Inclusive Design For Accessible Presentations

Original Source: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2018/11/inclusive-design-accessible-presentations/

Inclusive Design For Accessible Presentations

Inclusive Design For Accessible Presentations

Allison Ravenhall

2018-11-15T13:45:14+01:00

2018-11-15T17:08:15+00:00

To all the presenters of conferences, workshops, and meetups: I truly enjoy hearing your anecdotes and learning things from you. I like laughing at your jokes, especially the puns. Unfortunately, some people in your audience aren’t getting as much out of your session as me. They may not be able to see your slides, or hear you speak, or make out the details on the screen.

A few tweaks will make your presentation more inclusive. Here are some tips so next time you’re on stage, everyone in the crowd can laugh at your bad jokes.

1. Create Accessible Slides

Make Your Text Big. No, Bigger.

The back row of your presentation room is a long way from the projector screen. It’s much further than the distance between you and your laptop screen as you create your slides.

Small text in the middle of a large slide. (Large preview)

People up the back will appreciate every extra pixel you add to your font size. People with vision impairments will appreciate the larger text too — they’ve got a better chance of being able to read it.

Go big or go home. This goes for all text, even “less important” stuff like data labels, graph axes and legends, image captions, footnotes, URLs, and references.

Web forms are such an important part of the web, but we design them poorly all the time. The brand new Form Design Patterns book is our new practical guide for people who design, prototype and build all sorts of forms for digital services, products and websites. The eBook is free for Smashing Members.

Check the table of contents ↬

Is Your Slide Font Readable?

I love fonts; they can really set the tone of a talk. However, before you jump into the craziest corners of Google Fonts, think of your audience members with reading difficulties. Using handwriting or script fonts, particularly ones whose letters link together, makes text much harder to read. Using uppercase reduces scannability by removing ascenders and descenders, as well as being shouty.

There’s more scope to experiment with fonts on slides than web pages due to the larger text size, but here are some best practices:

Sans serif is typically the most readable.

Be generous with spacing (between letters, words, and lines).

Use bold for emphasis — underline and italic change the letter shapes, making them less identifiable.

Use mixed case, not all caps.

(Reference: British Dyslexia Association Style Guide 2018)

Does It Make Sense In Greyscale?

Do a print preview of your slides in black and white. Does it all still make sense without the color? If you send out your slides post-talk, some people may not have access to a color printer.

There’s also a good chance that someone at your talk is color-blind. If you’ve used red text for negative items and green text for positive items mixed together in a single list, they may not be able to tell them apart. If the datasets in your graphs only use color to differentiate, think about using patterns or labels to tell each bar, line or pie segment apart.

Don’t rely on color only to tell your story — enhance color with labels, icons, or other visual markers.

Recommended reading: Getting Started In Public Speaking

It’s A Slide, Not A Novel

Every time a new slide goes up, you lose the crowd while they scan the new content. If the slide is full of text, it’s going to take a long time for their attention to come back to what you’re saying.

People with attention deficiencies will struggle to read your slides and listen to what you’re saying at the same time. Audience members with reading difficulties may not finish reading text-heavy slides before you move on, and never mind what you said while they were concentrating on the screen.

Slides aren’t speaker notes. If you need prompts, write up some cards or use your slide program’s notes function. Use keywords and short phrases in your slides, not whole sentences or paragraphs, to share the essential ideas of your talk. Write and refer to a long-form companion piece if you want to share loads of detail that doesn’t translate well to slides.

Animated Slide Transitions? Really?

My high-school self-loved slide transitions — the zanier, the better. Look, my slide is swirling down a plughole! It’s swinging back and forth like a leaf on the breeze! Fades, swipes, shutters, I was all for it.

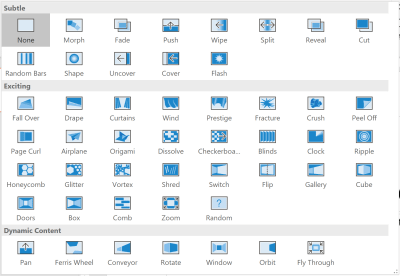

Microsoft PowerPoint contains 48 (!) animated slide transition options. (Large preview)

I have since discovered that slide transitions are overrated. More seriously, they can make the audience feel sick. Slide transitions and other animation such as parallax scrolling can trigger nausea, headaches and dizziness in people with vestibular (inner ear) disorders.

Make your audience groan with your punny jokes, not because they feel ill.

Readability Applies To Slide Text, Too

If you’re presenting, you probably know a decent amount about your topic. You likely use specialist words and phrases and assume a minimum level of audience knowledge.

Be mindful of using jargon and acronyms, even if you think they’re well-known. Explain them, don’t assume everyone knows them. Better still, use plain language for everything.

Don’t mistake using simpler words and shorter phrases for “dumbing it down”. Slides are for clear and concise ideas, not showing off your vocabulary. Save your fancy words for your next crossword puzzle.

GIFs Aren’t Always Funny

Animated GIFs are used in lots of presentations — usually as a killer quip or a laugh out loud punchline. They’re an easy way to add fun to dry tech talks but use with care — and I’m not talking about your bad sense of humor.

If the GIF content strobes or flashes rapidly, it may trigger seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy. It’s happened: in 2016, disgruntled Trump supporters caused a Newsweek writer with epilepsy to have a seizure by deliberately tweeting flashing images to him.

While a GIF is looping on the screen, I’m half-listening to the presenter at best. It’s so distracting. If there’s an animation on screen while you relate an anecdote, I’m going to miss the story.

When you create an animated GIF, you can configure the number of times it loops. This is a good compromise — have some fun with your audience, then they can focus on what you’re saying without distraction.

How Good Is Your Color Contrast?

The word ‘Binary’ on the bottom-left of this slide is presented in a large, readable font, but the color contrast is very poor. (Large preview)

There are recommended color contrast values for text on the web. The idea is to ensure text is visible even if you have a vision impairment or color-blindness.

Color contrast is important for slide content too. You probably won’t have much control over the environment, so it’s a good idea to use color combinations that go beyond recommended contrast ratios. I guarantee it won’t look as clear on the projector as it does on your computer.

Don’t be subtle with your color palette. Use bold colors that make your text stand out clearly from the background. Be careful about laying text over images — do it, just make sure the contrast is good. Use a color contrast checker and aim for a ratio of at least 4.5 : 1.

(Before you flame me about the big text minimum ratio being 3 : 1 for WCAG 2.0 AA, I figure it’s big up close, but it’s smaller from the audience’s perspective. They’re not likely to complain that it’s too high contrast, are they?)

Downloadable color contrast checker by the Paciello Group (for Windows & Mac)

Online color contrast checker by Lea Verou

If you know the setup in advance, light-colored text on a dark background is more audience-friendly in a darkened room; a white background can be dazzling. Some people have even resorted to wearing sunglasses when they were blinded by too much glare!

Enable Your Audience To Follow Along

If you plan to share your slides or you have complementary materials, include links to these on your first slide, and mention it in your intro. This enables your audience to follow along or adapt the presentation on their own devices. People with low vision can zoom in on visual content, and blind audience members can follow along on Braille displays or with a screen reader and earbuds.

Keep Your Links Short

If there’s a web link in your slide, there are two reasons to keep it as short as possible:

Readability: Long URLs will wrap onto multiple lines, which is hard to read.

Say-ability: You should say your URL out loud for people who can’t see the screen. A long URL is very hard to say correctly, particularly if it contains strings of random characters. It’s also very hard for listeners to understand and record in real time.

Use a URL shortener to create short links that point to the destination. If you can, maximize readability by customizing the short link to contain related word or two rather than a random string.

Does Your Presentation Contain Multimedia?

Video and audio clips are a great way of presenting events, interviews, and edited content that doesn’t work in real time.

If you’re playing video, think about audience members who can’t see the screen — is the audio descriptive enough by itself? Can a blind or low-vision person get a sense of what’s going on, or who’s speaking, purely from the soundtrack? You may need to introduce or summarise the vision yourself to add context.

If your video has an audio track or you’re playing a separate sound clip, are the visuals enough for someone who is deaf or hard of hearing? You should provide captions of decent size and contrast. Given an audio clip doesn’t have a visual component, you could display equivalent text or graphics while the audio is playing.

Don’t Put The Punchline At The Bottom Of Your Slide

This is more of a general usability tip. Don’t bottom-align slide text unless you know that the bottom of the screen is located well above the audience, or the audience seating is tiered. If the bottom of the projector screen is at or below the audiences’ head-height, and the floor is flat, people seated beyond the first few rows will likely not see what you wrote at the bottom of the slide.

Recommended reading: How To Transform Your Next Conference Takeaways Into Real-Life Results

2. Presenting Tips

Have A Clear Beginning, Middle, And End

It can be tempting to structure your talk towards a big reveal. This is a great device for building interest, but you run the risk of losing people with attention deficit disorders. More generally, if you find yourself running out of time, you may have to rush or cut short your final grand flourish!

Set expectations upfront. Start with a quick “Today I’ll be covering…” statement. You don’t have to give the whole game away, just tantalize the crowd with an outline. They can then decide if they want to commit their brain power to focus on your talk. Let the audience know that it’s OK for them to go if they wish.

Don’t be offended if someone chooses not to stay. They may have a limited capacity for focused thought each day, so a conference of back-to-back presentations and loud breakout spaces is challenging. They must pick and choose what is most useful to them. Hopefully, they’ll come back to your talk if it’s shared later.

Give The Audience Time To Read Your Slides

Complex content like graphs with multiple datasets take time to read and understand. If your slide is a slab of text, your audience will get annoyed if you summarise it and skip onto the next topic before they’ve finished reading.

Consider how much time your audience needs to read and understand each slide, based on the amount and complexity of the content. Remember, they’re seeing it for the first time, and they don’t know as much about the topic as you. Structure your talk so complex slides stay up on the screen long enough to be read completely.

You worked hard on those slides, it’d be a shame if they weren’t appreciated!

Provide Captions And Foreign Language Translation

I’ve attended events that have provided sign language interpreters or live captions to translate or transcribe what the speakers say in real time. They’re invaluable for people who are deaf or hard of hearing. International events may also provide foreign-language translation.

If you present at an event that provides these services, send your slides or speaker notes to the interpreters and captioners in advance. They can then research and practice unfamiliar terms before the day.

Many events don’t provide captioning or translation. They’re beyond the budget of most conferences, being both specialized and labor-intensive. In this case, you can potentially provide your own captions.

MS PowerPoint has a free Presentation Translator plug-in to add real-time captions and foreign language translation. I saw a demo at A11y Camp Sydney last year:

A live demo of @Microsoft Translate as transcript by @mastersofdavid at #A11yCampSyd pic.twitter.com/DW3K4J7wfH

— Allison Ravenhall (@RavenAlly) September 13, 2017

Google recently added real-time captioning to its Slides product, too.

Mind Your Language

Your choice of words may be offending or excluding some of your audience, and you may not even know you’re doing it.

Not all people that work in technology are “guys.” When a speaker says “I talked to the guys about it,” I imagine a group of men. If they’d said “I talked to the developers about it,” then my imaginary group also contains women.

There’s also ableist language. Using words like retarded, insane, lame, and crazy incorrectly is degrading to those with mental and physical disorders. What’s a normal user? Are you making assumptions about gender, sexual orientation, race, family unit, technical knowledge, physical or mental abilities, or level of education?

Then there’s swearing, commonly used to get attention or add some spice. Be careful about deploying this weapon. If you’ve misjudged the room, you could put people offside. If you’re traveling, that fairly tame curse word you use at home could be deeply offensive elsewhere.

Stories Aren’t Universal

When I discussed color contrast at A11y Bytes 2017, I moaned about not being able to see my phone screen in bright sunlight. Attempting to relate, I asked “we’ve all been there, right?”, expecting a few nods and smiles.

The retort was lightning-fast: “Can’t say I’ve found it a problem!” Laughter rippled through the crowd as I realized I’d just been heckled by a blind woman. She graciously laughed off my hasty apology.

I still tell my sunlight story, but now I’m mindful that not everyone can relate to it directly. Learn from my mistake, don’t assume your audience has the same abilities and experiences as you.

Interests And Pop Culture References Aren’t Universal Either

My most recent presentations have been about WCAG 2.1, including the need to provide alternatives to motion-based inputs. I use three Nintendo Switch games as examples.

I don’t assume that the audience has used a Switch. I briefly explain the premise of each game and the motion input it uses before I move on to how it relates to the new success criteria. It’s a courtesy to those people who don’t share my interest in the Switch.

Similarly, much as I’d love to do a Star Wars-themed accessibility talk, I won’t because I’d be putting my own amusement ahead of informing my audience. Some people aren’t into Star Wars, just as I’m not a Trekkie or a Whovian. It’d be a shame for them to misunderstand me because they can’t translate my tenuous Star Wars associations — or worse — if they saw the themed talk title and skipped my session altogether.

Have some fun, by all means, include a pop culture reference or two, but don’t structure your entire talk around it. Make it work for someone who hasn’t watched that movie, or heard that band, or read that book, or seen that meme.

A Picture Is Worth A Thousand (Spoken) Words

Photos, graphics and drawings all add interest to your slides. You may have screenshots of a website you’ve built, or photos of people or places you’re talking about.

When your slide imagery is part of the story, remember to describe the pictures for those in the audience that can’t see it. Try not to say “As you can see here…” because someone may not be able to see there.

If you think it’s awkward to quickly rehash a sight gag, think how awkward you’d feel if you were in a room full of people that suddenly all laughed and you didn’t know why.

Slow Down, Breathe.

You’re nervous. You’ve never presented before. You’ve got a time limit and lots to share. You haven’t practiced. Your parents, friends, children, workmates, industry idols, and managers are all in the room.

Whatever the reason, you probably talk faster than usual when you present. This puts pressure on interpreters and captioners, particularly if your talk contains tech-speak. Your audience may struggle to keep up too. Note-takers mash their laptops in vain, live-tweeters’ thumbs cramp up, and sketchnoters leave a trail of half-drawn doodles in their wake. International visitors may get lost figuring out your accent. Cognitively, everyone is thinking furiously to keep up, and it’s hard work!

Practice. Slow down. No one knows your stuff as well as you; give everyone else time to take it in.

Respect The Code Of Conduct And Your Audience

Codes of conduct are found at most public speaking events, such as this one by UX Gatherings. They set the minimum behavior standard for speakers and attendees.

Read the code of conduct for every event you attend — they can differ broadly. Know the no-go zones and don’t go there.

If you are talking about sensitive topics that may upset some of your audience, give them plenty of notice so they can prepare or remove themselves from the discussion. A note in the event program, if possible. A mention on your lead slide, and during your opening remarks. Include contact details of support services if appropriate.

Make Your Code Demonstrations Accessible, Too

Well done if you have mastered the art of the live code demonstration. Few presenters can show off something meaningful that also works while providing a clear commentary.

You know what would take your code demo to the next level? Jacking up the font size. Your usual code editor font size is perfect when you’re sitting at your desk, but it’s not big enough for those sitting in the back row of your presentation.

Check your editor’s color settings too. A pure white background might be startlingly bright in a darkened room. Make sure your editor text colors have good contrast as well.

Don’t Drop The Mic

If there’s a microphone on offer, use it, even if it’s a small space.

Many public conference spaces have an audio induction (hearing) loop connected to their AV systems. The loop transmits the AV output directly to hearing aids and cochlear implants. People who are hard of hearing receive the target audio without background noise.

Recommended reading: Getting The Most Out Of Your Web Conference Experience

3. After The Presentation

Congratulations! You’ve done your talk. There are just a couple more things that’ll round this thing out nicely.

Distribute Accessible Slides

Lots of presenters publish their slides after the talk is done. If this is you, make them accessible! Correct semantics, meaningful read order, ALT text on images, enough color contrast, video captions, limited animation looping, reasonable slide transitions, all the good stuff.

Fill The Gaps With Notes, A Transcript Or An Article

Help people that need more time to take in your talk and need more detail than what’s on your slides. Publish your speaker notes or a companion piece that covers your topic(s). If the event is recorded, ask the organizers to include captions or a transcript (but perhaps don’t rely on YouTube’s auto-captioning).

Conclusion

Applying these tips will make a big difference to your whole audience. Your slide content, design, and how you present can all affect how well the crowd gets your message, if at all. This is particularly true for those with physical and cognitive conditions.

Making subtle changes to what you show and your script will help all attendees, not just those with disabilities, to get the most out of your hard work.

(ra, yk, il)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!