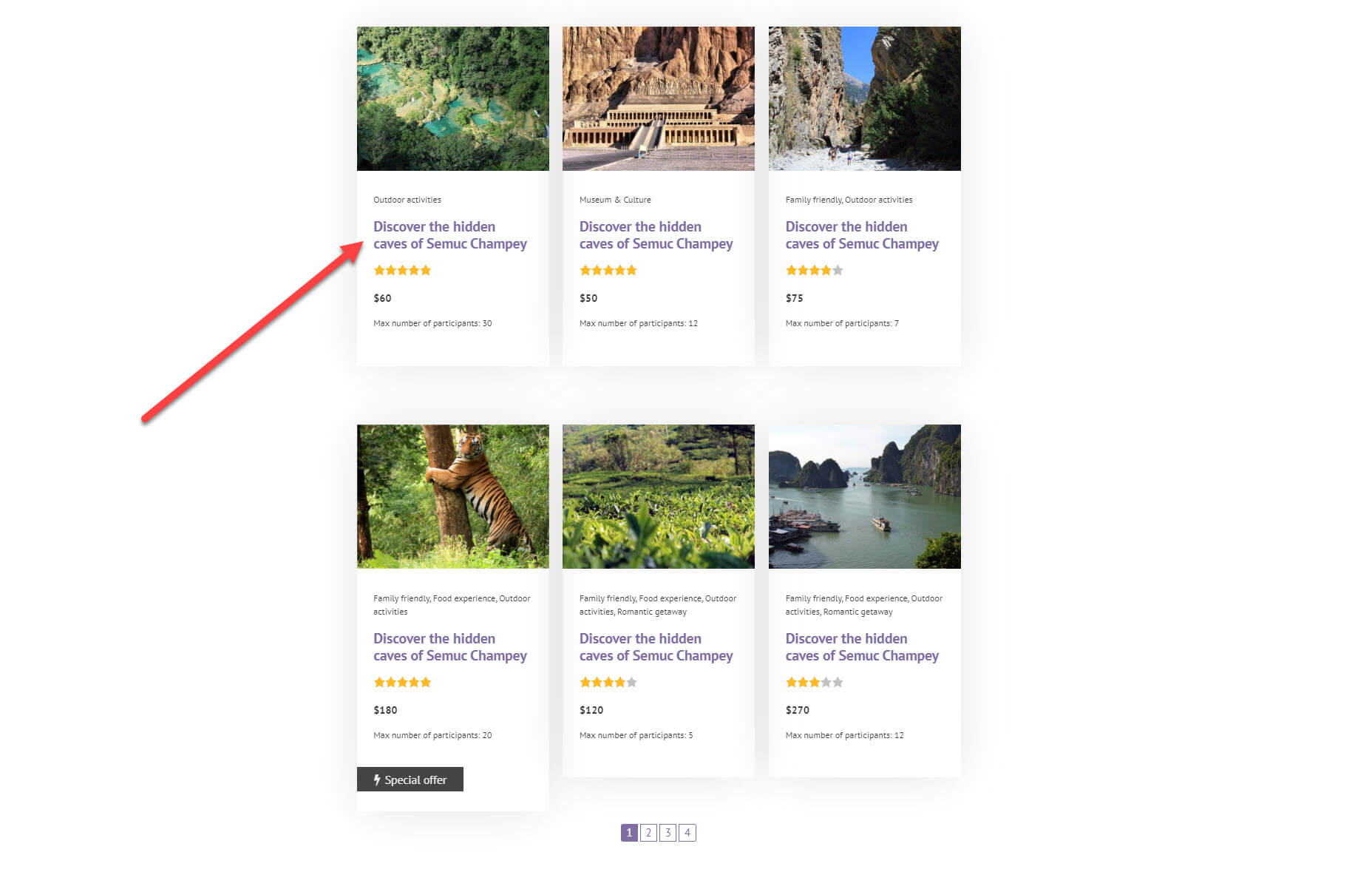

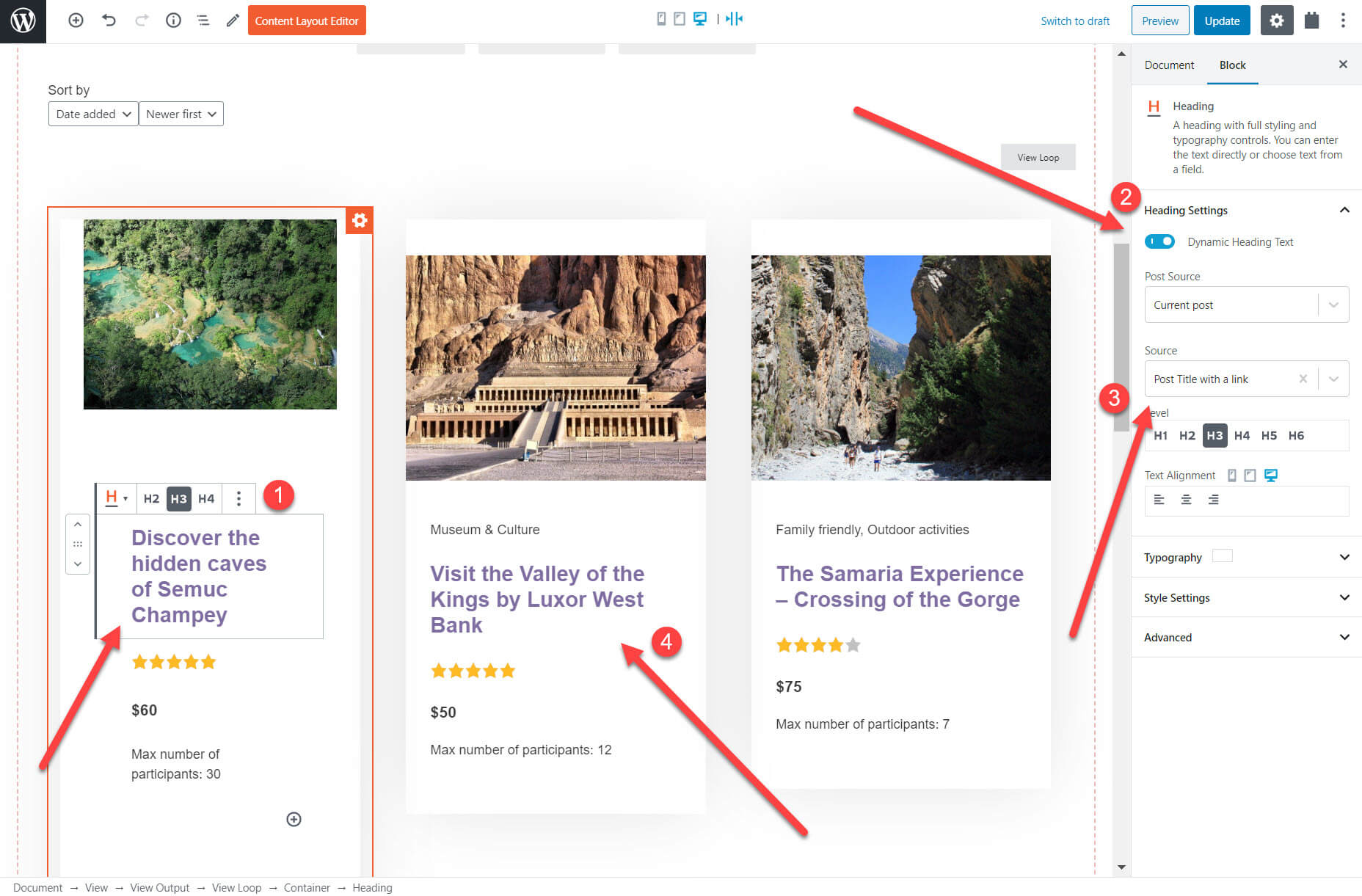

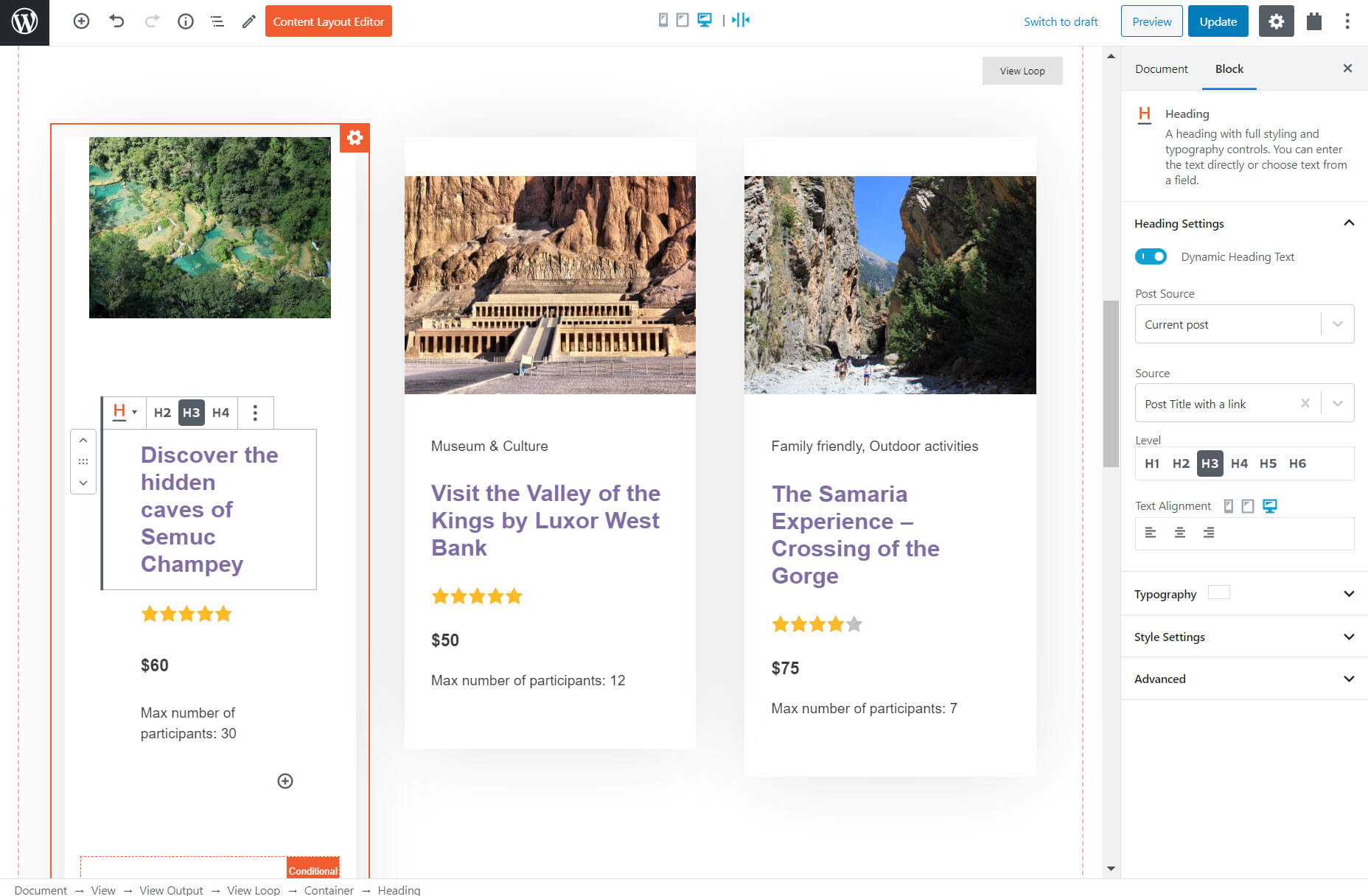

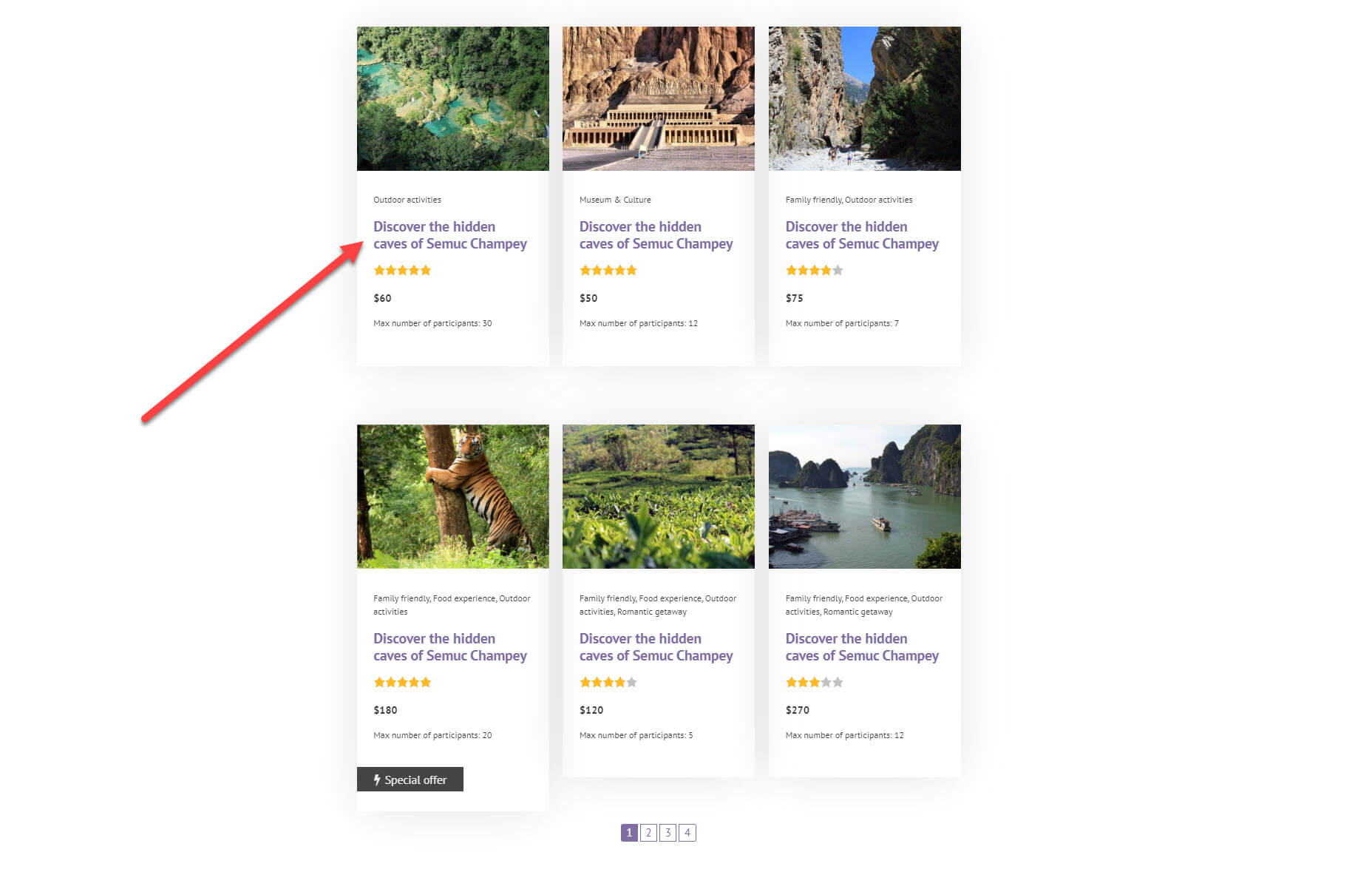

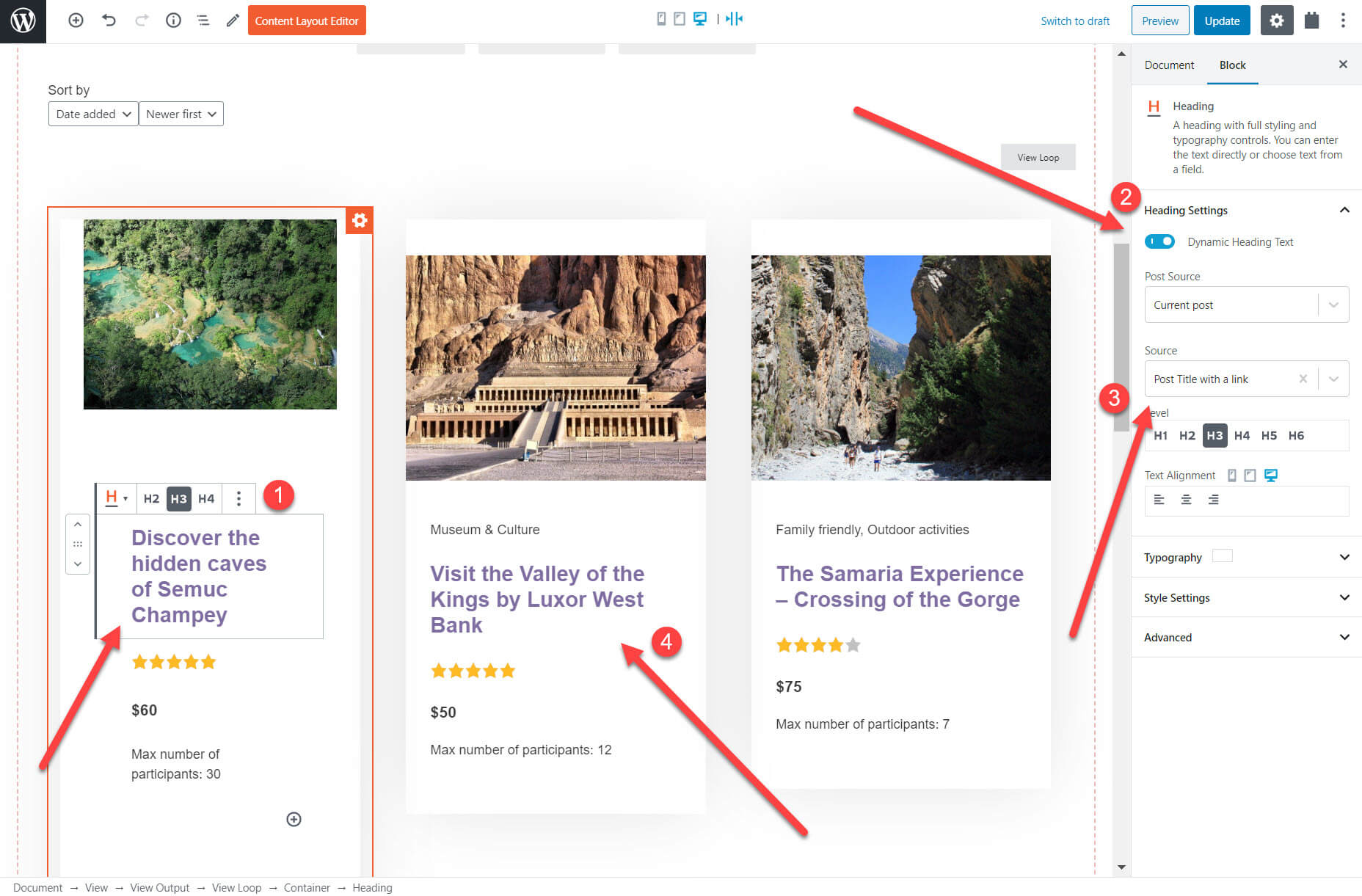

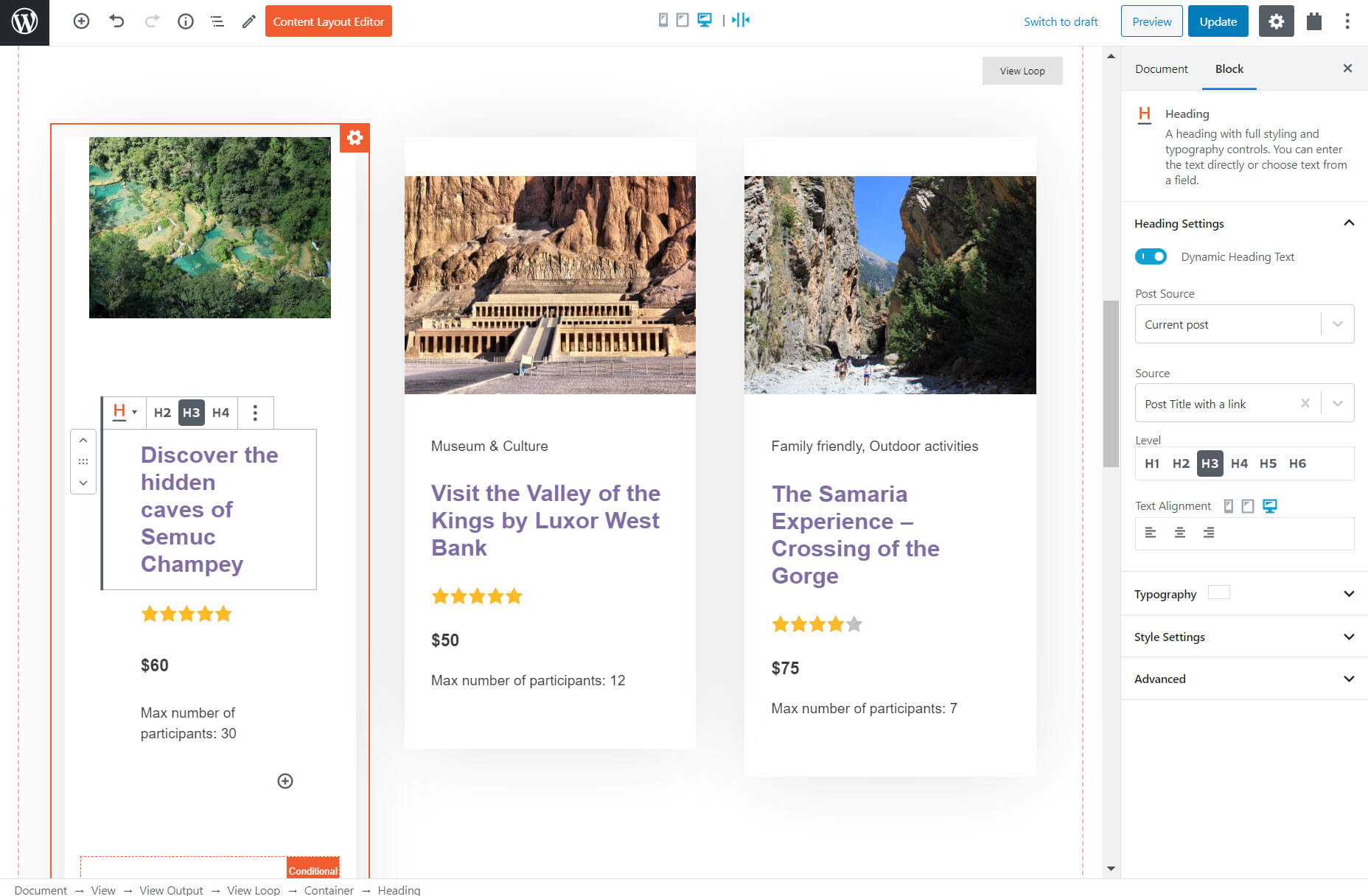

For example, I’ve created a list of tours posts – later I’ll go into how you can do this with Gutenberg. Do you notice something strange about the headings below?

The heading is exactly the same for each of my tours. That’s because the headings are static, the opposite of dynamic. It means when I add my blocks, whatever text I enter in the heading will be displayed for each of the posts. However, when it is dynamic, you will see the correct heading on every tour.

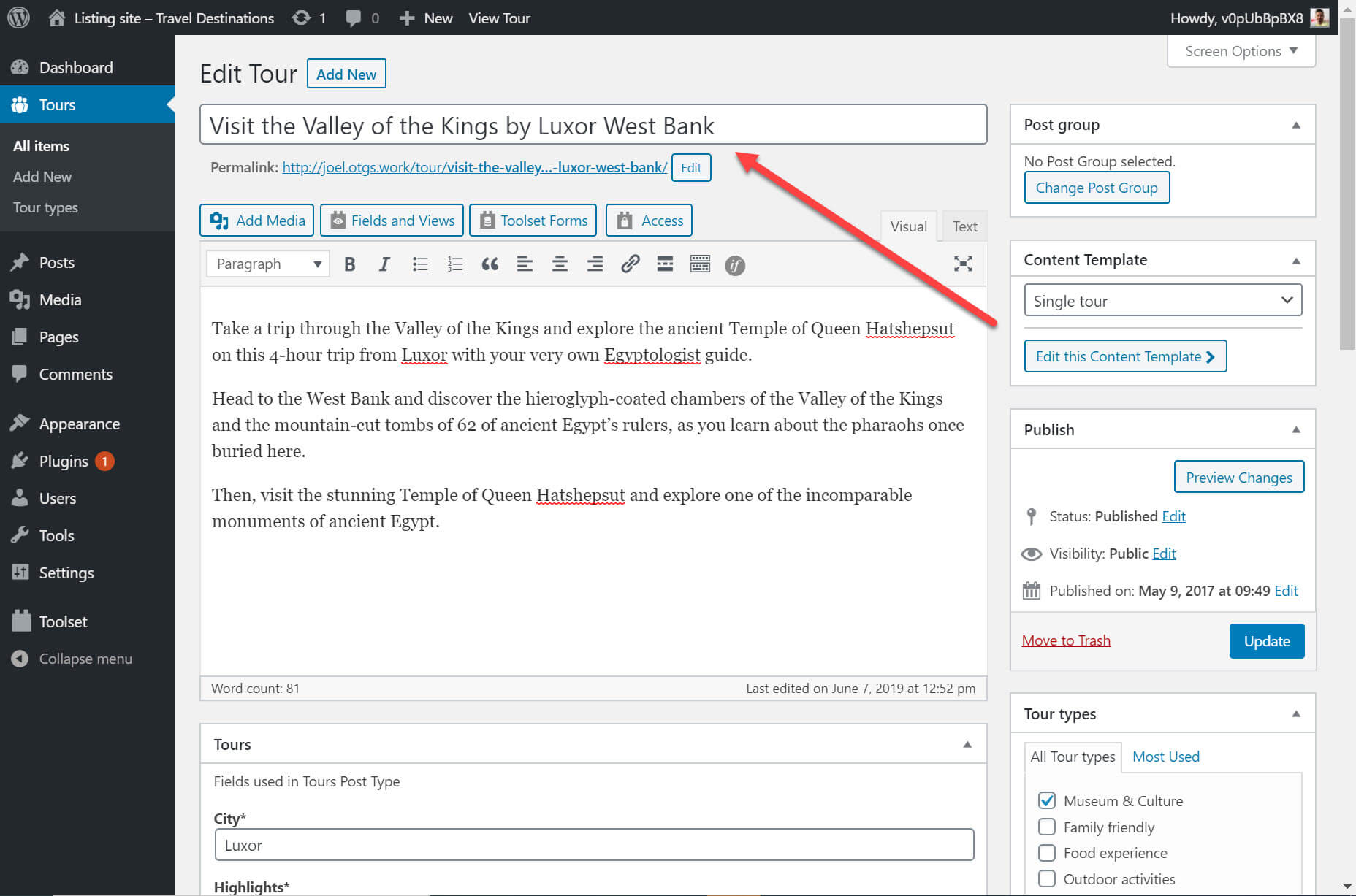

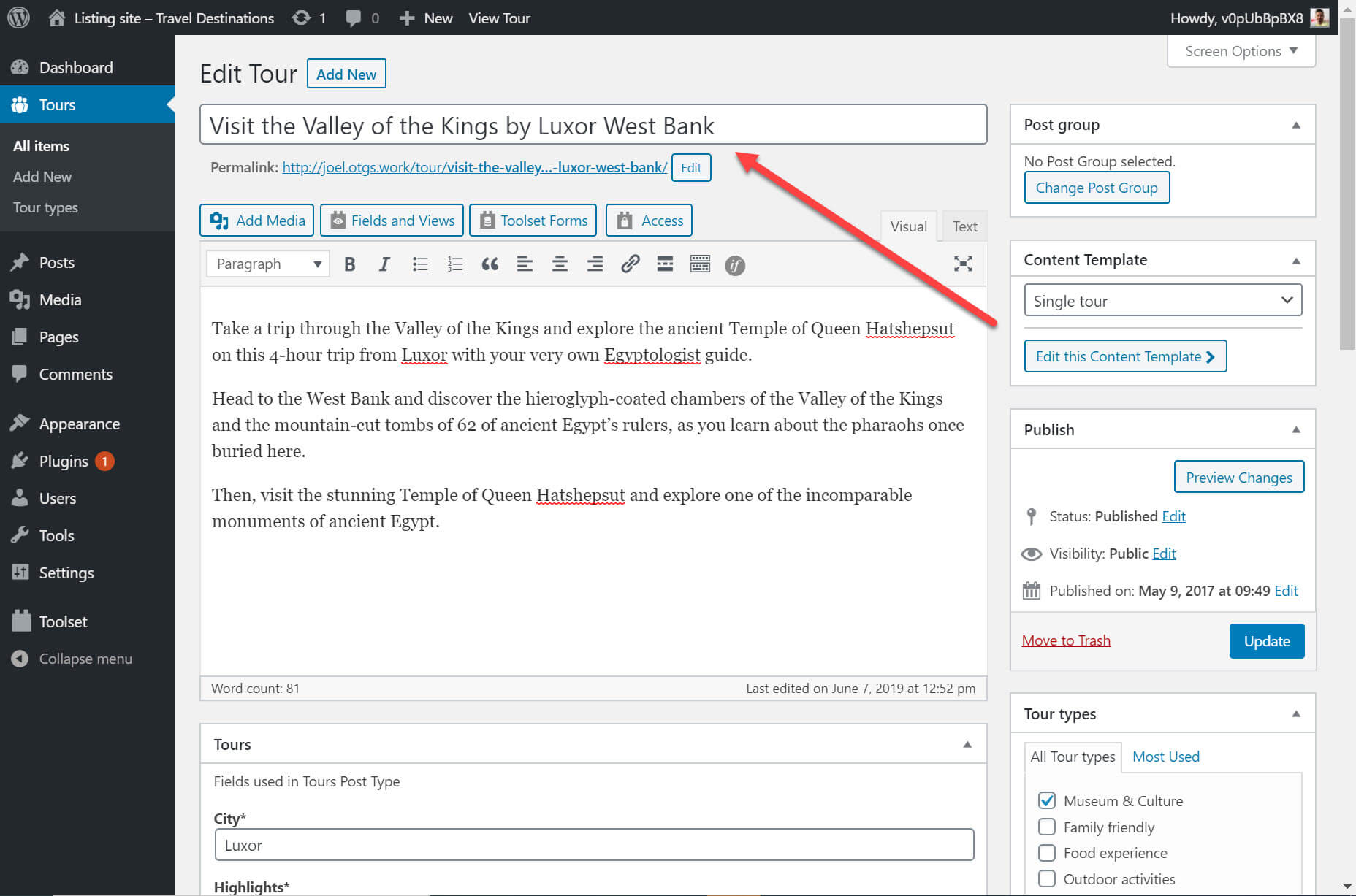

To illustrate, here is my tour post about visiting the West Bank on the back-end. You can see the post title at the top.

I want to display this tour post with the correct heading in my list of content. All I need to do thanks to Gutenberg and Toolset is the following:

Select Toolset’s heading block — unlike the normal Gutenberg blocks, Toolset’s allows you to make your content dynamic;

Select the dynamic option;

Choose the source for your heading;

Confirm that the heading is correct.

You can create dynamic content for a number of other blocks available on Gutenberg including images, custom fields and the link for buttons.

2. Display Custom Lists of Content

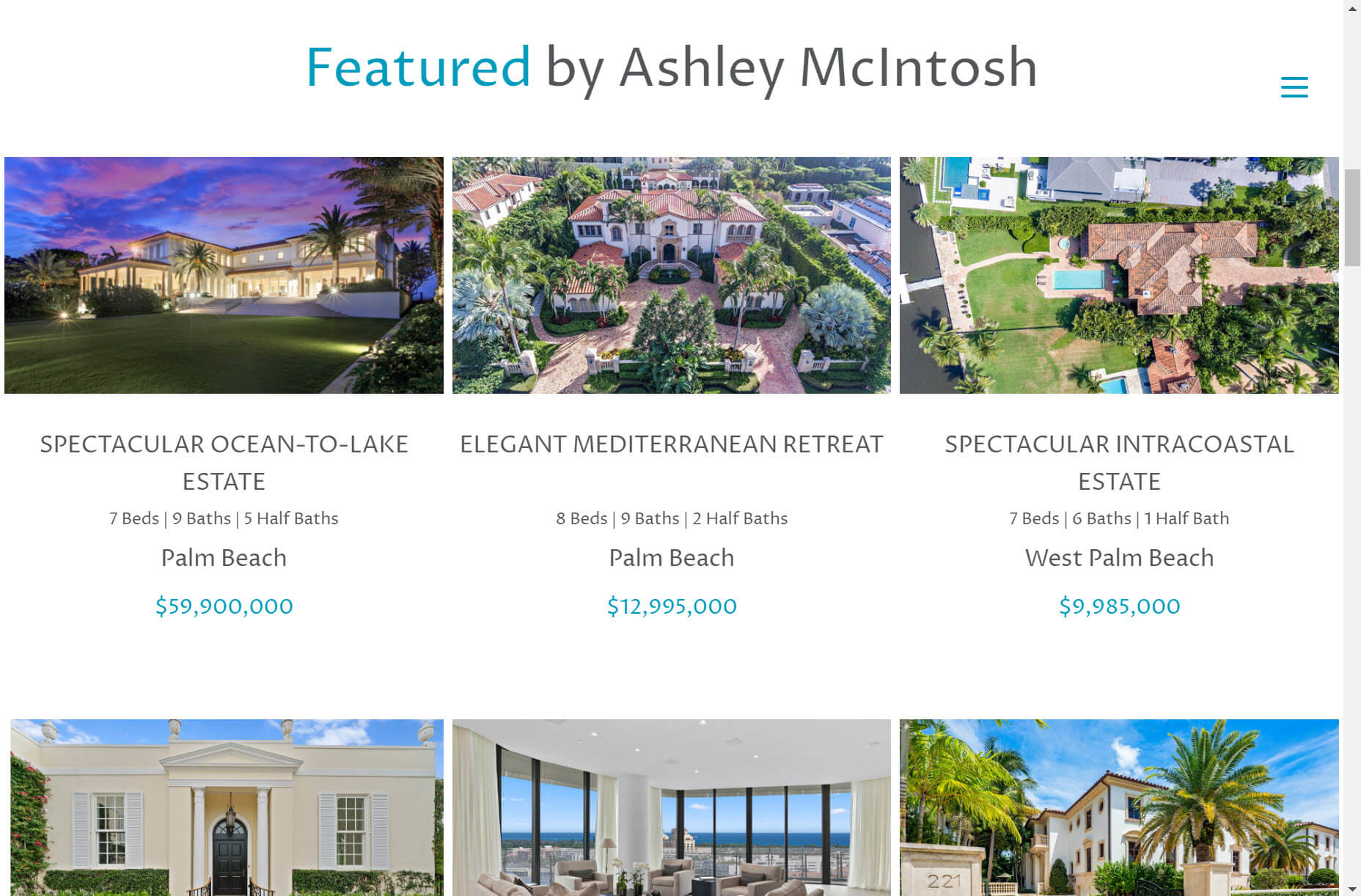

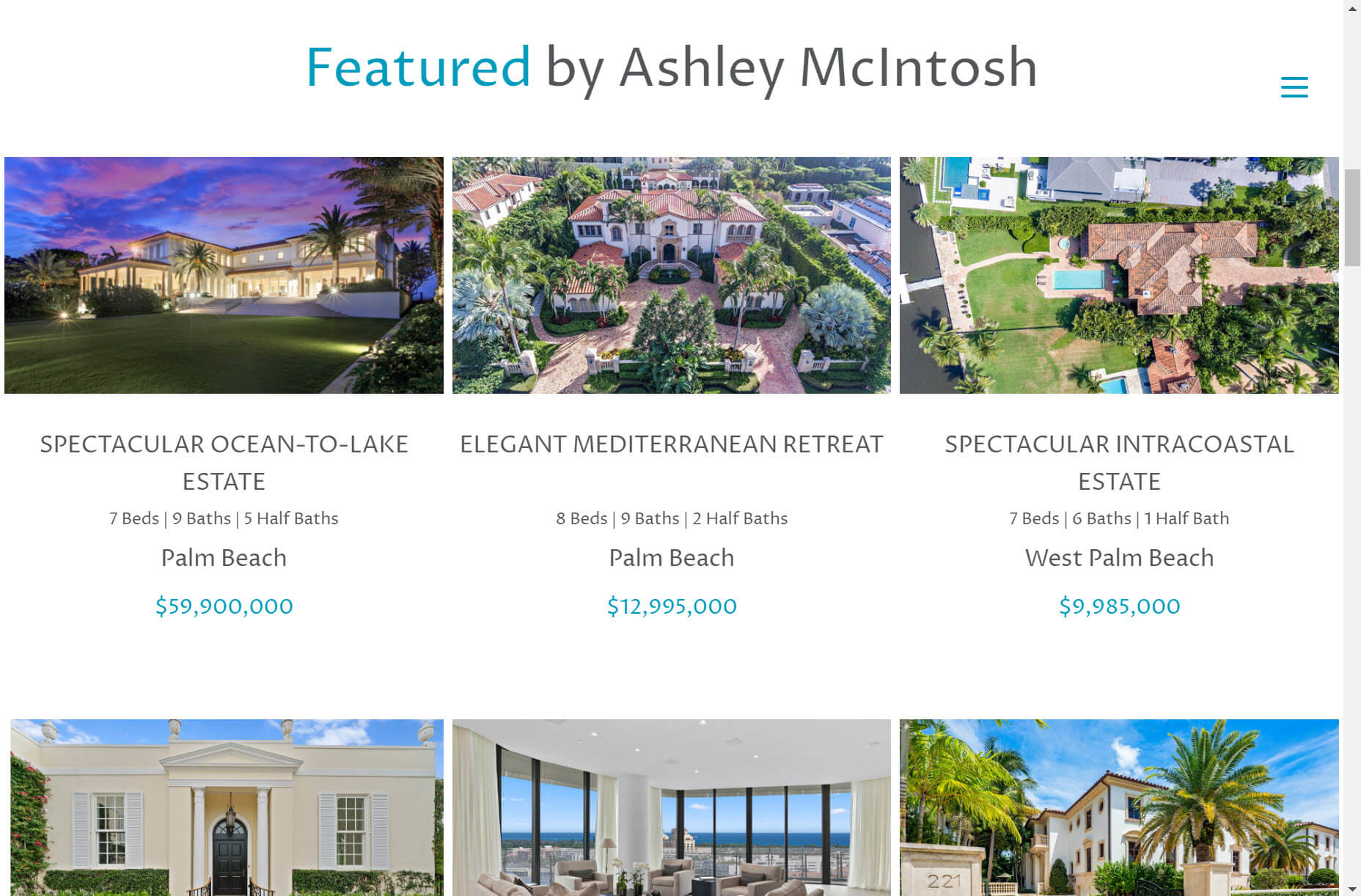

On a custom website, there will be times when you will want to list your content from a particular post type on different parts of your website. For example, a list of properties for sale on your real estate homepage.

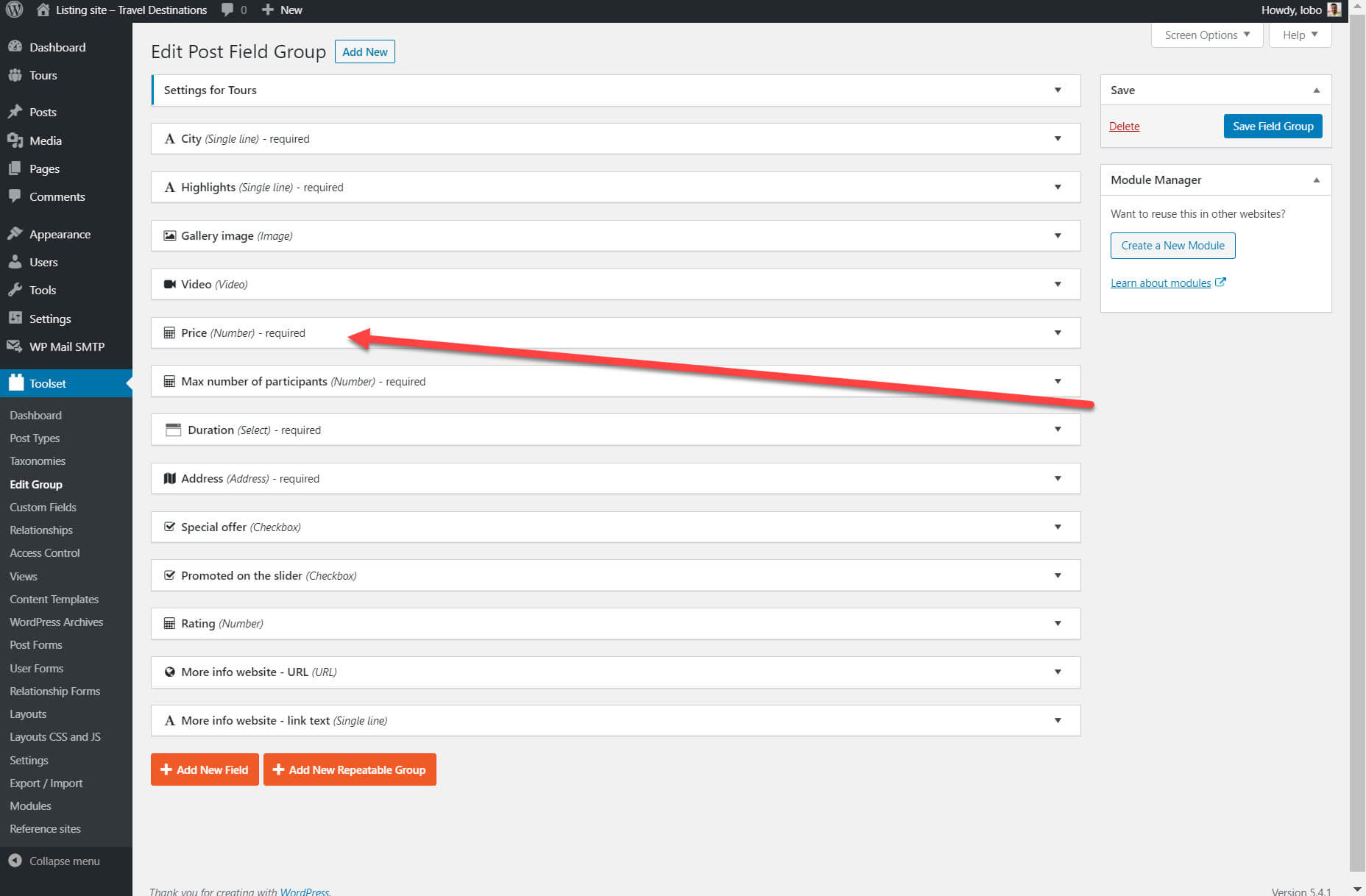

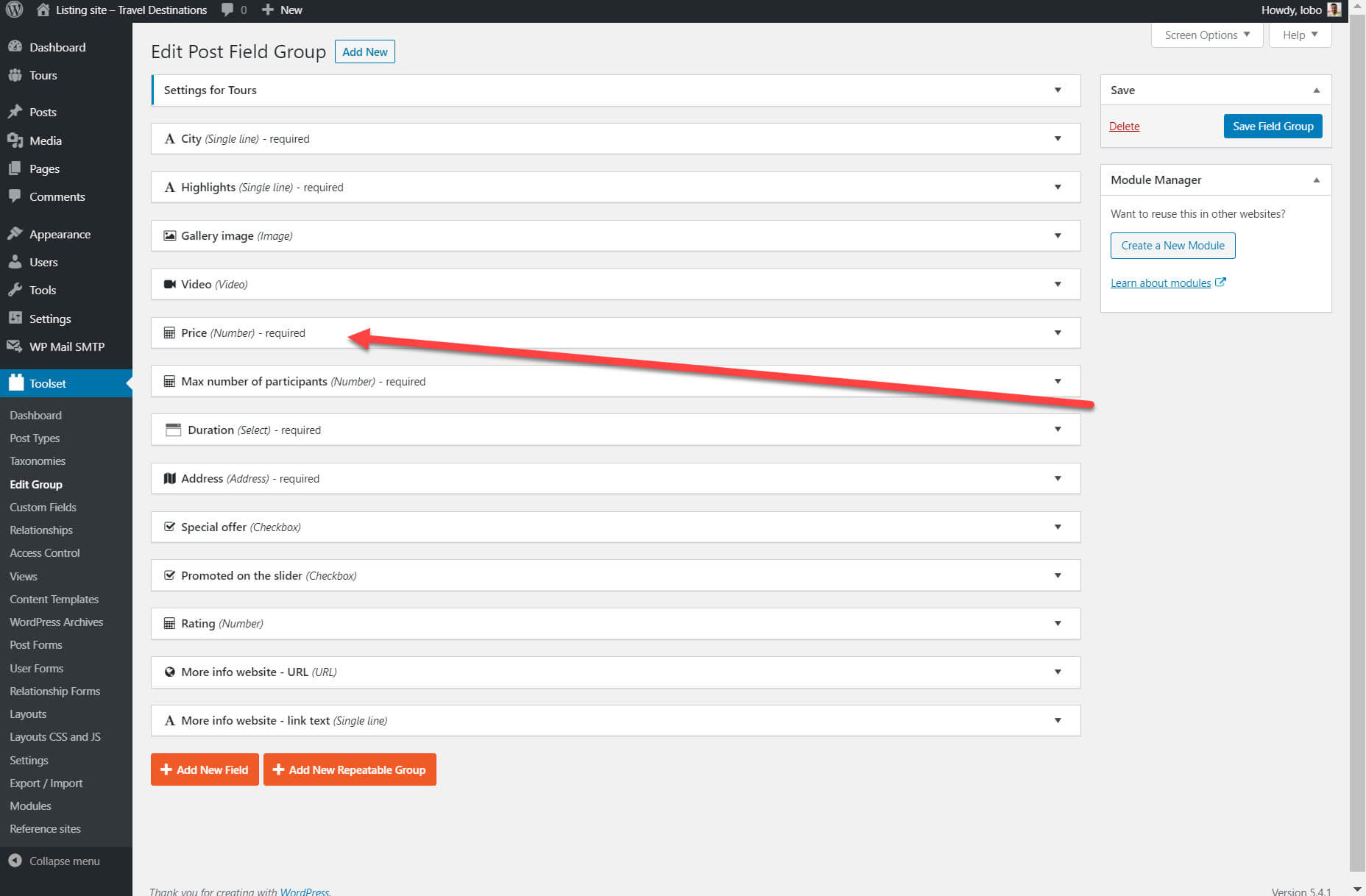

Each of these properties uses the same layout, displaying the same information such as the price, number of bedrooms and number of bathrooms in the same way. This information is added using custom fields which are pieces of information you can add to WordPress content. Page builders on their own can’t build custom fields. However, you can create them using Gutenberg and its blocks plugins.

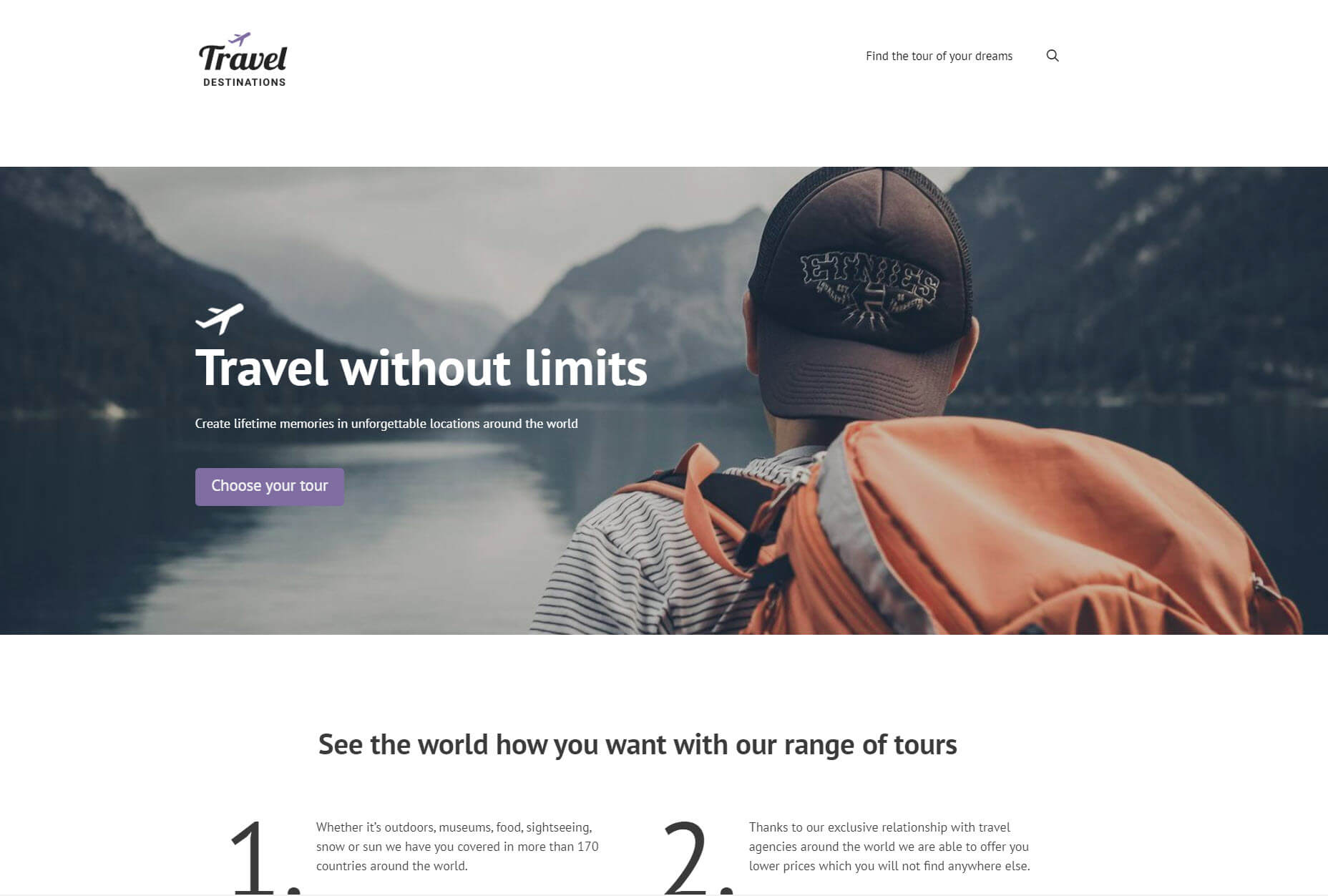

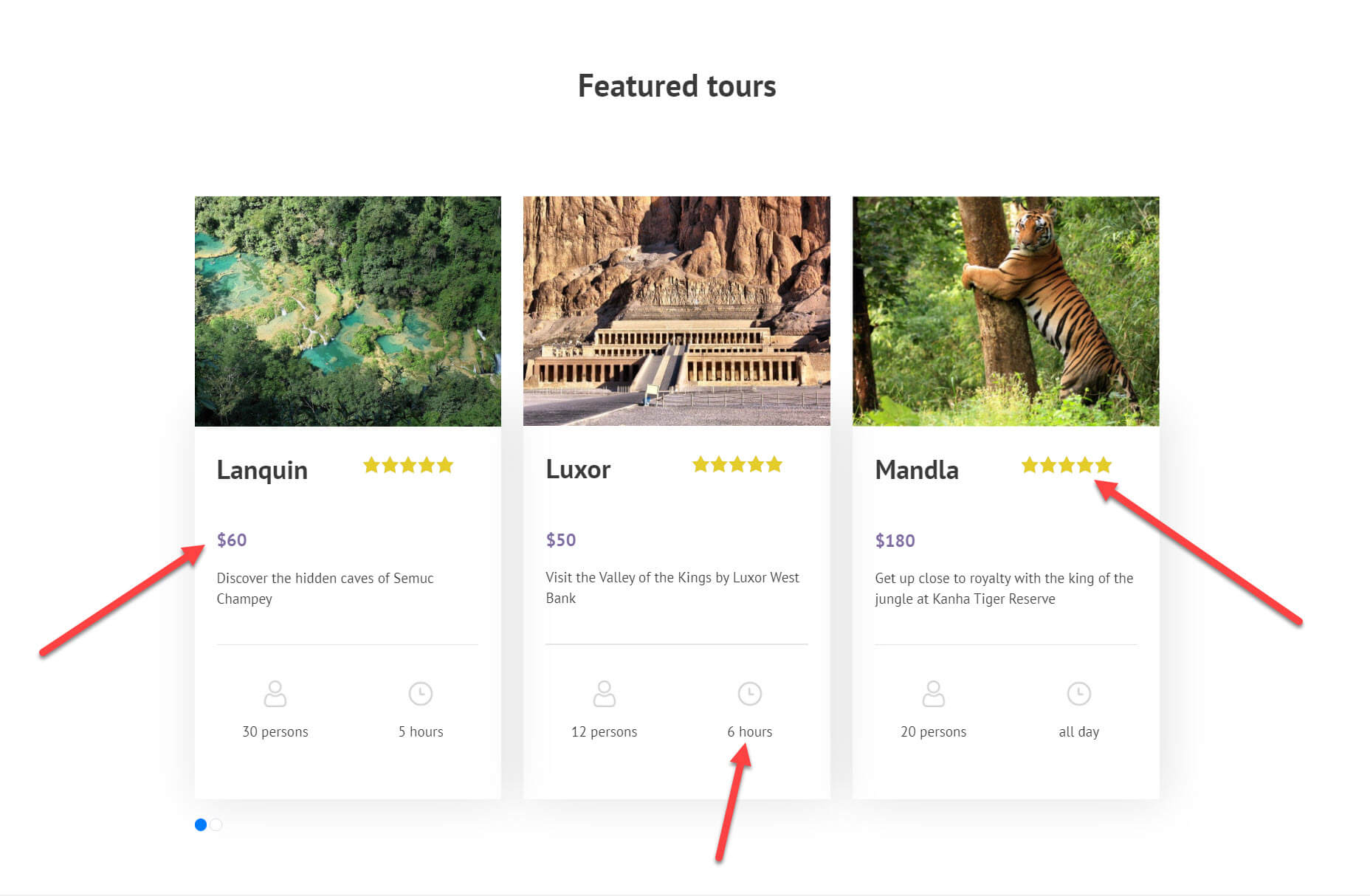

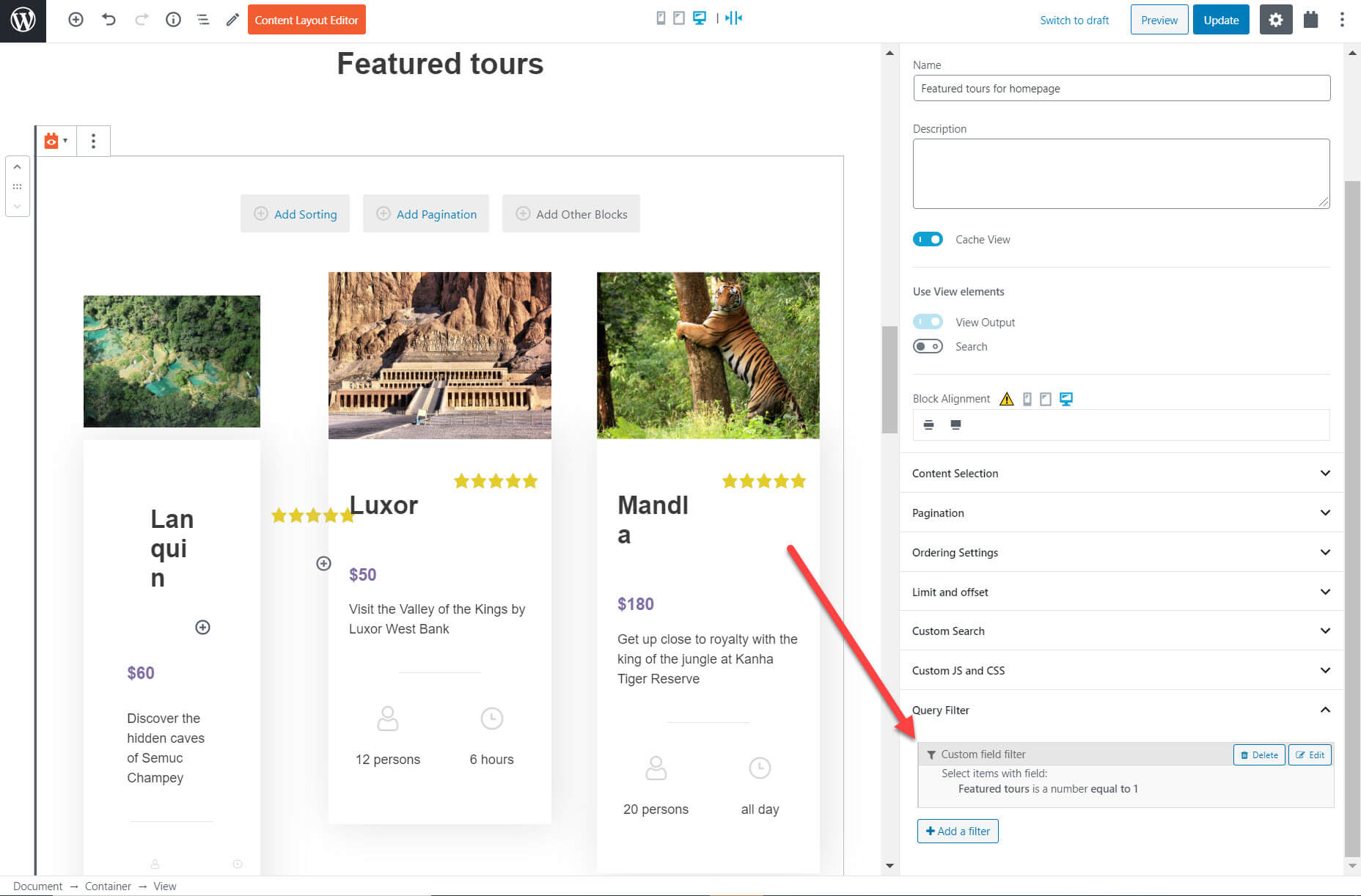

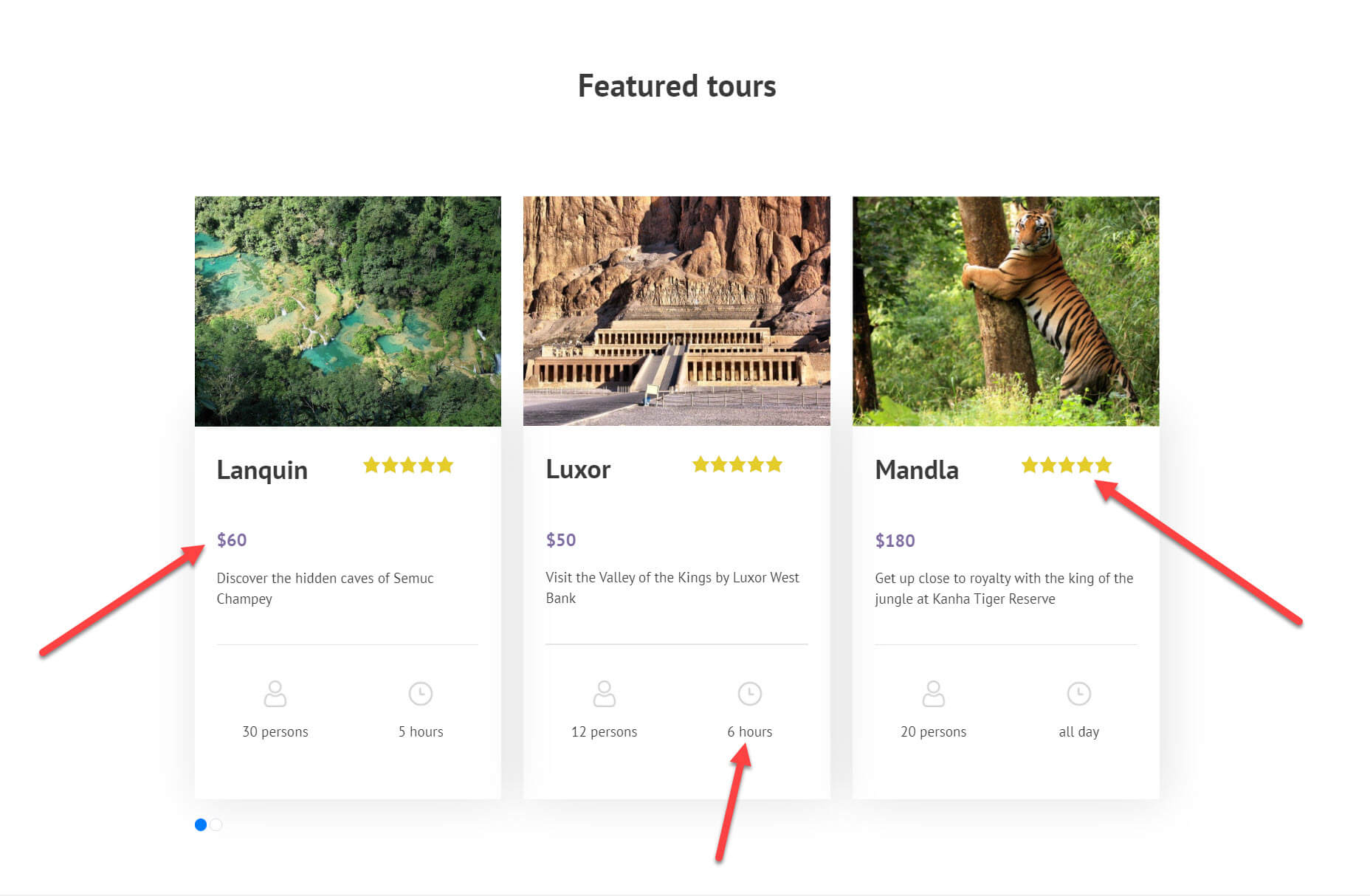

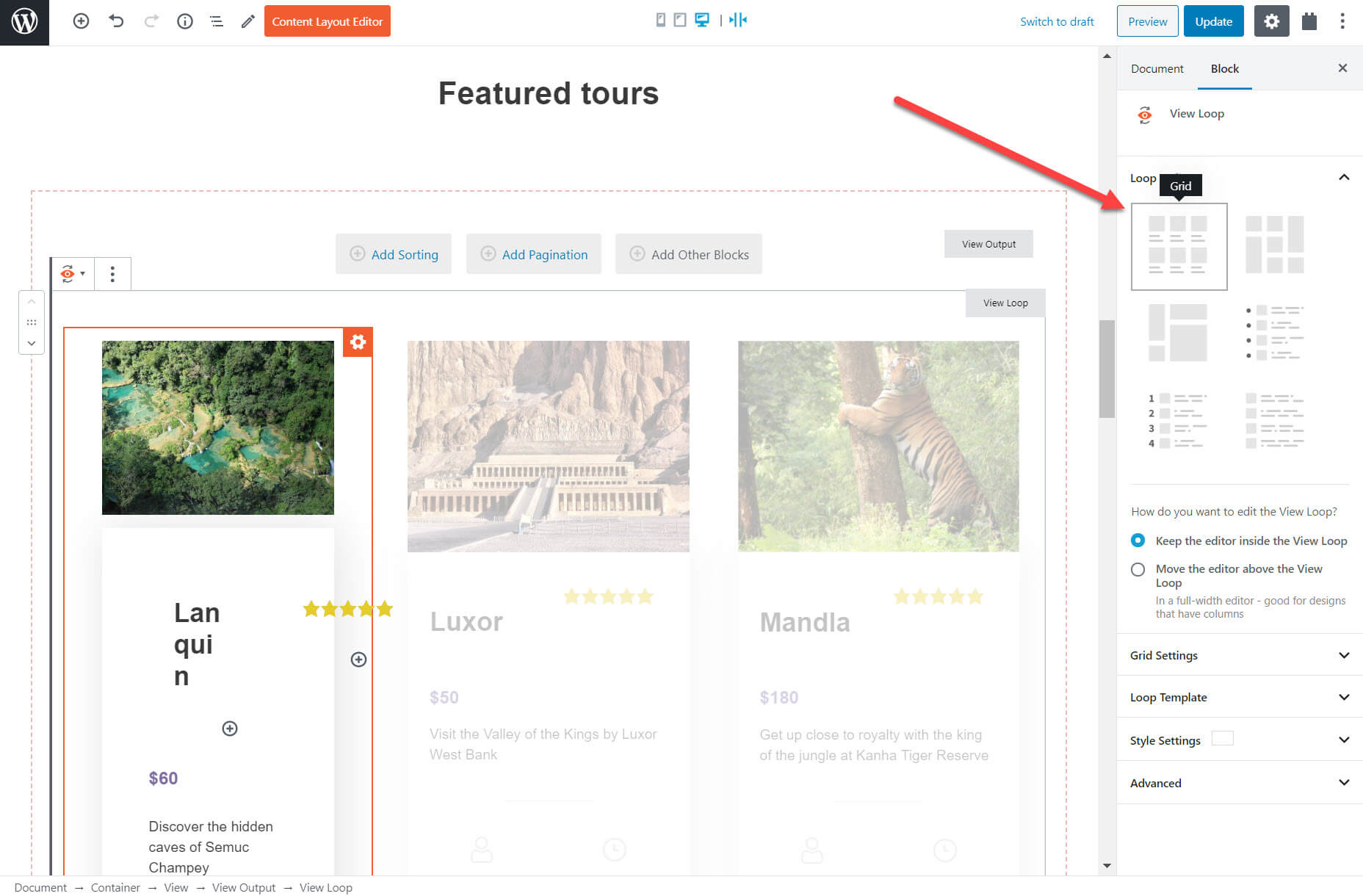

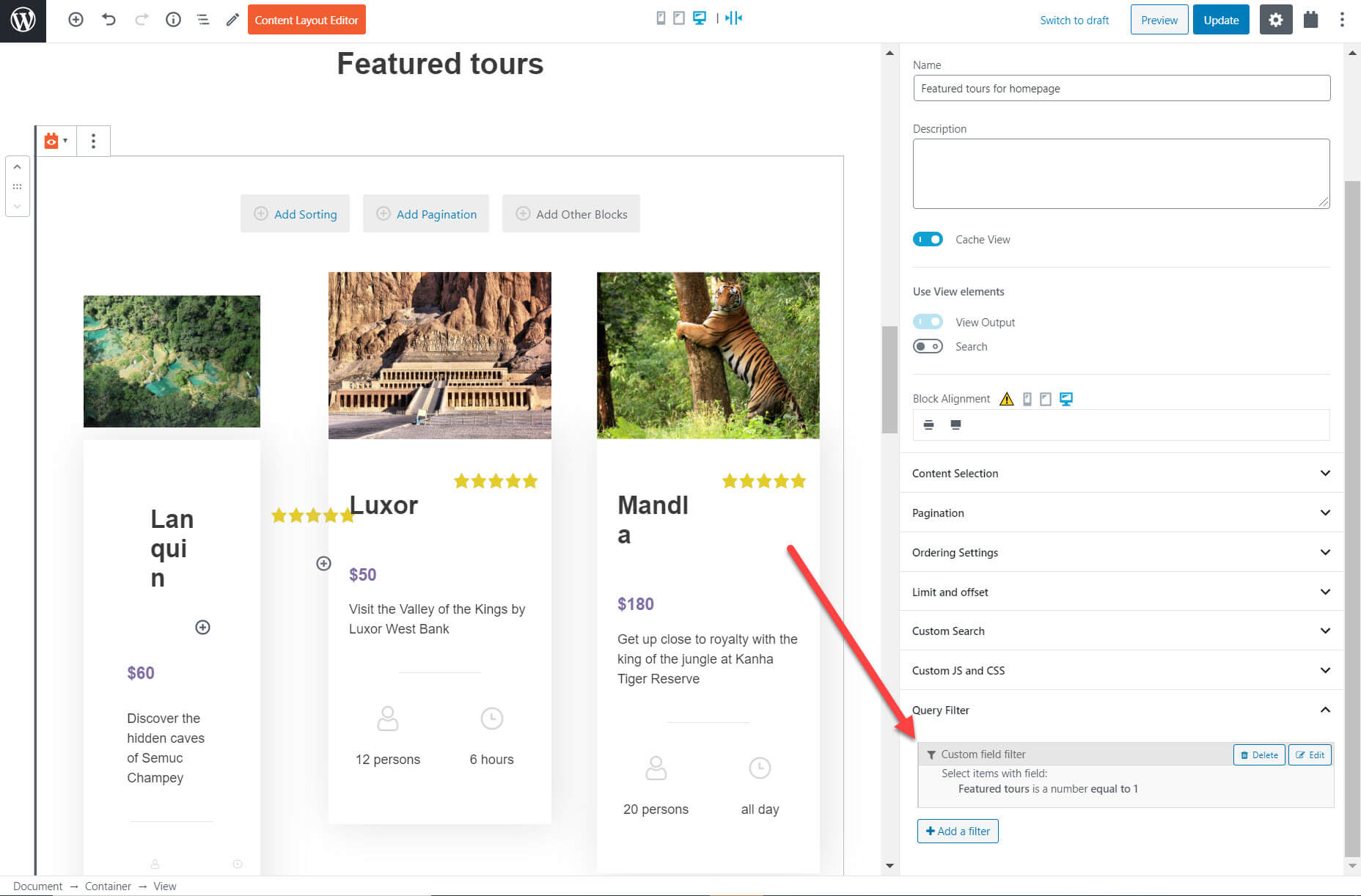

Below for my travel website, I displayed a slider with a list of featured tours. The list includes a number of custom fields including the price, rating and duration.

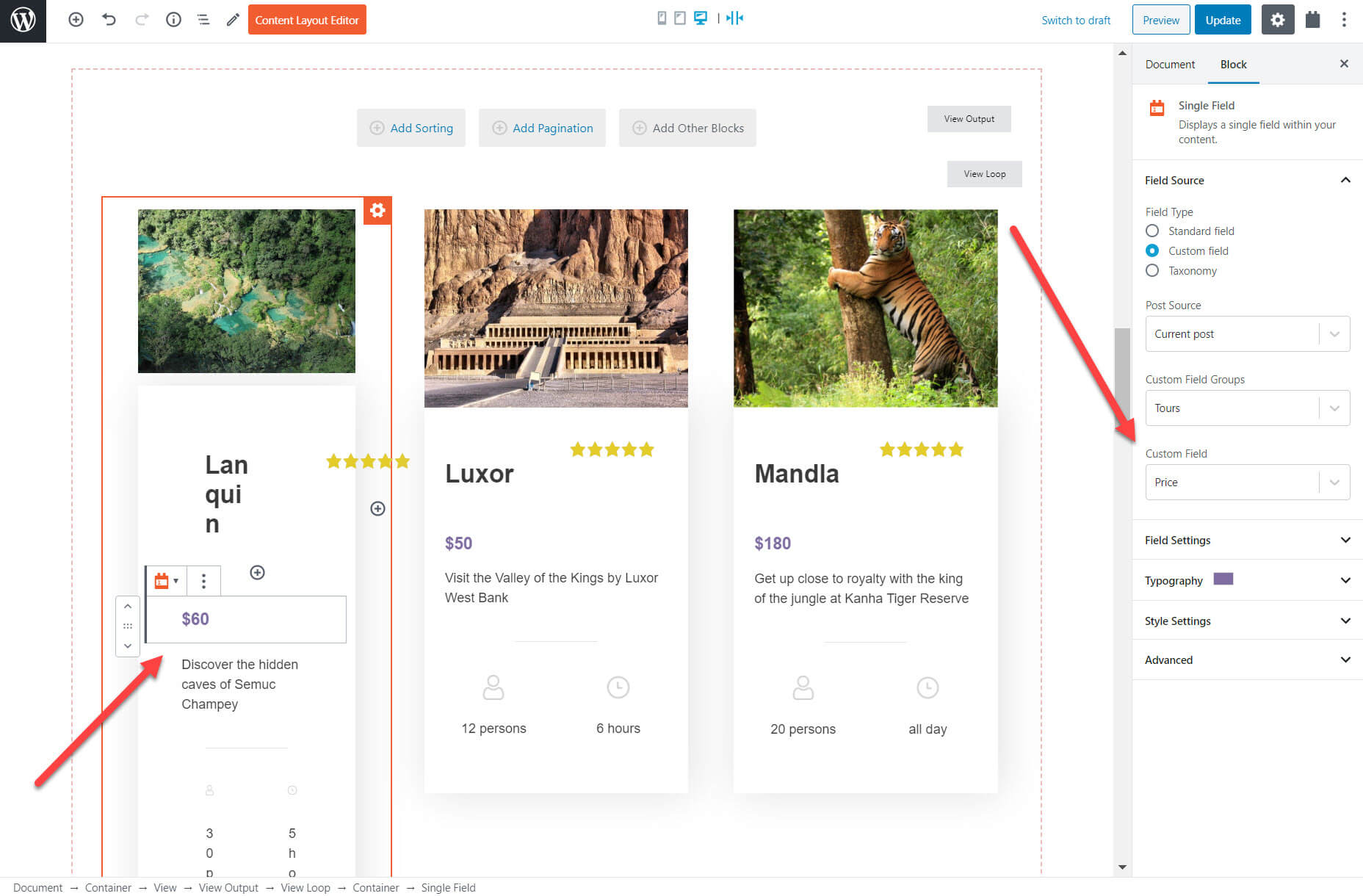

I used Gutenberg and Toolset to create the custom fields which you can see in my list above. Here are all of the custom fields I created. I’ve highlighted the price field as an example.

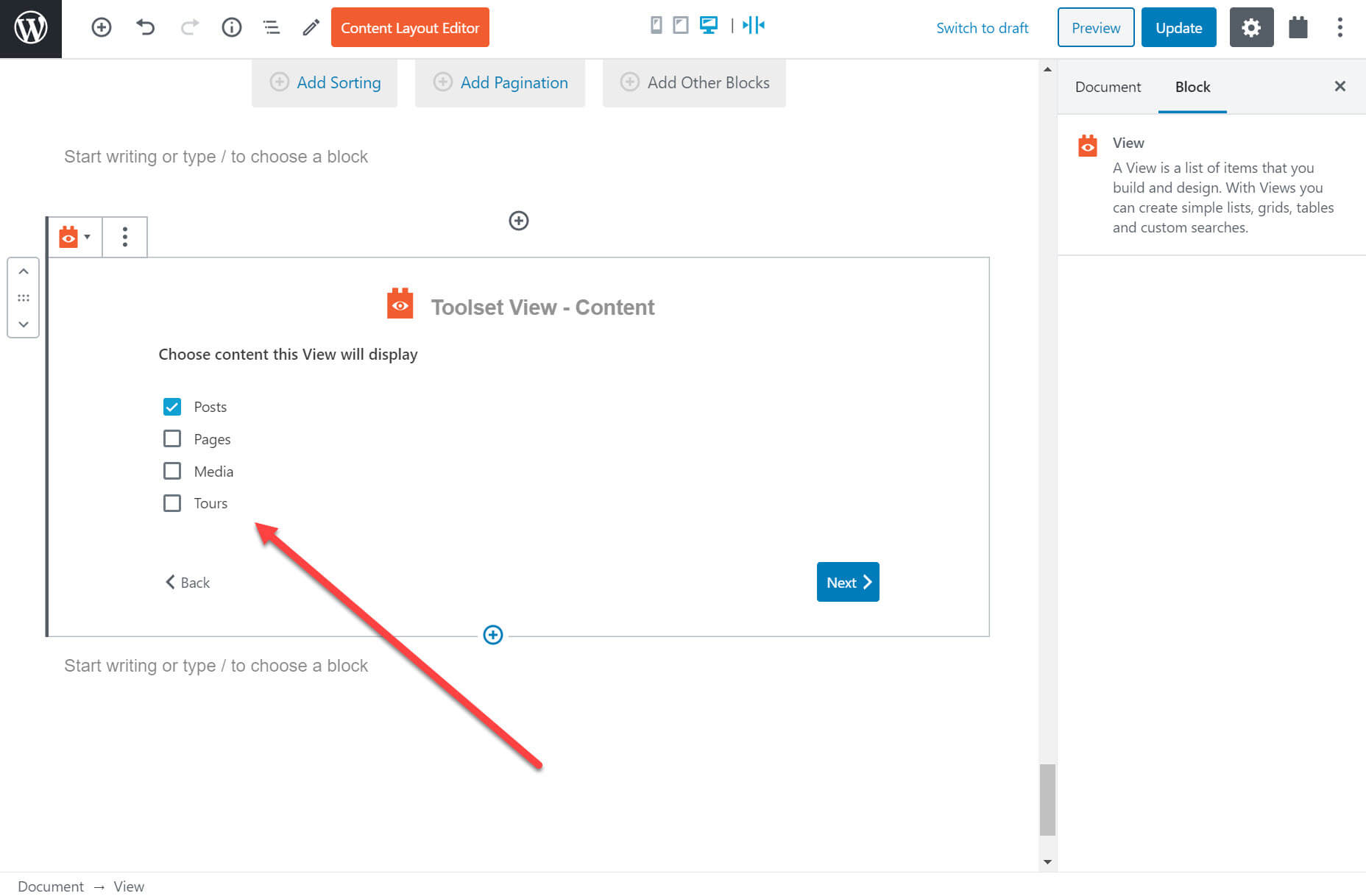

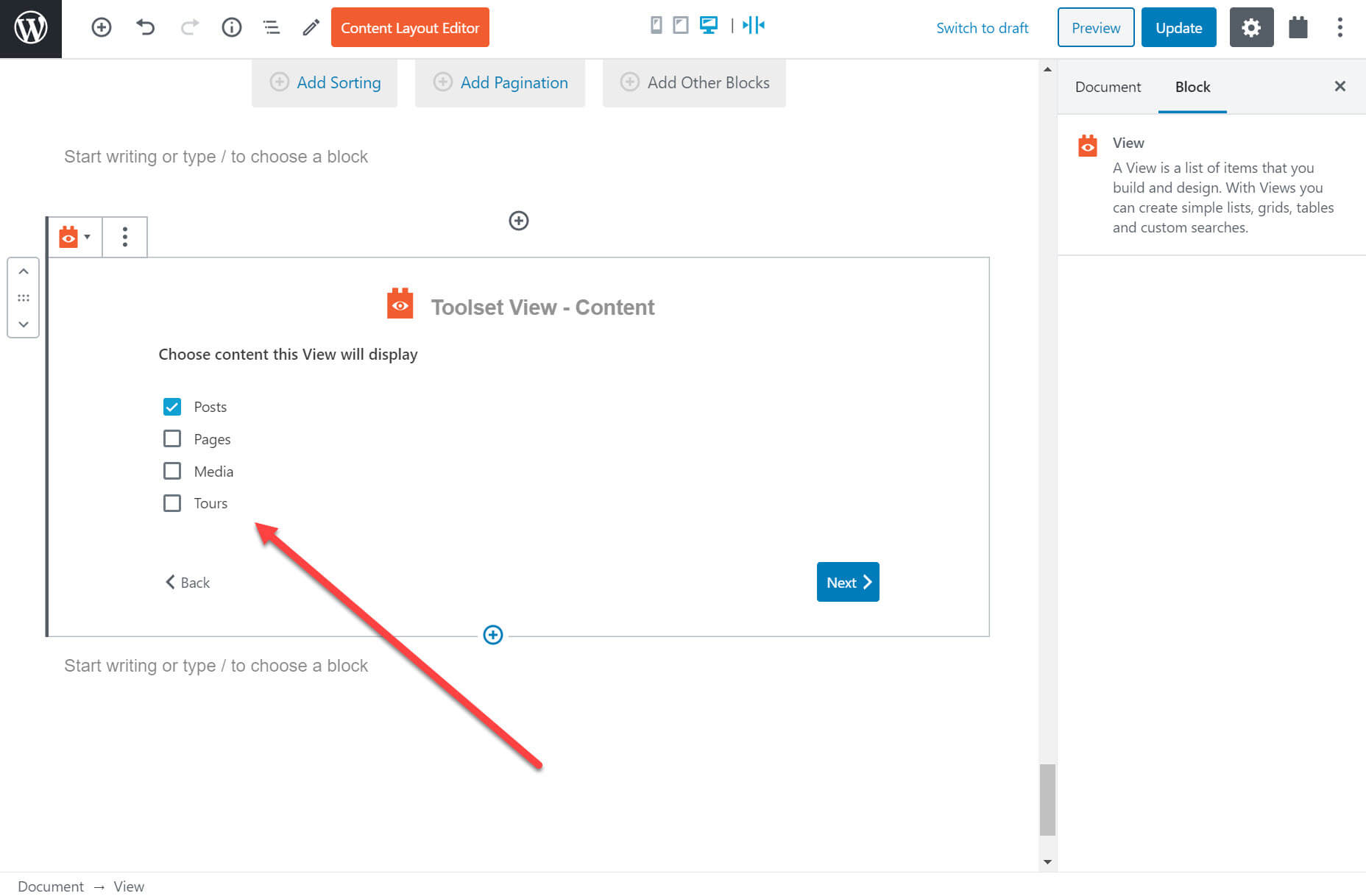

On the back-end I can use Toolset’s View block to create a list of posts. I can choose what posts I want to display and how I want to display them.

For example, below you can see that I am able to select which content I want to display.

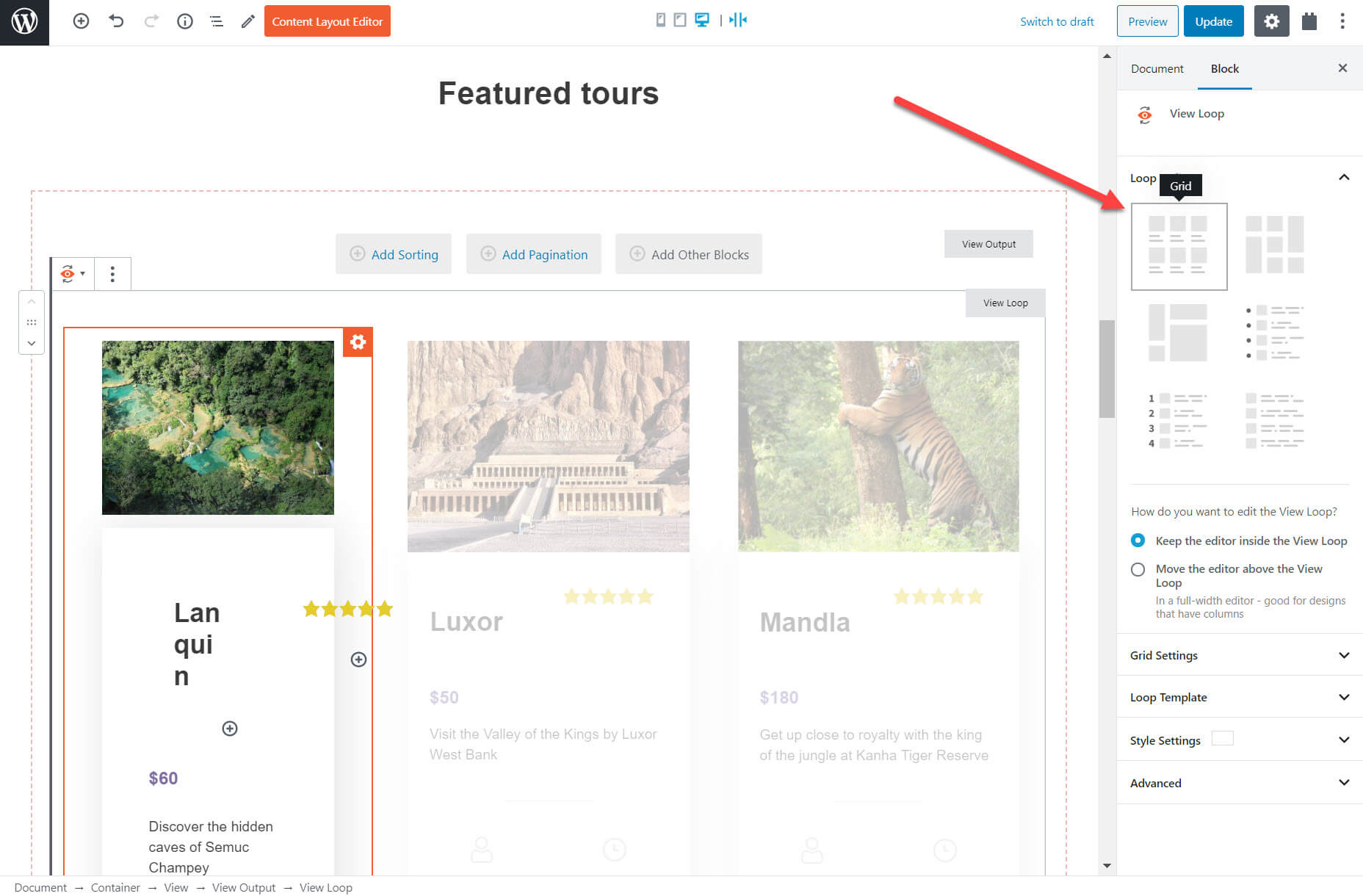

I can also decide how I want to display my list, whether it is in the form of a grid, ordered list, unformatted or much more.

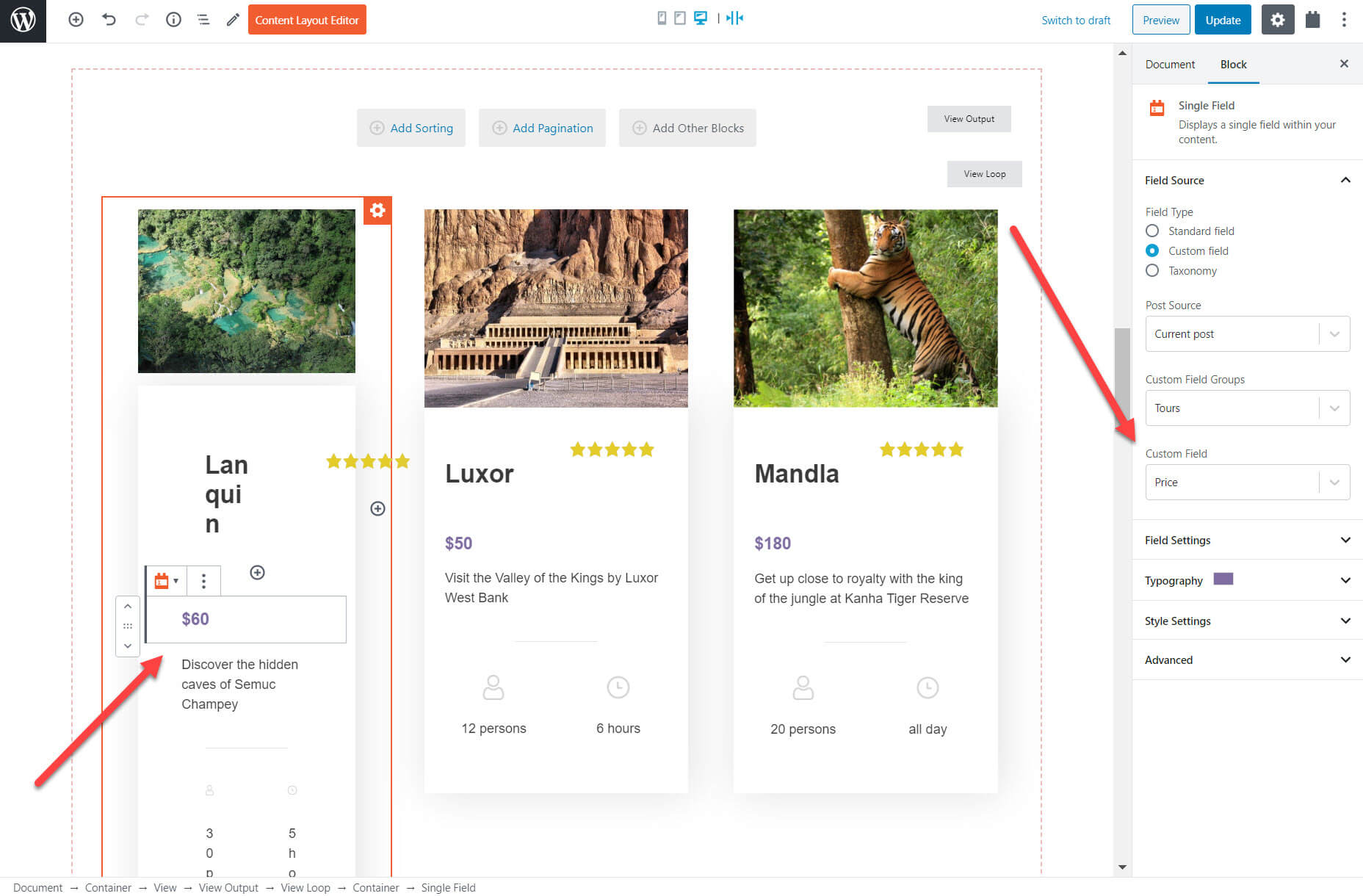

I can now select which fields I want to display. Many of these fields will be the custom fields that I created previously. Each of my tours will display the fields in the same layout. Once again, I’ve highlighted the price custom field below. For each field I create a block and then choose the source of the content (such as the price) on the right hand sidebar.

Once I have arranged the layout for my posts I can decide exactly which posts I display and in what order. Using Gutenberg and Toolset I can select:

The order I display posts such as the most recent blog post;

The number of posts I display;

If I want a filter on my posts, for example display only the tours that cost less than a certain amount.

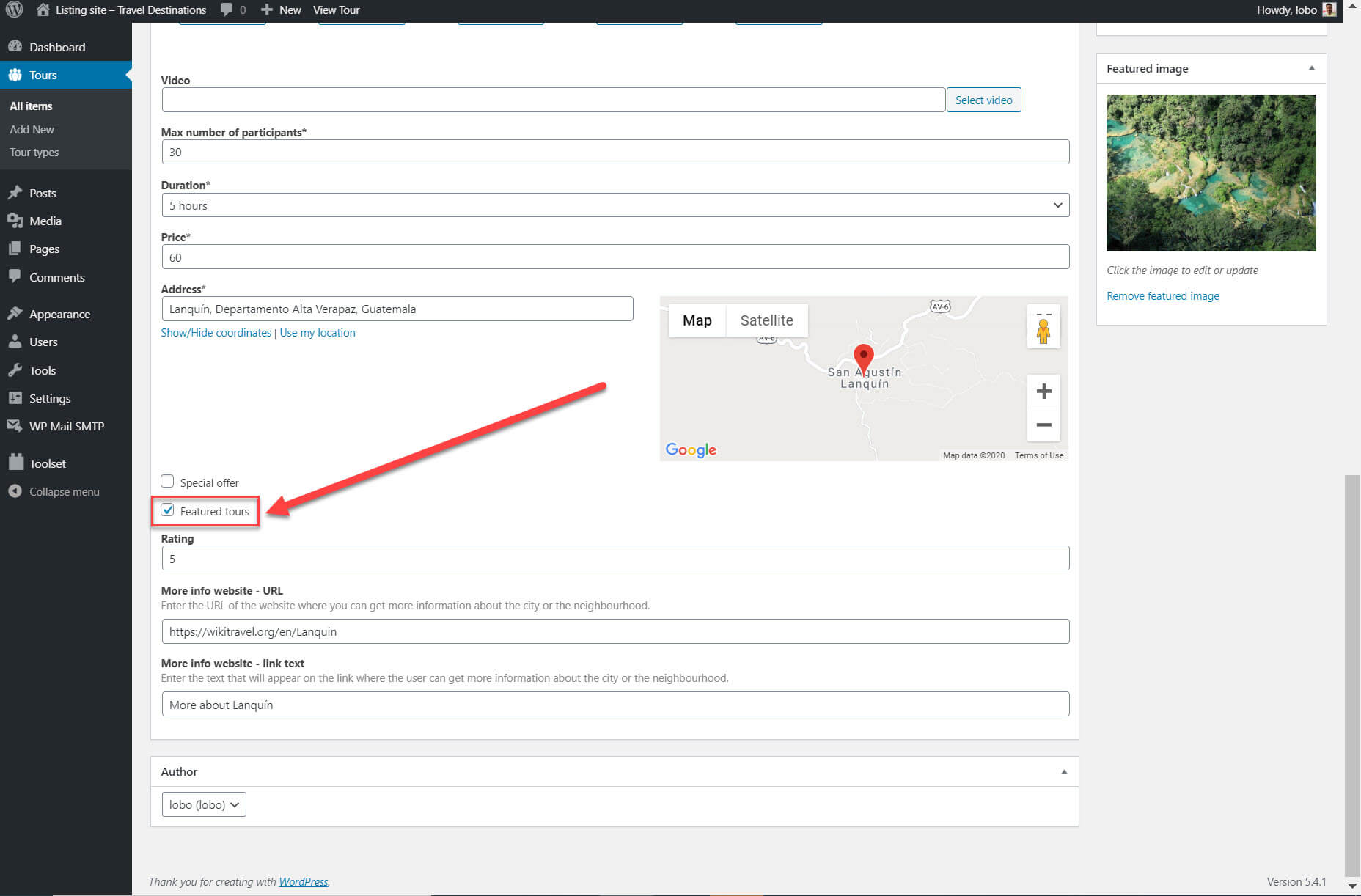

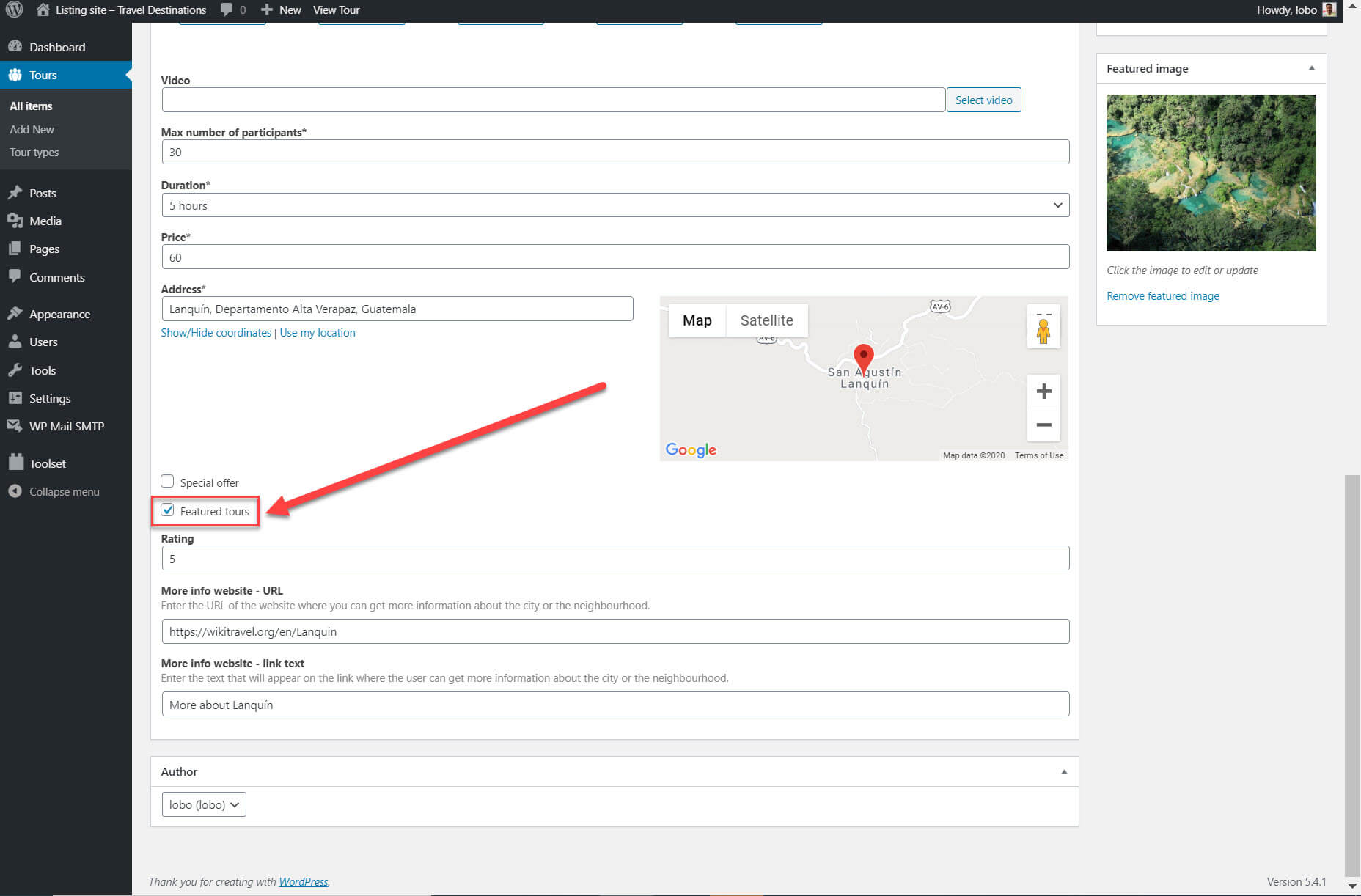

I added a filter to display only the featured tours. As part of my custom fields I created a field for “Featured tours” which you can click for each post on the back-end.

I can use Gutenberg and Toolset to create a filter using the right-hand sidebar which tells my list of content to only display those tours posts which are featured.

Notice how I am able to completely customize my lists of posts on Gutenberg without using any coding at all. Even designers without any programming experience will be able to add a list of posts to their website.

3. Create a Template For Your Content

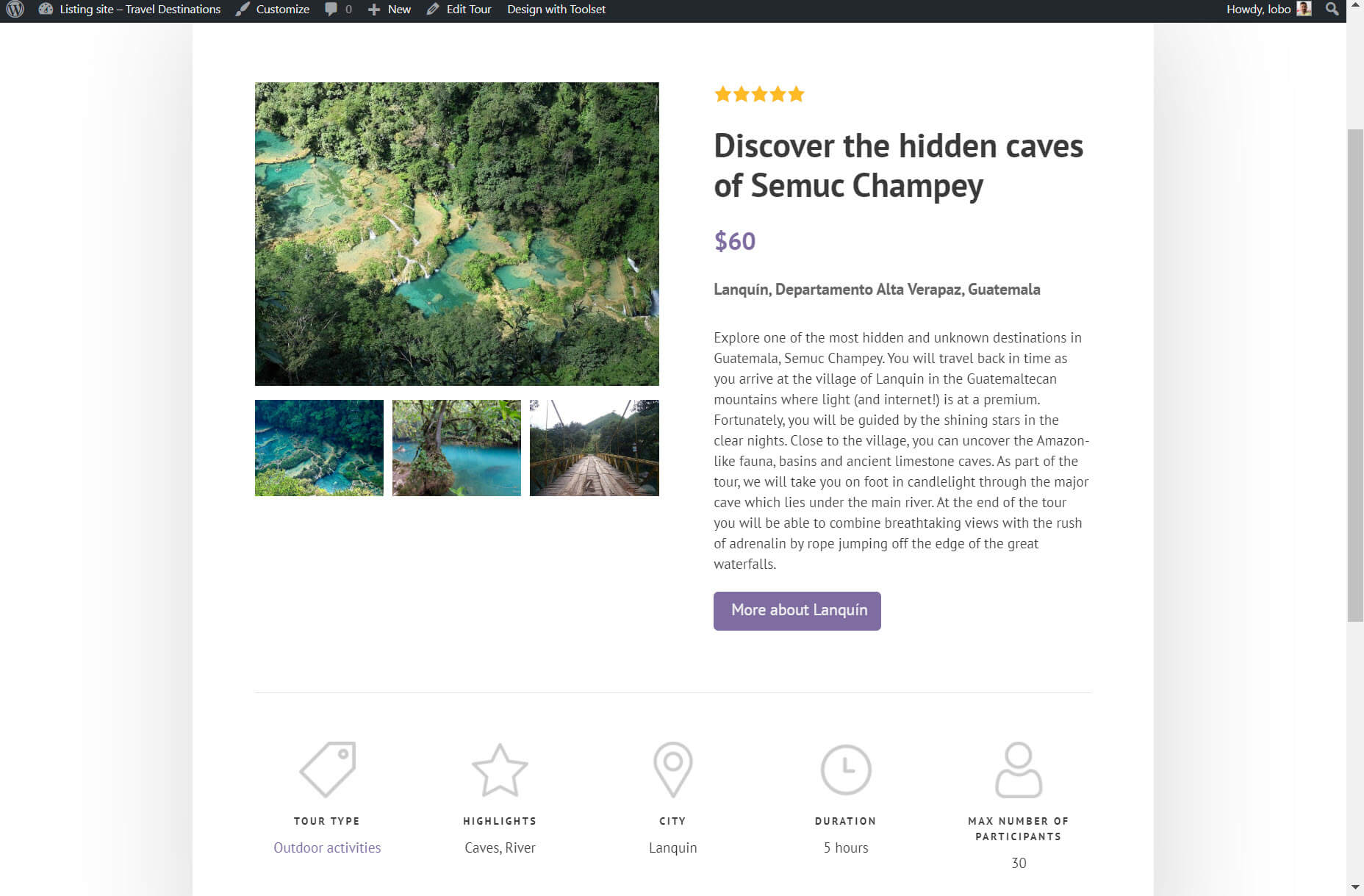

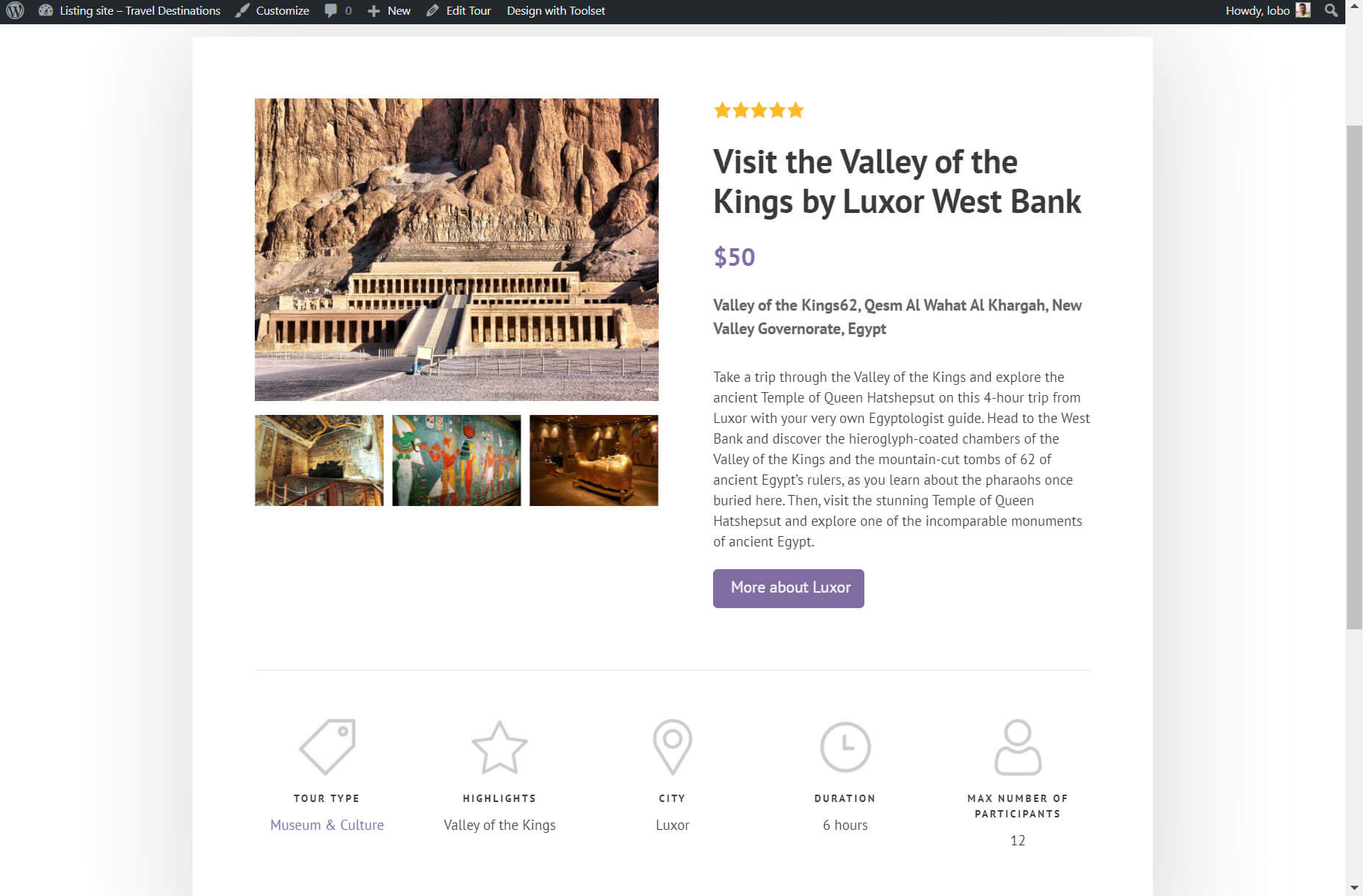

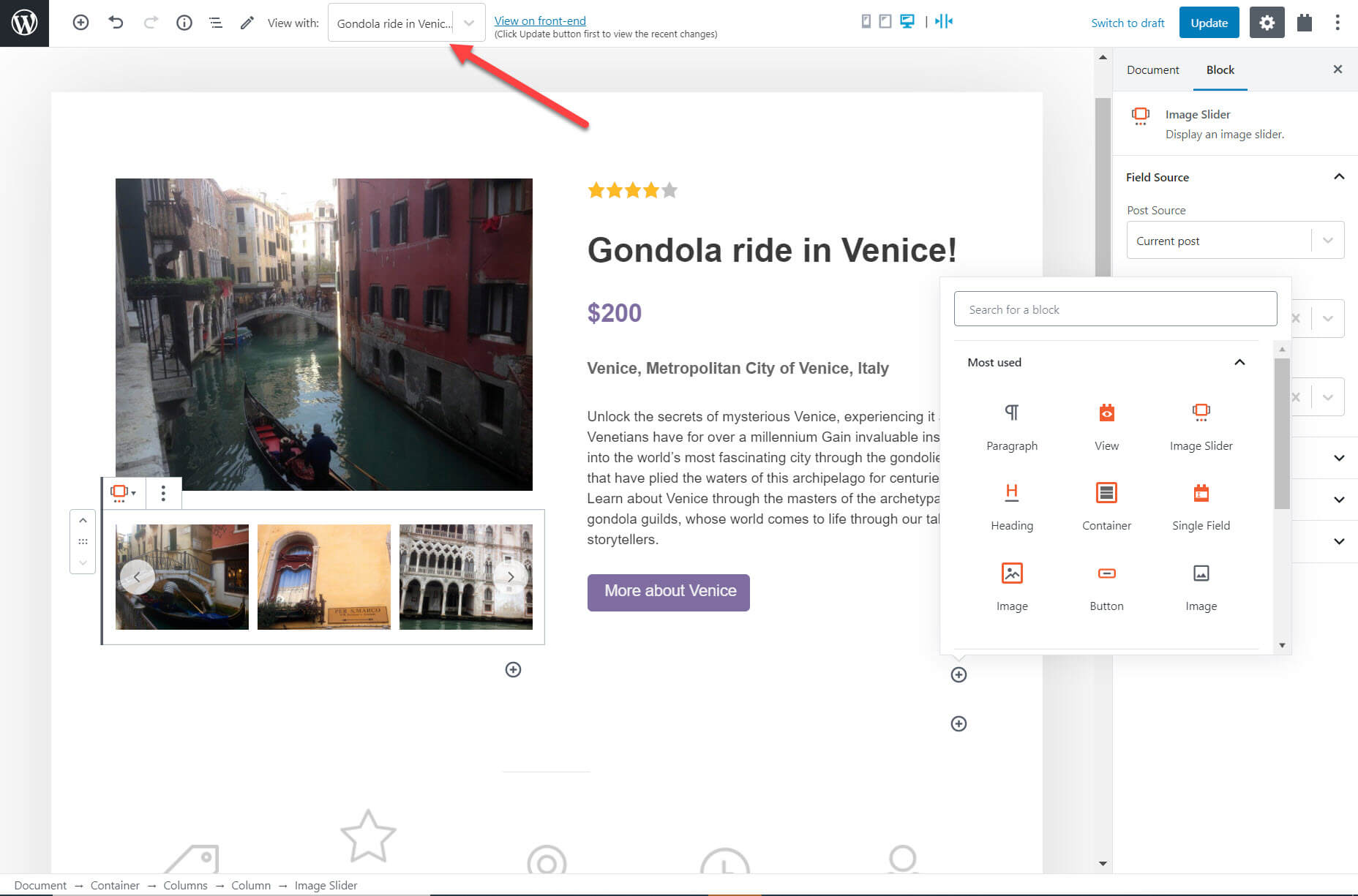

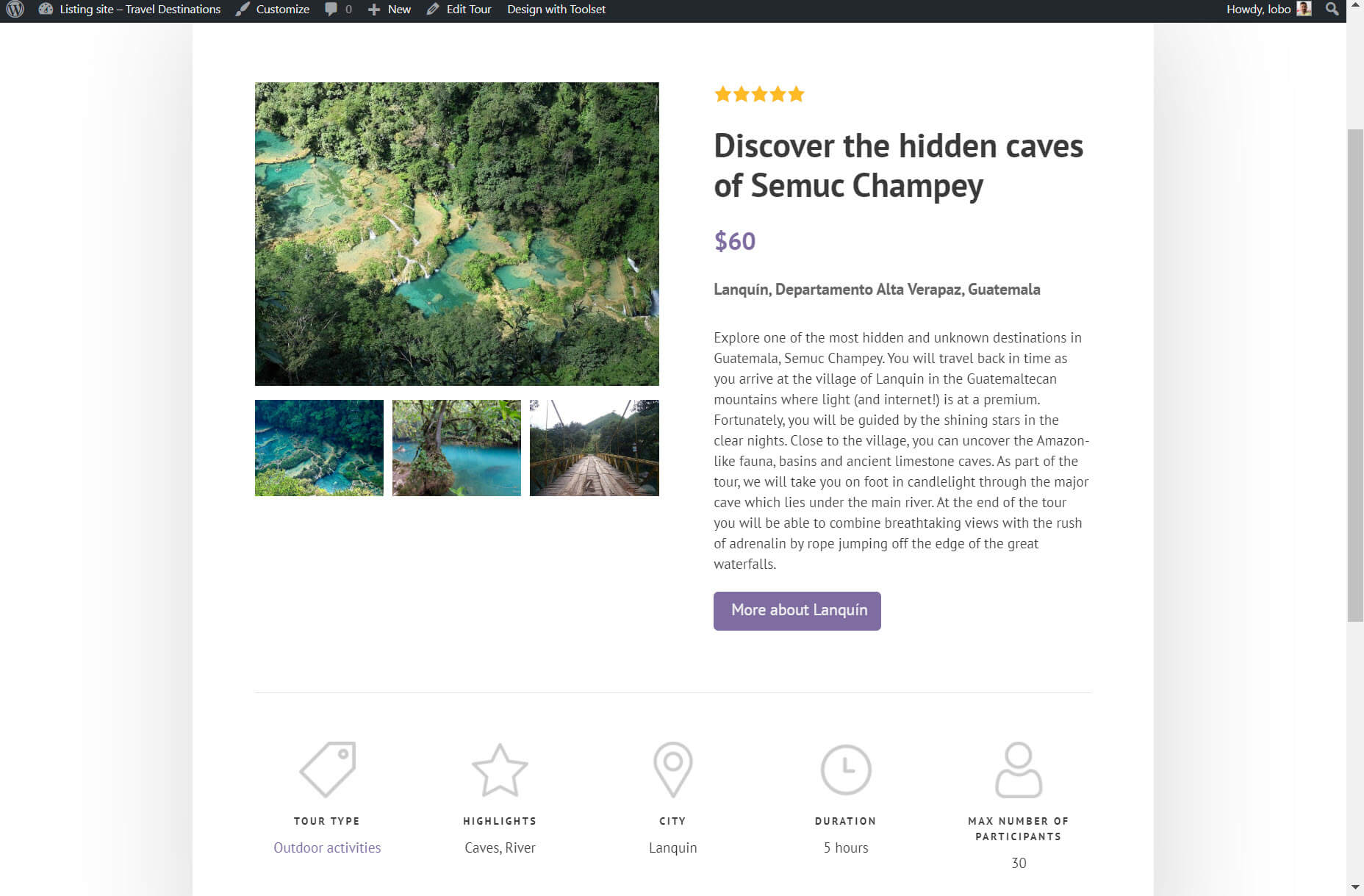

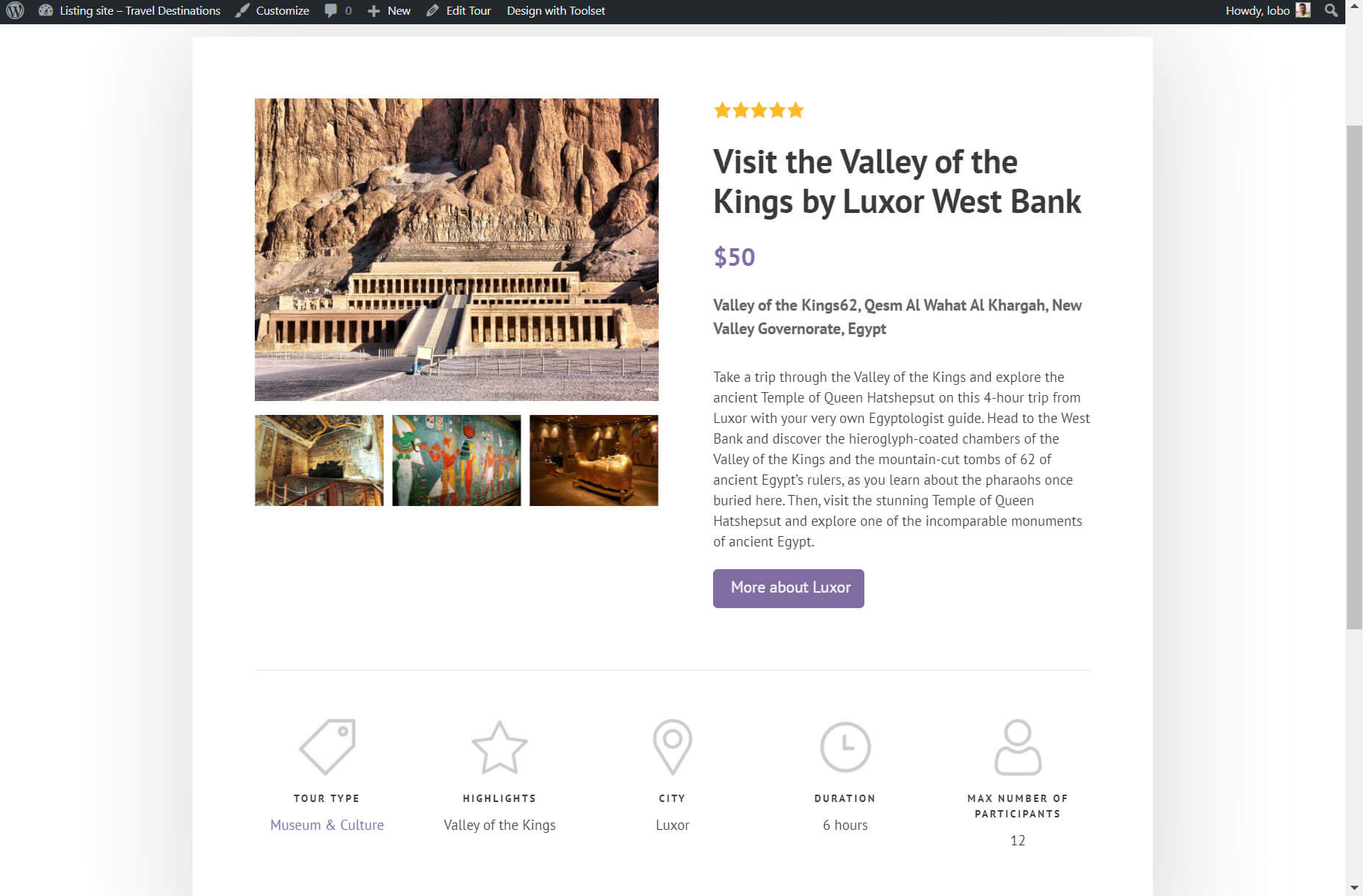

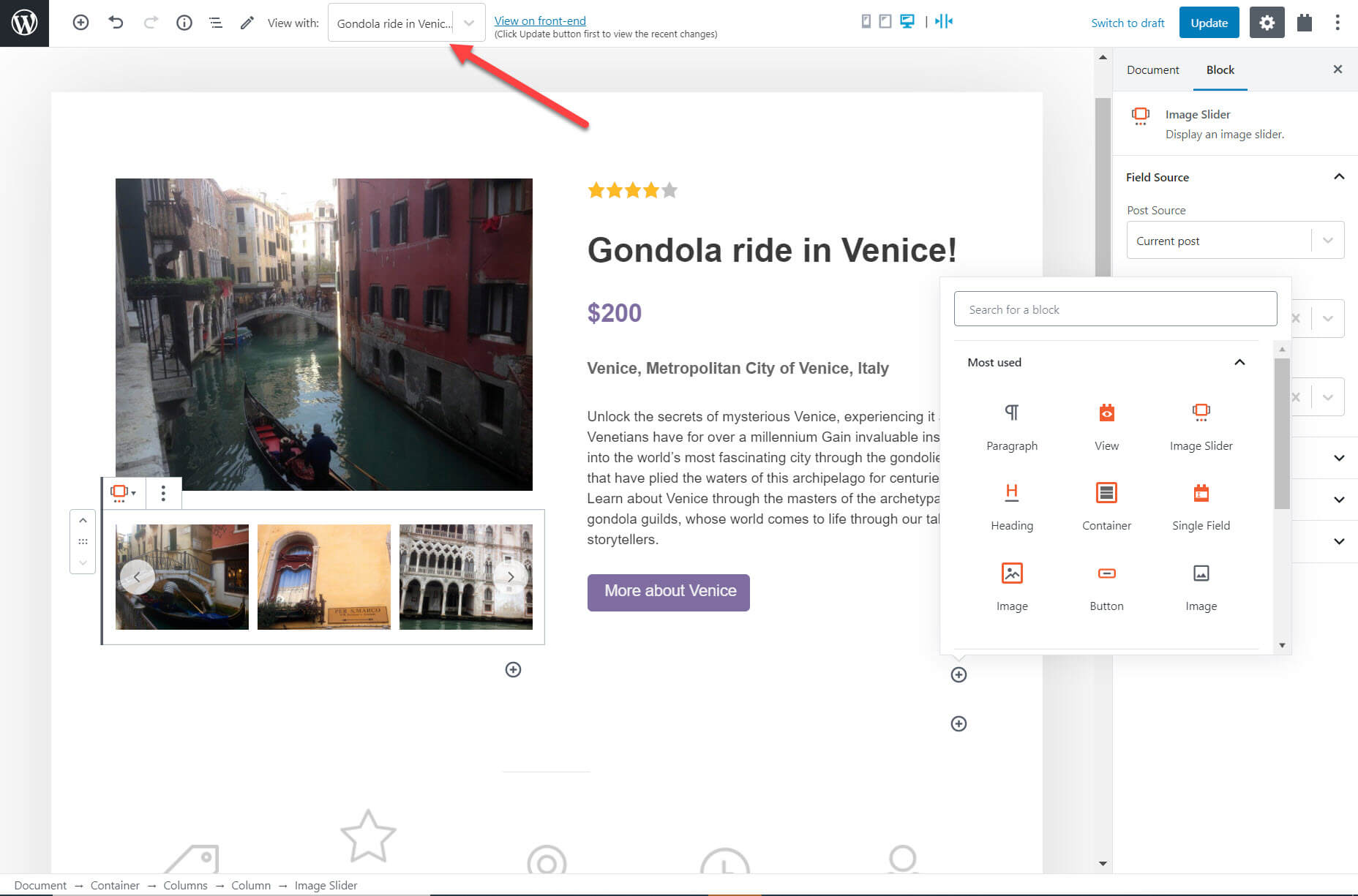

A template is your blueprint for your post types that provides each of your posts with a structure. For example, I’ve created a template for my tours post types which means each tour post will have exactly the same structure when you look at it on the front-end.

As you can see, both posts are from the same template. You know this because each post has the same layout, with the content following the same structure.

All I needed to do to create my template on my Gutenberg Editor was insert my blocks and add dynamic content. As I’m adding the content I can use the drop-down at the top of the page to switch between the posts to see what the template looks like with different post content.

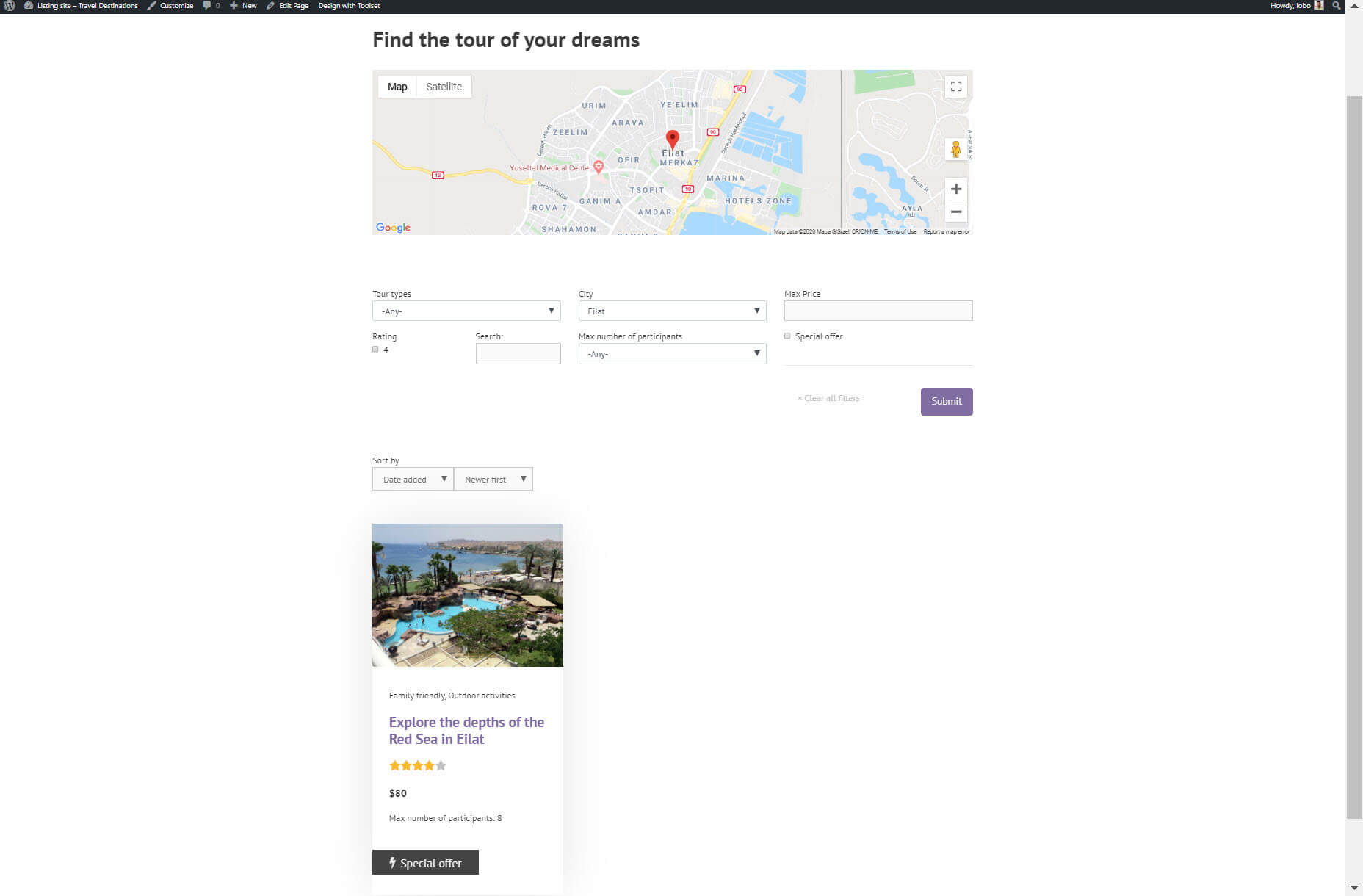

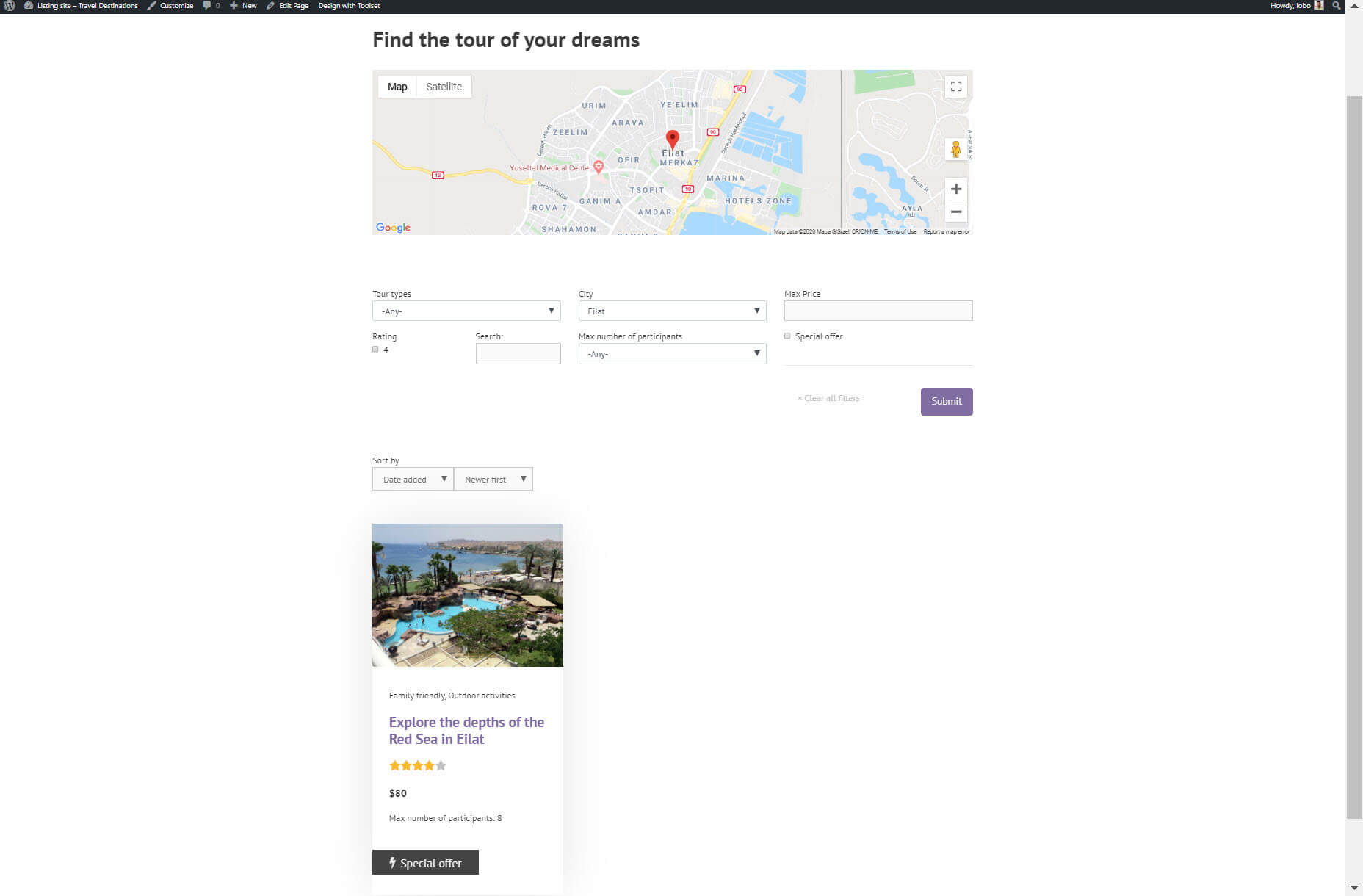

4. Create a Custom Search

One of the most important features on a custom website is a search.

If you are designing a directory website which sells items, for example, you will want to make it as easy as possible for potential customers to find your products. The best way is with a search that contains filters so they can narrow the results down and find exactly what they’re looking for.

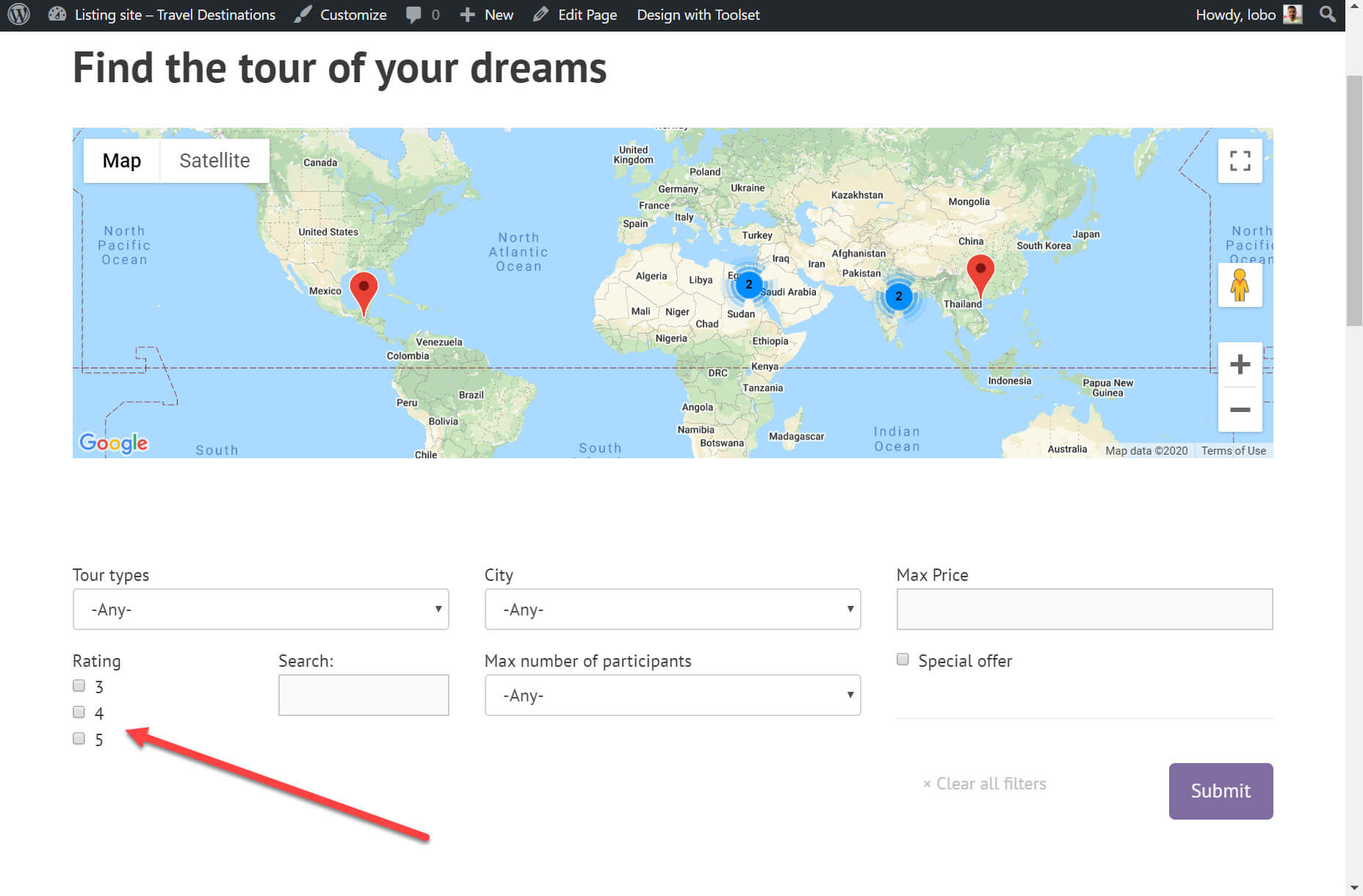

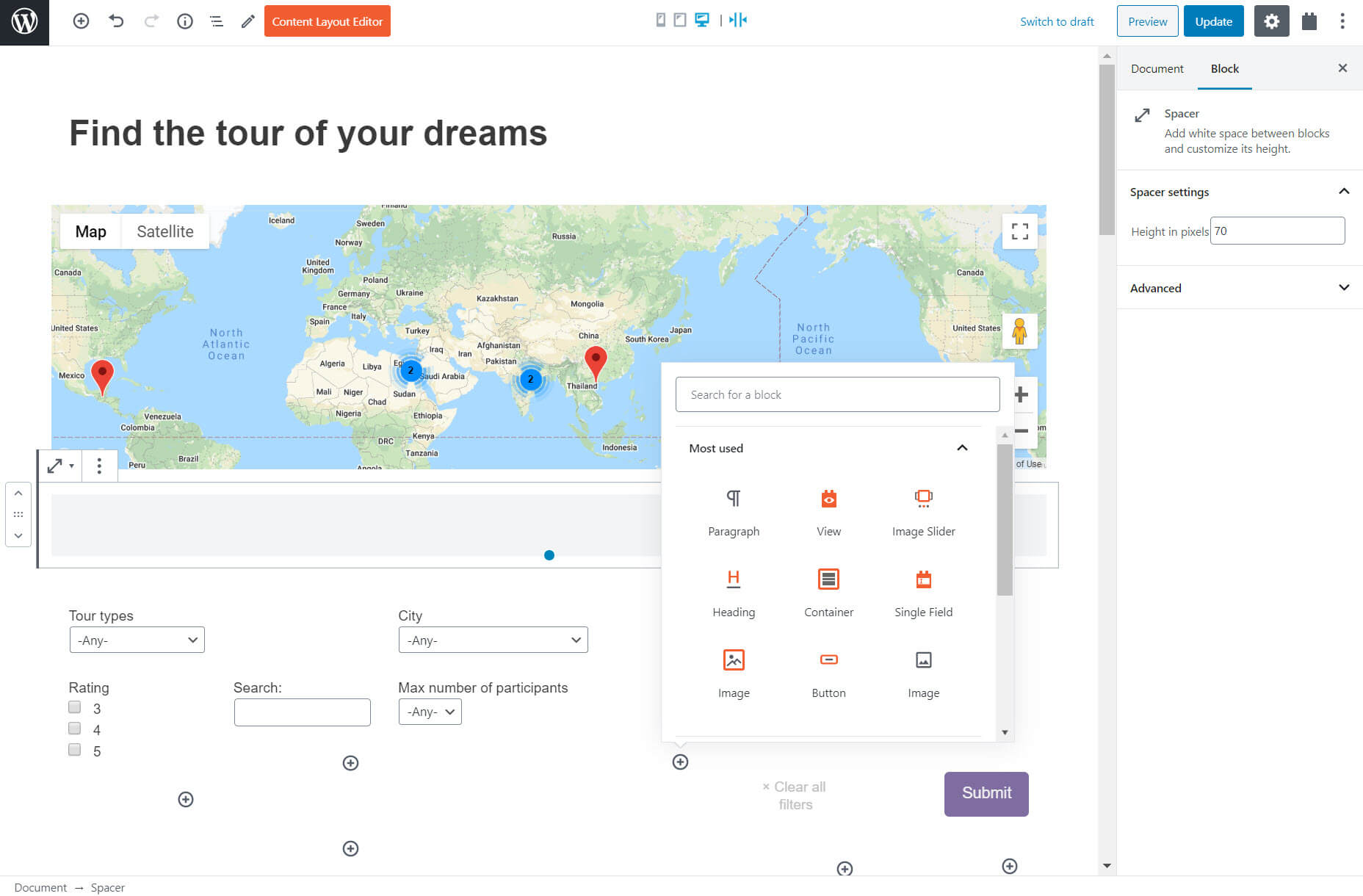

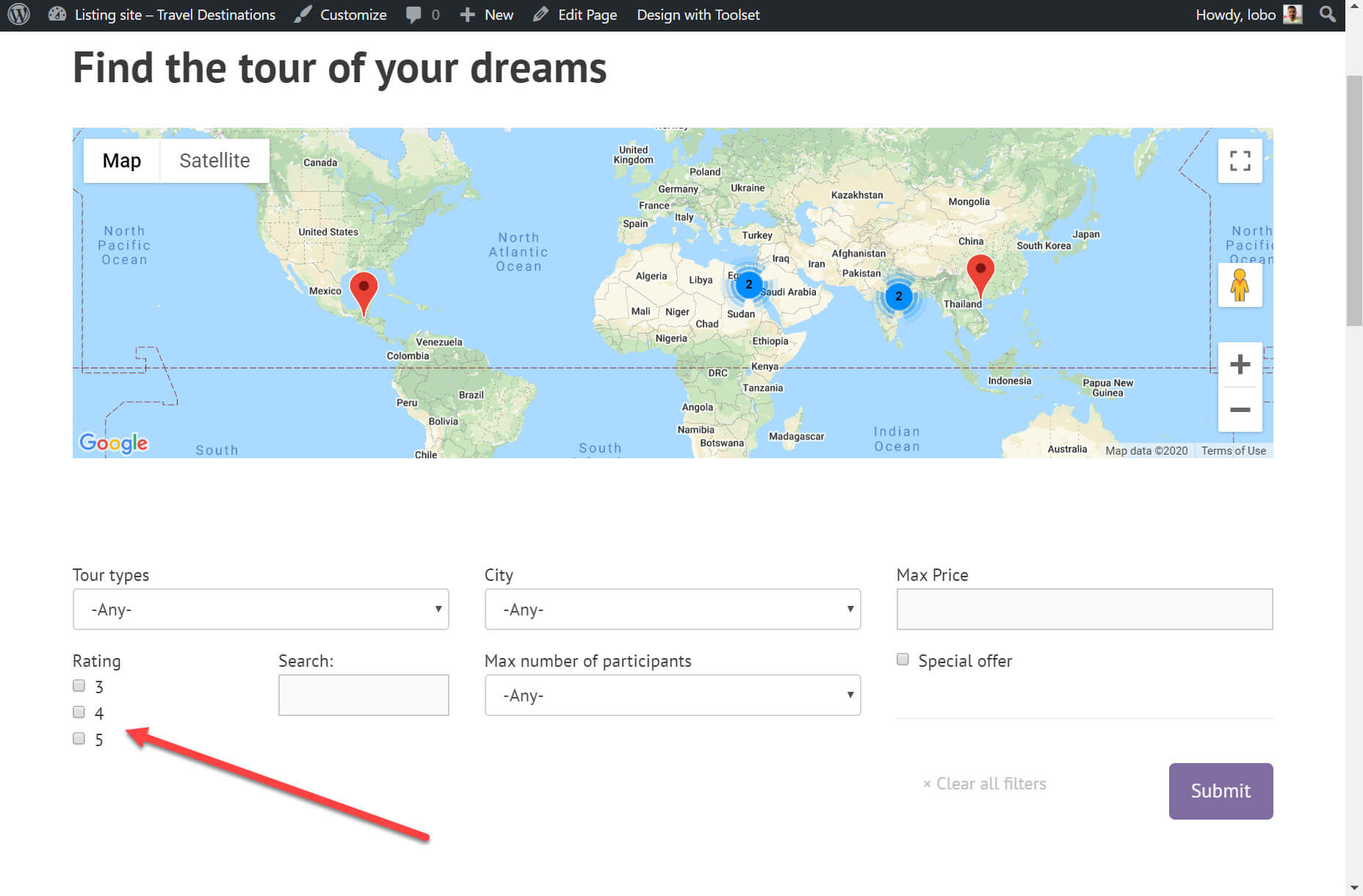

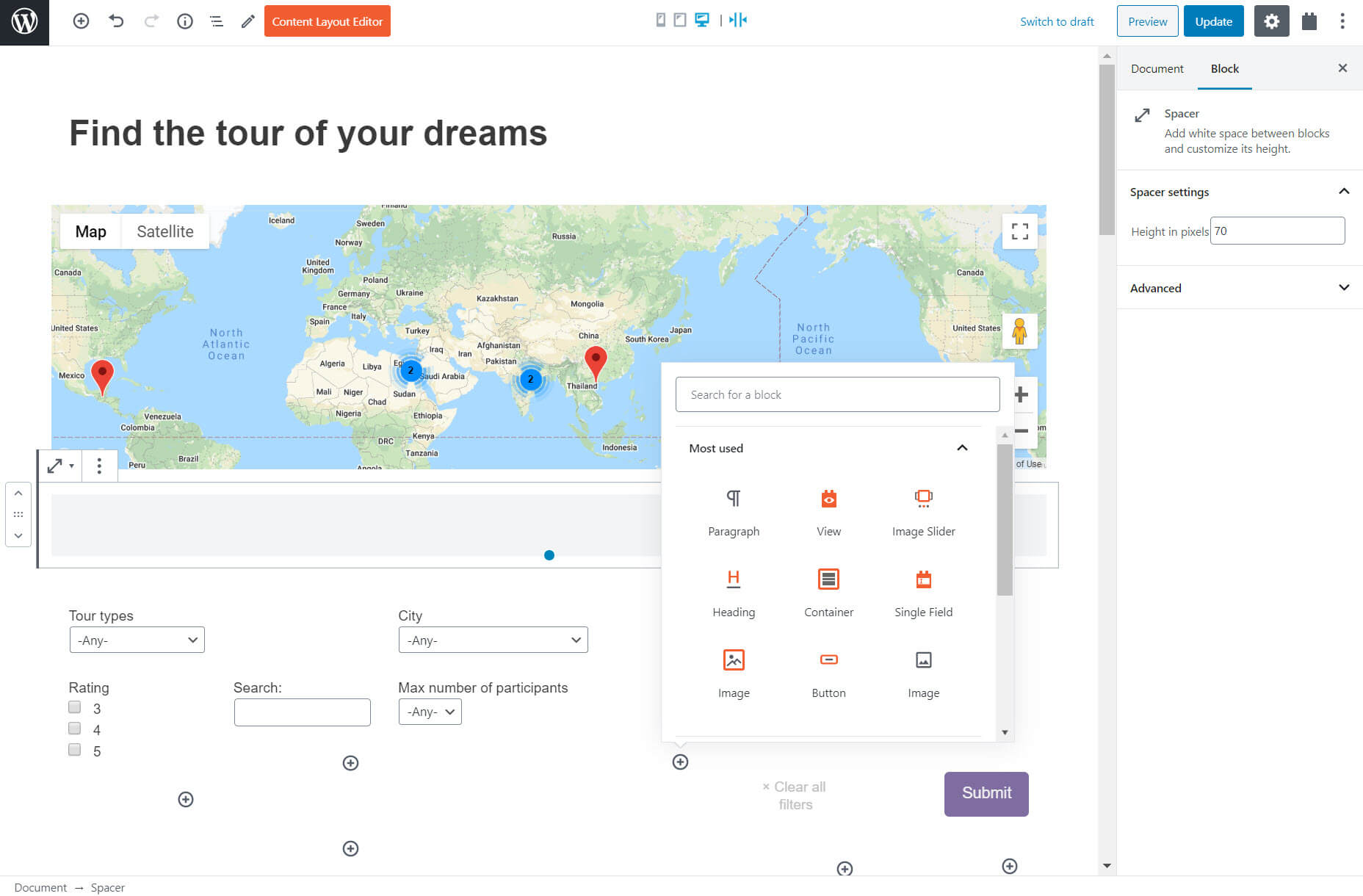

Below you can see the custom search I created using Gutenberg and Toolset for my tours. It contains a number of filters. One of the filters is to only show those tours with a rating of 3-5 stars.

Creating a custom search consists of two steps. First, creating the search (which you can see above) and second, designing the results.

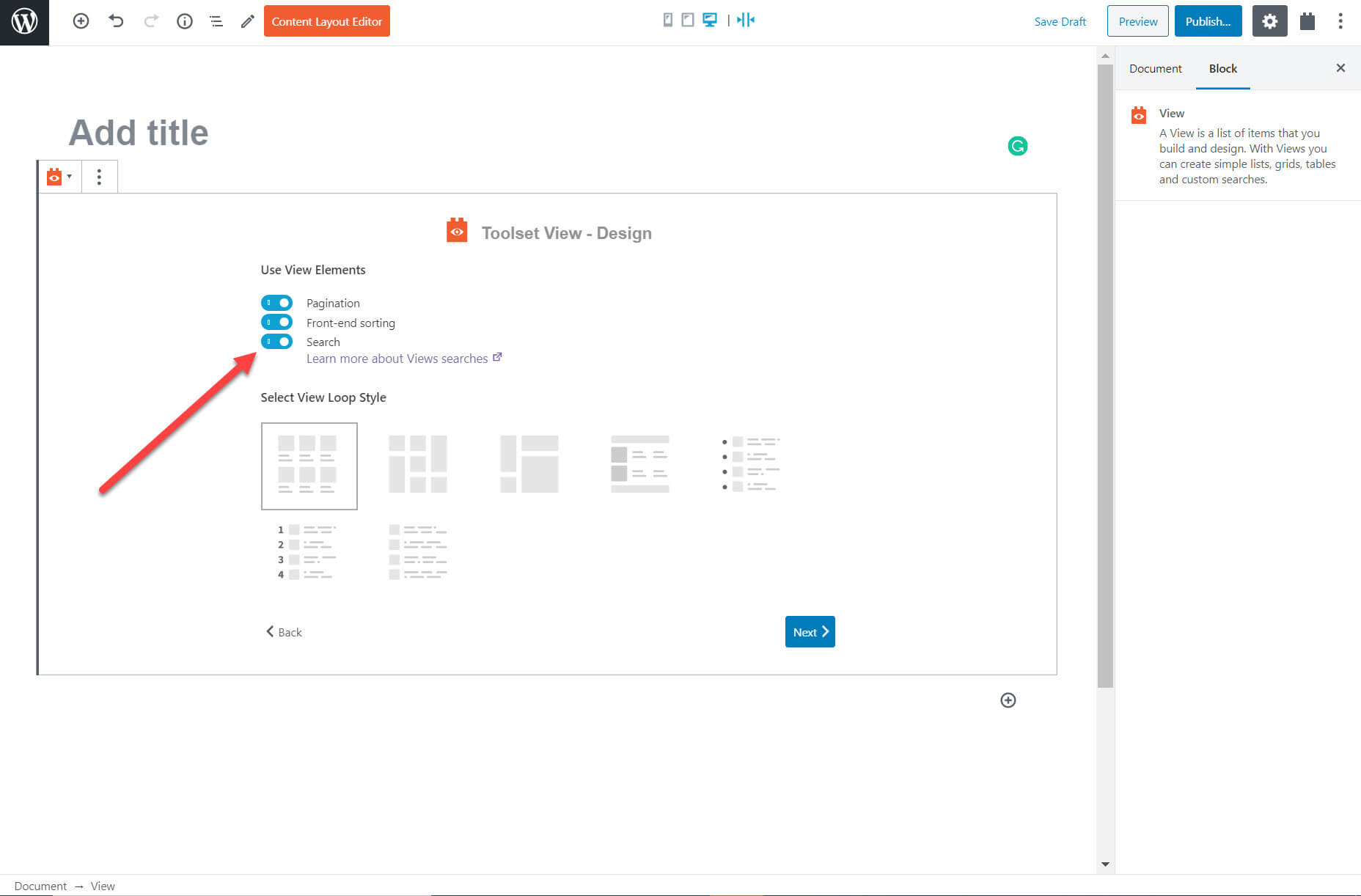

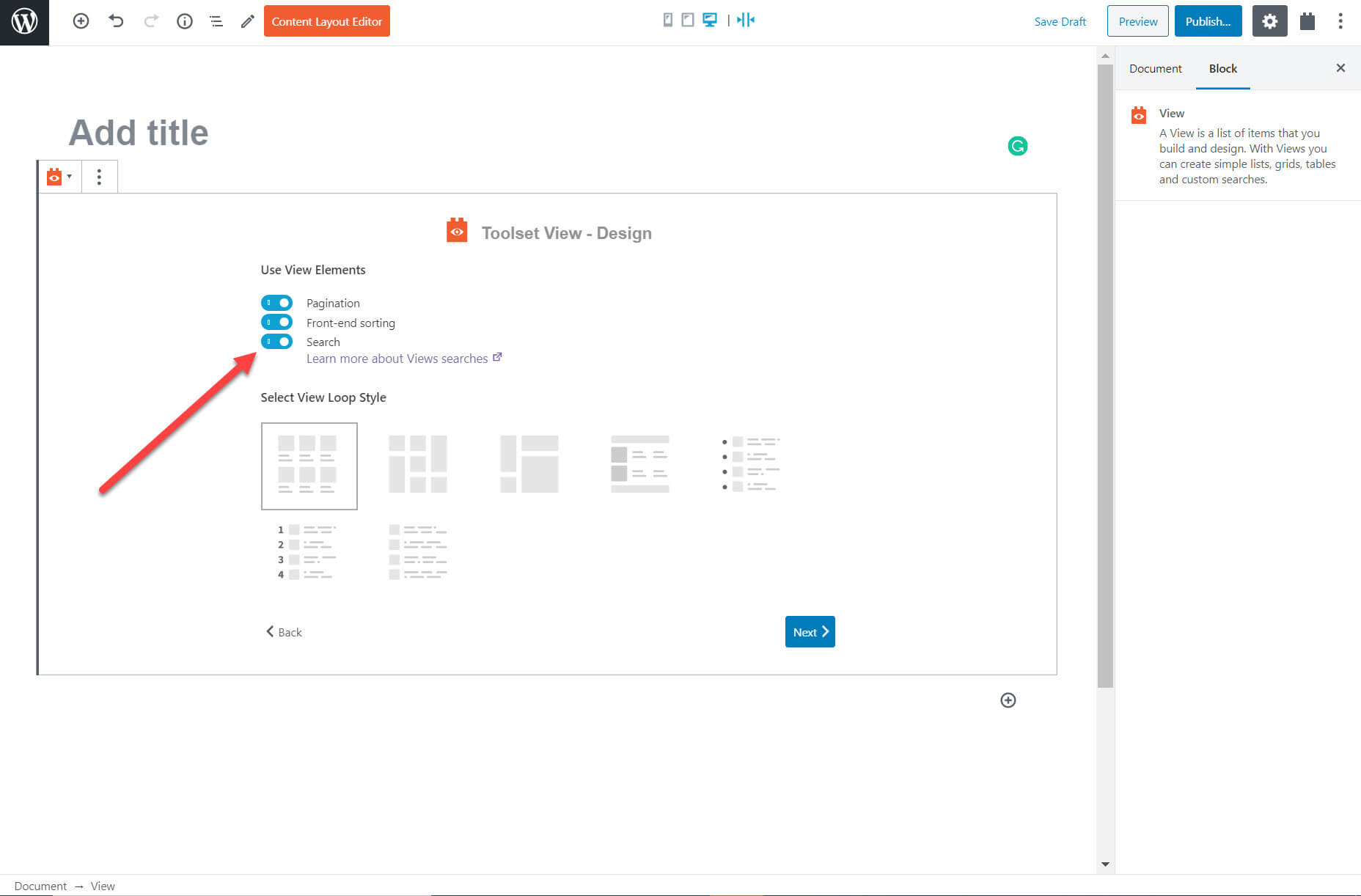

I created the search using Toolset’s View block on a new page. Below are the options to enhance the block. I can select the search option, add front-end sorting so that the user can sort the results when they appear (lowest to highest price, for example) and pagination to split the content into pages.

Once I add the block I can proceed to add additional filters such as the maximum price. I can also include a map and markers to display the results. Once again thanks to Gutenberg and its extensions I do not need to use coding. I just select the blocks and adjust the options on the right-hand sidebar.

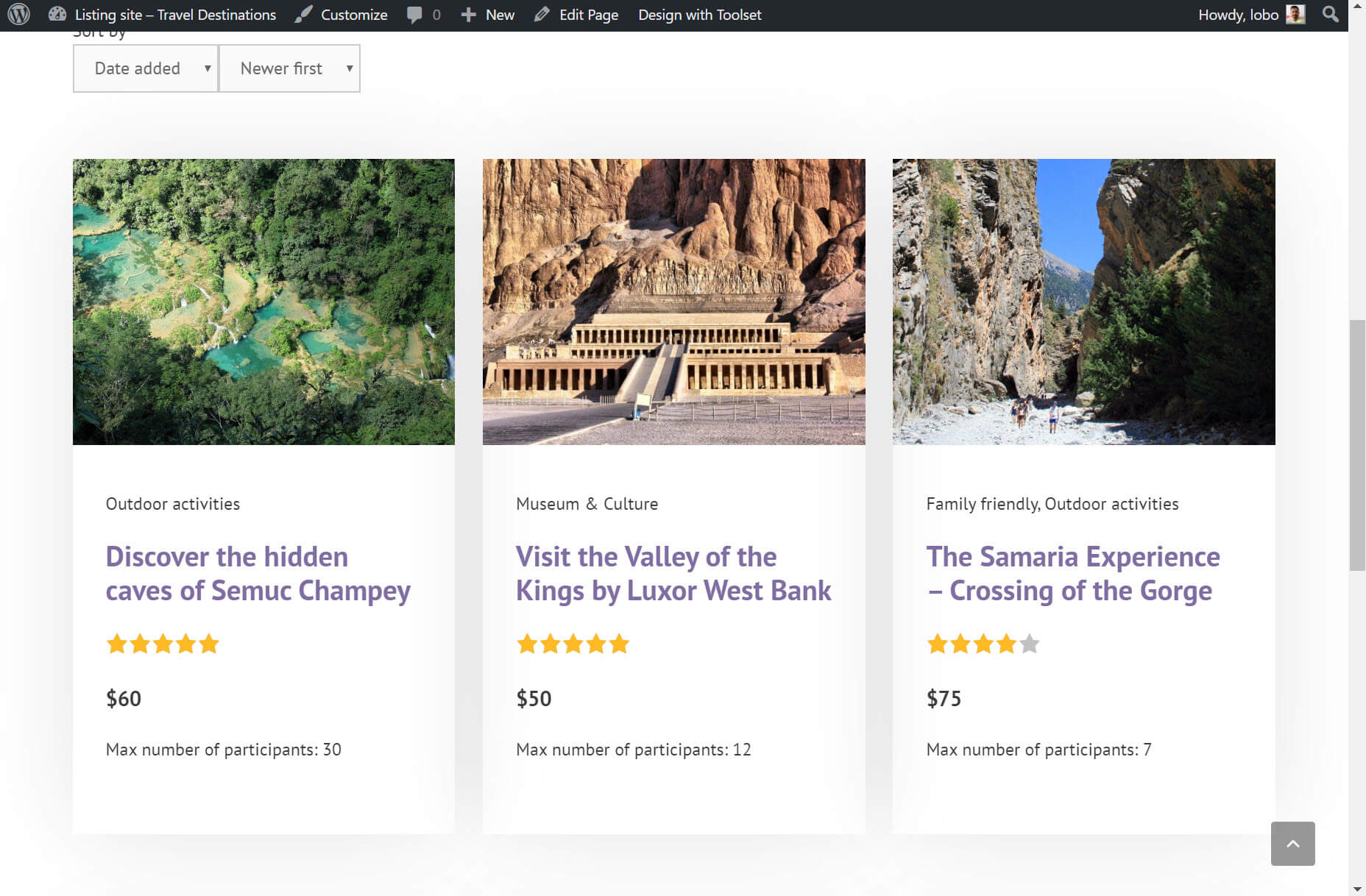

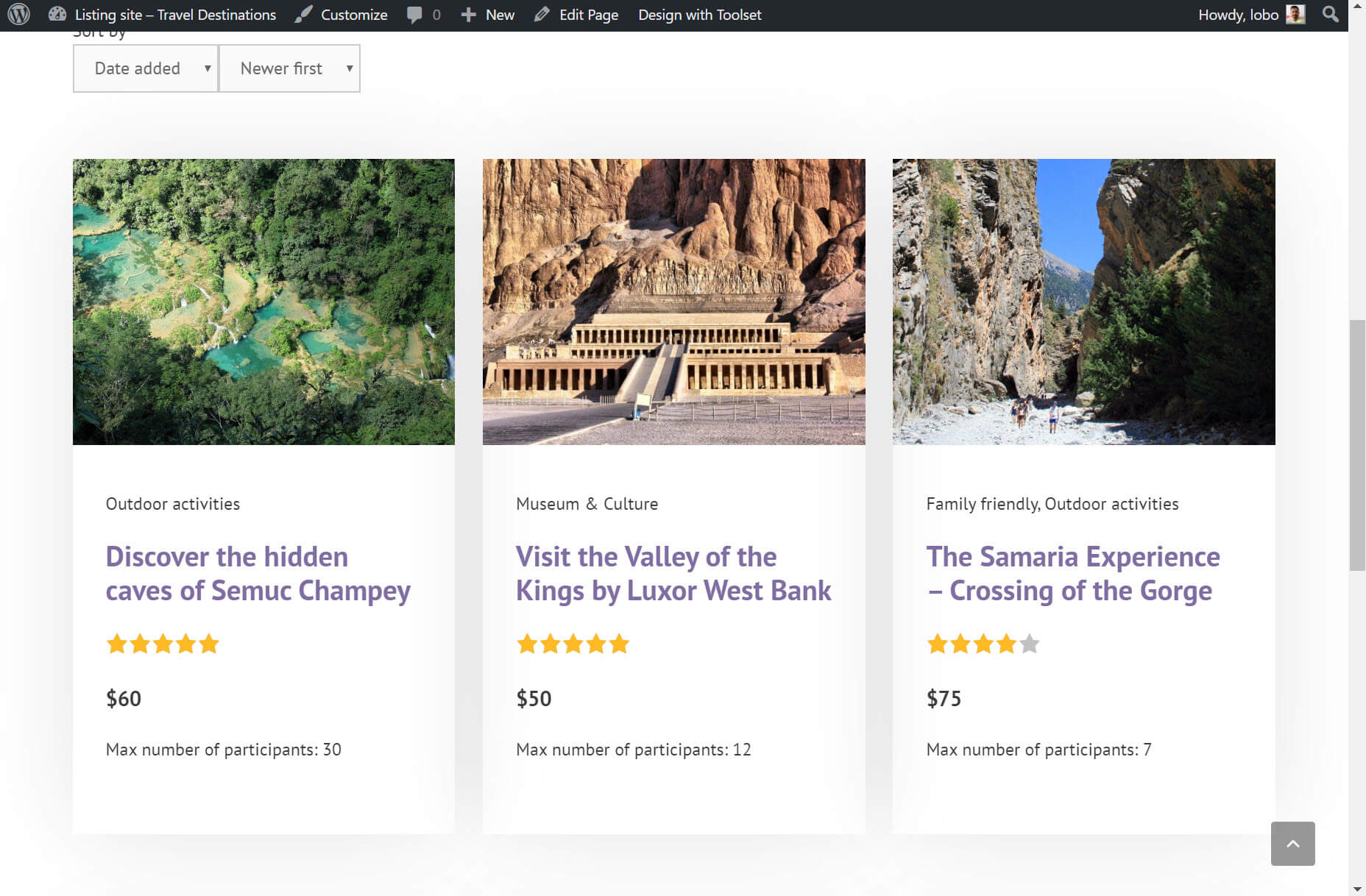

For the results, I added blocks just like I did for the template and custom list of content.

And just like that, I have a custom search for my tours. I can now enter searches using the filters on the front-end.

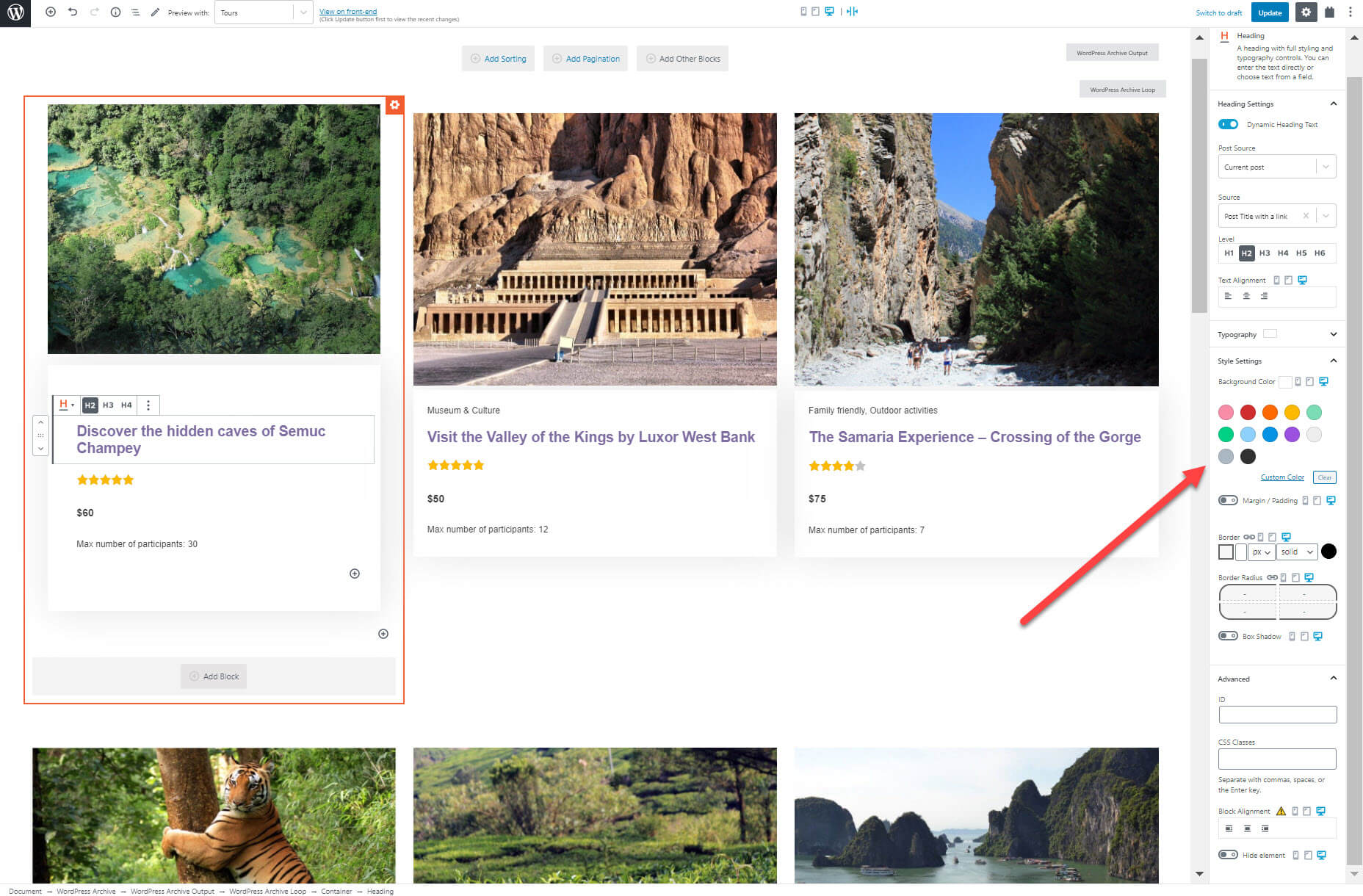

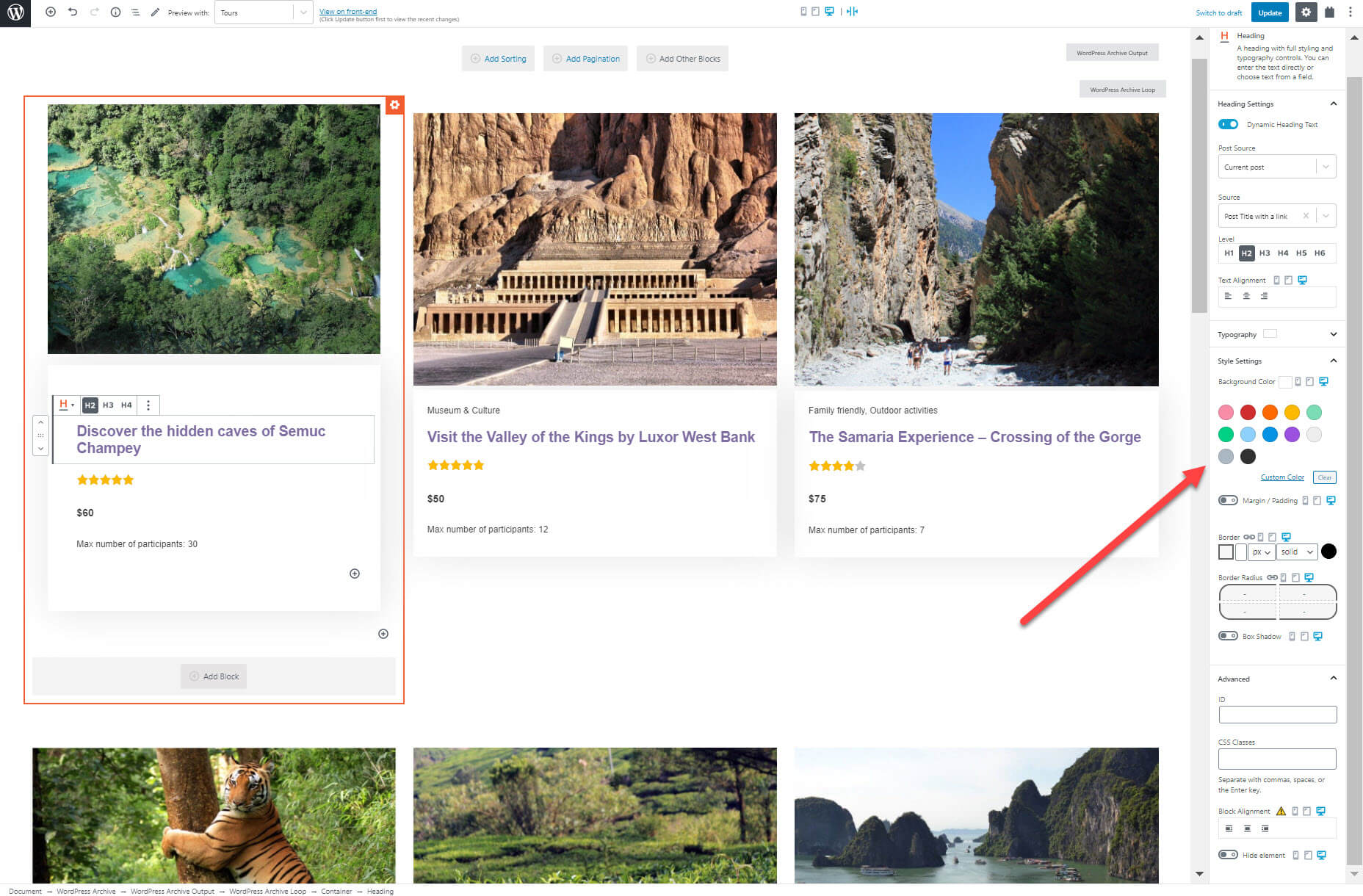

5. Create an Archive of Similar Posts

An archive makes it easier for users to find all the posts you have published. If you want an archive with standard fields such as a heading and post content then a page builder such as Elementor is a great option. However, if you want to include custom fields with dynamic content then you will need to use Gutenberg,

I built an archive for all of my tours on my travel website. When someone clicks on the archive they will see every tour I have created. You can create a tour for any of your posts.

Just like with the custom list of content I can add the blocks for the content and arrange the posts how I want.

I can also style the blocks by changing the text color, adding a padding/margin, add the background color, and much more.

You Do Not Need to be a Professional Developer to Create Professional Websites

Now that you have seen how even a coding beginner can build complete custom websites it is time for you to try it out yourself. Here are some tutorials and documentation worth going through:

If you are new to Gutenberg, Colorlib offers a good WordPress Gutenberg tutorial which will introduce you to how you can create blocks.

The plugin I used with Gutenberg, Toolset, offers a training course on how you can use the two tools to build WordPress directory websites. It is a great way to understand exactly what features you can build and how for any type of website.

To keep up to date with any changes to Gutenberg it is also worth keeping an eye on the block editor handbook.

Gutenberg is still in its infancy and is far from the finished product. But that does not mean it can’t revolutionize the website building contracts you can take on. If you take advantage of its visual UI and blocks plugins you will be able to build custom websites that you never before thought were possible.

Source

p img {display:inline-block; margin-right:10px;}

.alignleft {float:left;}

p.showcase {clear:both;}

body#browserfriendly p, body#podcast p, div#emailbody p{margin:0;}

Web designers could be forgiven if their eyes glazed over at the mere mention of building a custom website. Creating an advanced website used to require programming knowledge and hours of coding.

Web designers could be forgiven if their eyes glazed over at the mere mention of building a custom website. Creating an advanced website used to require programming knowledge and hours of coding.

menu

menu