Creating Accessible UI Animations

Original Source: https://smashingmagazine.com/2023/11/creating-accessible-ui-animations/

Ever since I started practicing user interface design, I’ve always believed that animations are an added bonus for enhancing user experiences. After all, who hasn’t been captivated by interfaces created for state-of-the-art devices with their impressive effects, flips, parallax, glitter, and the like? It truly creates an enjoyable and immersive experience, don’t you think?

Mercado Libre is the leading e-commerce and fintech platform in Latin America, and we leverage animations to guide users through our products and provide real-time feedback. Plus, the animations add a touch of fun by creating an engaging interface that invites users to interact with our products.

Well-applied and controlled animations are capable of reducing cognitive load and delivering information progressively — even for complex flows that can sometimes become tedious — thereby improving the overall user experience. Yet, when we talk about caring for creating value for our users, are we truly considering all of them?

After delving deeper into the topic of animations and seeking guidance from our Digital Accessibility team, my team and I have come to realize that animations may not always be a pleasant experience for everyone. For many, animations can generate uncomfortable experiences, especially when used excessively. For certain other individuals, including those with attention disorders, animations can pose an additional challenge by hindering their ability to focus on the content. Furthermore, for those afflicted by more severe conditions, such as those related to balance, any form of motion can trigger physical discomfort manifested as nausea, dizziness, and headaches.

These reactions, known as vestibular disorders, are a result of damage, injury, or illnesses in the inner ear, which is responsible for processing all sensory information related to balance control and eye movements.

In more extreme cases, individuals with photosensitive epilepsy may experience seizures in response to certain types of visual stimuli. If you’d like to learn more about motion sensitivity, the following links are a nice place to start:

“Designing Safer Web Animation For Motion Sensitivity,” Val Head

“Accessibility for Vestibular Disorders,” Facundo Corradini

“Animation for Attention and Comprehension,” Aurora Harley

Animation and motion (web.dev)

How is it possible to strike a balance between motion sensitivities and our goal of using animation to enhance the user interface? That is what our team wanted to figure out, and I thought I’d share how we approached the challenge. So, in this article, we will explore how my team tackles UI animations that are inclusive and considerate of all users.

We Started With Research And Analysis

When we realized that some of our animations might cause annoyance or discomfort to users, we were faced with our first challenge: Should we keep the animations or remove them altogether? If we remove them, how will we provide feedback to our users? And how will not having animations impact how users understand our products?

We tackled this in several steps:

We organized collaborative sessions with our Digital Accessibility team to gain insights.

We conducted in-depth research on the topic to learn from the experiences and lessons of other teams that have faced similar challenges.

Note: If you’re unfamiliar with the Mercado Libre Accessibility Team’s work, I encourage you to read about some of the things they do over at the Mercado Libre blog.

We walked away with two specific lessons to keep in mind as we considered more accessible UI animations.

Lesson 1: Animation ≠ Motion

During our research, we discovered an important distinction: Animation is not the same as motion. While all moving elements are animations, not every animated element necessarily involves a motion as far as a change in position.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) include three criteria related to motion in interfaces:

Pause, stop, and hide

According to Success Criterion 2.2.2 (Level AA), we ought to allow users to pause, stop, or hide any content that moves, flashes, or scrolls, as well as those that start or update automatically or that last longer than five seconds and is presented in parallel with other content.

Moving or flashing elements

Success Criterion 2.3 includes guidelines for avoiding seizures and negative physical reactions, including 2.3.1 (Level A) and 2.3.2 (Level AAA) for avoiding intermittent animations that flash more than three times per second as they could trigger seizures.

Animation from interactions

Success Criterion 2.3.3 specifies that users should be able to interact with the UI without solely relying on animations. In other words, the user should be able to stop any type of movement unless the animation is essential for functionality or conveying information.

These are principles that we knew we could lean on while figuring out the best approach for using animations in our work.

Lesson 2: Rely On Reduced Motion Preferences

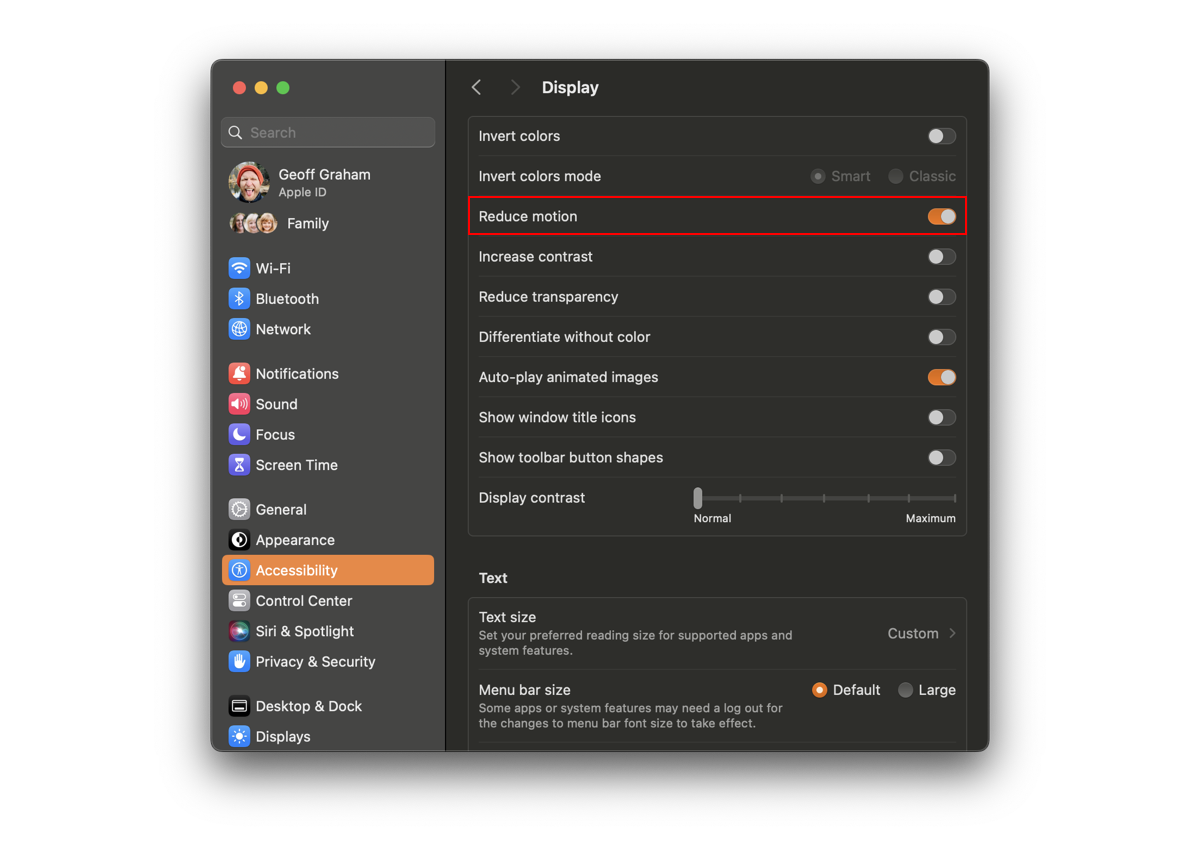

Our Digital Accessibility team made sure we are aware of the prefers-reduced-motion media query and how it can be used to prevent or limit motion. MacOS, for example, provides a “Reduce motion” setting in the System Settings.

As long as that setting is enabled and the browser supports it, we can use prefers-reduced-motion to configure animations in a way that respects that preference.

:root {

–animation-duration: 250ms;

}

@media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce), (update: slow) {

/* Increase duration to slow animation when a user requests a reduced animation experience */

.animated {

–animation-duration: 0 !important;

}

}

Eric Bailey is quick to remind us that reduced motion is not the same as no motion. There are cases where removing animation will prevent the user’s understanding of the content it supports. In these cases, it may be more effective to slow things down rather than remove them completely.

:root {

–animation-duration: 250ms;

}

@media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce), (update: slow) {

/* Increase duration to slow animation when reduced animation is preferred */

* {

–animation-duration: 6000ms !important;

}

}

Armed with a better understanding that animation doesn’t always mean changing positions and that we have a way to respect a user’s motion preferences, we felt empowered to move to the next phase of our work.

We Defined An Action Plan

When faced with the challenge of integrating reduced motion preferences without significantly impacting our product development and UX teams, we posed a crucial question to ourselves: How can we effectively achieve this without compromising the quality of our products?

We are well aware that implementing broad changes to a design system is not an easy task, as it subsequently affects all Mercado Libre products. It requires strategic and careful planning. That said, we also embrace a mindset of beta and continuous improvement. After all, how can you improve a product daily without facing new challenges and seeking innovative solutions?

With this perspective in mind, we devised an action plan with clear criteria and actionable steps. Our goal is to seamlessly integrate reduced motion preferences into our products and contribute to the well-being of all our users.

Taking into account the criteria established by the WCAG and the distinction between animation and motion, we classified animations into three distinct groups:

Animations that do not apply to the criteria;

Non-essential animations that can be removed;

Essential animations that can be adapted.

Let me walk you through those in more detail.

1. Animations That Do Not Meet The Criteria

We identified animations that do not involve any type of motion and, therefore, do not require any adjustments as they did not pose any triggers for users with vestibular disorders or reduced motion preferences.

Animations in this first group include:

Objects that instantly appear and disappear without transitions;

Elements that transition color or opacity, such as changes in state.

A button that changes color on hover is an example of an animation included in this group.

Button changing color on mouse hover. (Large preview)

Button changing color on mouse hover. (Large preview)

As long as we are not applying some sort of radical change on a hover effect like this — and the colors provide enough contrast for the button label to be legible — we can safely assume that it is not subject to accessibility guidelines.

2. Unessential Animations That Can Be Removed

Next, we categorized animations with motions that were unessential for the interface and contrasted them with those that did add context or help navigate the user. We consider unessential animations to be those that are not crucial for understanding the content or state of the interface and that could cause discomfort or distress to some individuals.

This is how we defined animations that are included in this second group:

Animated objects that take up more than one-third of the screen or move across a significant distance;

Elements with autoplay or automatic updates;

Parallax effects, multidirectional movements, or movements along the Z-axis, such as changes in perspective;

Content with flashes or looping animations;

Elements with vortex, scaling, zooming, or blurring effects;

Animated illustrations, such as morphing SVG shapes.

These are the animations we decided to completely remove when a user has enabled reduced motion preferences since they do not affect the delivery of the content, opting instead for a more accessible and comfortable experience.

Some of this is subjective and takes judgment. There were a few articles and resources that helped us define the scope for this group of animations, and if you’re curious, you can refer to them in the following links:

“How to Make Motion Design Accessible,” Alik Brundrett

“Designing With Reduced Motion For Motion Sensitivities,” Val Head

“Responsive Design for Motion,” James Craig

For objects that take up more than one-third of the screen or move position across a significant distance, we opted for instant transitions over smooth ones to minimize unnecessary movements. This way, we ensure that crucial information is conveyed to users without causing any discomfort yet still provide an engaging experience in either case.

Comparing a feedback screen with animations that take up more than one-third of the screen versus the same screen with instant animations. (Large preview)

Comparing a feedback screen with animations that take up more than one-third of the screen versus the same screen with instant animations. (Large preview)

Other examples of animations we completely remove include elements that autoplay, auto-update, or loop infinitely. This might be a video or, more likely, a carousel that transitions between panels. Whatever the case, the purpose of removing movement from animations that are “on” by default is that it helps us conform to WCAG Success Criterion 2.2.2 (Level AA) because we give the user absolute control to decide when a transition occurs, such as navigating between carousel panels.

Additionally, we decided to eliminate the horizontal sliding effect from each transition, opting instead for instantaneous changes that do not contribute to additional movement, further preventing the possibility of triggering vestibular disorders.

Comparing an auto-playing carousel with another carousel that incorporates instant changes instead of smooth transitions. (Large preview)

Comparing an auto-playing carousel with another carousel that incorporates instant changes instead of smooth transitions. (Large preview)

Along these same lines, we decided that parallax effects and any multidirectional movements that involve scaling, zooming, blurring, and vortex effects are also included in this second group of animations that ought to be replaced with instant transitions.

Comparing a card flip animation with smooth transitions with one that transitions instantly. (Large preview)

Comparing a card flip animation with smooth transitions with one that transitions instantly. (Large preview)

The last type of animation that falls in this category is animated illustrations. Rather than allowing them to change shape as they normally would, we merely display a static version. This way, the image still provides context for users to understand the content without the need for additional movement.

Comparing an animated illustration with the same illustration without motion. (Large preview)

Comparing an animated illustration with the same illustration without motion. (Large preview)

3. Essential Animations That Can Be Adapted

The third and final category of animations includes ones that are absolutely essential to use and understand the user interface. This could potentially be the trickiest of them all because there’s a delicate balance to strike between essential animation and maintaining an accessible experience.

That is why we opted to provide alternative animations when the user prefers reduced motion. In many of these cases, it’s merely a matter of adjusting or reducing the animation so that users are still able to understand what is happening on the screen at all times, but without the intensity of the default configuration.

The best way we’ve found to do this is by adjusting the animation in a way that makes it more subtle. For example, adjusting the animation’s duration so that it plays longer and slower is one way to meet the challenge.

The loading indicator in our design system is a perfect case study. Is this animation absolutely necessary? It is, without a doubt, as it gives the user feedback on the interface’s activity. If it were to stop without the interface rendering updates, then the user might interpret it as a page error.

Rather than completely removing the animation, we picked it apart to identify what aspects could pose issues:

It could rotate considerably fast.

It constantly changes scale.

It runs in an infinite loop until it vanishes.

The loading indicator. (Large preview)

The loading indicator. (Large preview)

Considering the animation’s importance in this context, we proposed an adaptation of it that meets these requirements:

Reduce the rotation speed.

Eliminate the scaling effect.

Set the maximum duration to five seconds.

Comparing the loading indicator with and without reduced motion preferences enabled. (Large preview)

Comparing the loading indicator with and without reduced motion preferences enabled. (Large preview)

The bottom line:

Animation can be necessary and still mindful of reduced motion preferences at the same time.

This is the third and final category we defined to help us guide our decisions when incorporating animation in the user interface, and with this guidance, we were able to tackle the third and final phase of our work.

We Expanded It Across All Our Products

After gaining a clear understanding of the necessary steps in our execution strategy, we decided to begin integrating the reduced motion preferences we defined in our design system across all our product interfaces. Anyone who manages or maintains a design system knows the challenges that come with it, particularly when it comes to implementing changes organically without placing additional burden on our product teams.

Our approach was rooted in education.

Initially, we focused on documenting the design system, creating a centralized and easily accessible resource that offered comprehensive information on accessibility for animations. Our focus was on educating and fostering empathy among all our teams regarding the significance of reduced motion preferences. We delved into the criteria related to motion, how to achieve it, and, most importantly, explaining how our users benefit from it.

We also addressed technical aspects, such as when the design system automatically adapts to these preferences and when the onus shifts to the product teams to tailor their experiences while proposing and implementing animations in their projects. Subsequently, we initiated a training and awareness campaign, commencing with a series of company-wide presentations and the creation of accessibility articles like the one you’re reading now!

Conclusion

Our design system is the ideal platform to apply global features and promote a culture of teamwork and consistency in experiences, especially when it comes to accessibility. Don’t you agree?

We are now actively working to ensure that whenever our products detect the default motion settings on our users’ devices, they automatically adapt to their needs, thus providing enhanced value in their experiences.

How about you? Are you adding value to the user experience of your interfaces with accessible animation? If so, what principles or best practices are you using to guide your decisions, and how is it working for you? Please share in the comments so we can compare notes.